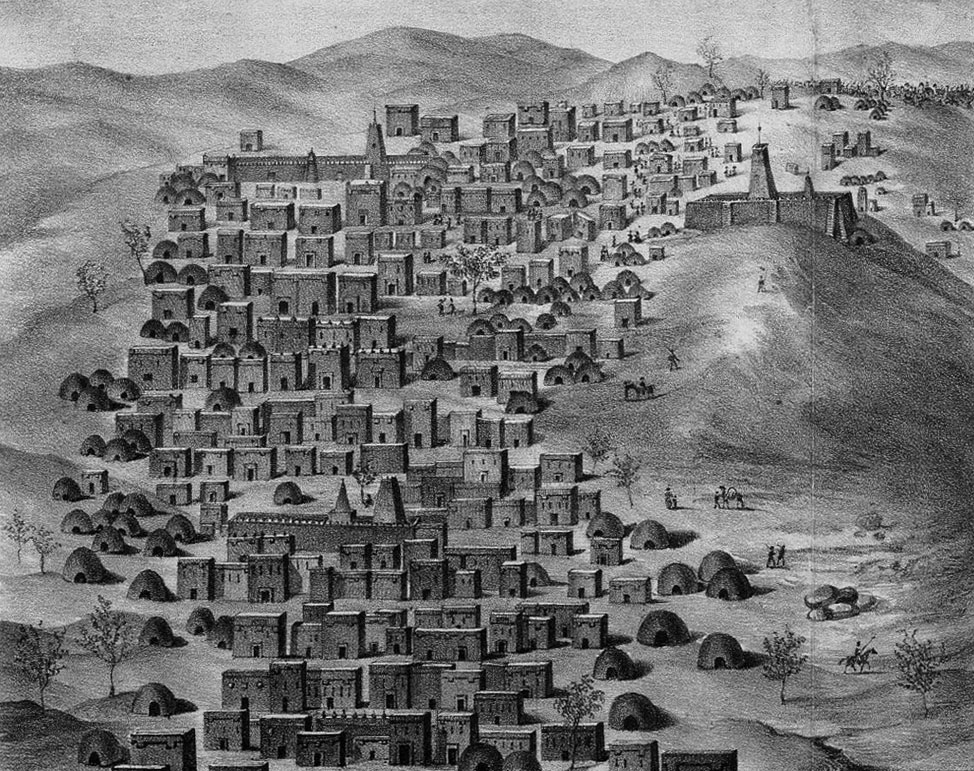

In 1324, Musa Keita I, the mansa (king or sultan) of the Malian empire, set out upon the Hajj—the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca. Along the way, he gave gold to the poor—so much gold, in fact, that he devalued the metal, as prices for all things increased. This display of wealth contributed to the legend of his capital, Timbuktu.

Word of Timbuktu filtered slowly to Europeans through Islamic sources, and by the time European explorers were mapping the world and dividing it up for their colonial empires, the city had, in the European imagination, become a byword for the distant and fantastic. In truth, its power and wealth had declined. Located in the heart of Sub-Saharan Africa, near the Niger River (which had itself never been mapped by Europeans), Timbuktu was accessible either across the Sahara, through lands controlled by Muslims hostile to Christian Europeans, or through the tropical jungles of West Africa. Starting in the 17th century, European expeditions had set out in search of the fabled city, but expedition after expedition failed, and many or most did not return.

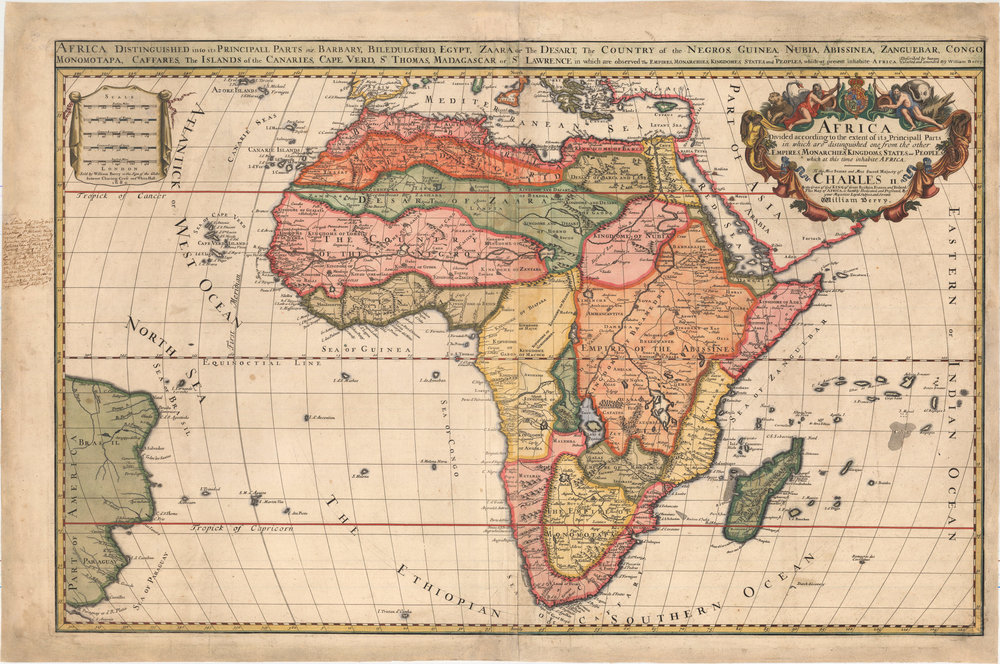

In this map by William Berry published in London in 1680, we see only a generalized Kingdome of Tombut with a stylized representation of the city of Tombut situated on the Niger River.

In the early 19th century, an American sailor claimed to have been to Timbuktu after being shipwrecked and enslaved, but his account of a poor, dull, and dirty city was not believed.

In August of 1826, a British explorer, Alexander Gordon Laing, sent a letter from Timbuktu, having become the first European to cross the Sahara from north to south. Laing’s journey had taken 13 months of great hardship—including the loss of his right hand to Tuareg raiders. In September, shortly after setting out north to recross the Sahara, Laing was killed, and his papers never recovered.

Two years later, a Frenchman, René Caillé, arrived in Timbuktu, having made the journey in disguise as an Egyptian Muslim who had been raised in France. On his return, Caillé was able to claim the prize offered by Geographical Society of Paris for the first person to reach the city. Like the American sailor, Caillé reported that Timbuktu was small and poor. The myth of the city of vast wealth was dispelled, and it would be a quarter century before another European would set foot there.