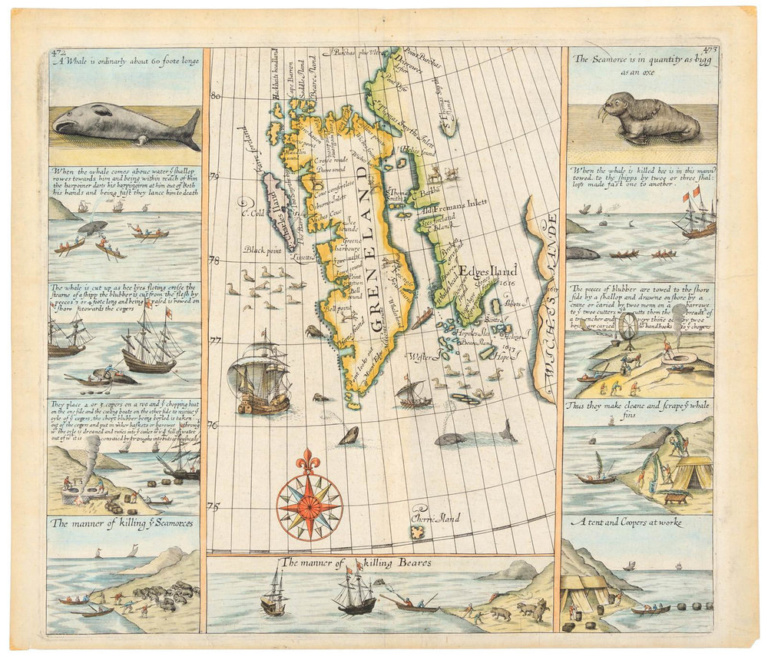

By the middle of the 18th century, European explorers had visited and mapped most of the world, and yet there was unknown terrain close to home. Mountaineering, which is now a pastime leisure activity, was unknown, and the residents of high-elevation terrain (in Europe, at least), did not venture into the heights that surrounded their homes.

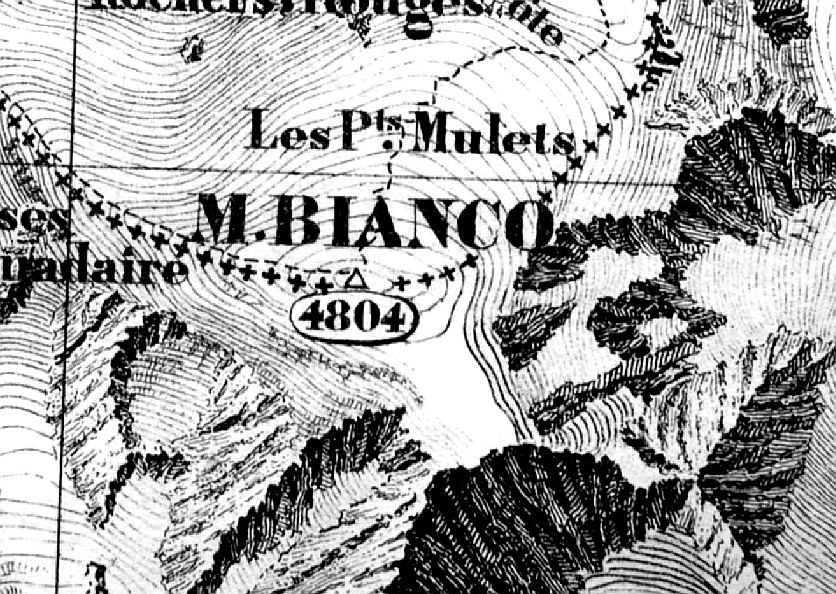

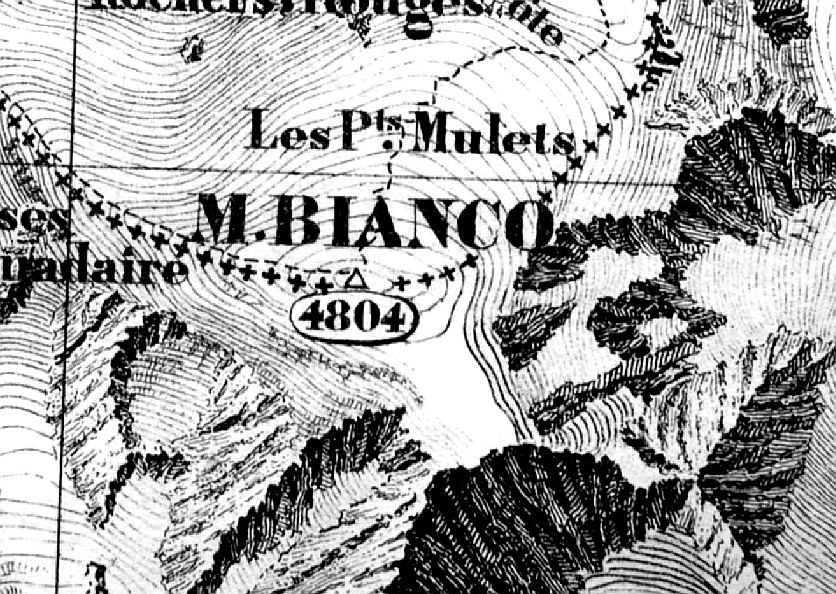

Mont Blanc, for example, the highest of the Alps, had never been climbed and there was doubt that humans could survive the thin air. It was a distant, dangerous world, and yet also right there in plain sight. In the present day, Mont Blanc is actually considered a relatively simple climb, little more than a strenuous hike. Compared to the famed alpine challenges of the Matterhorn or the north face of the Eiger, Mont Blanc is a mountain for amateurs or children—literally: the youngest person to reach the summit was 10 years old.

But in the 18th century, the mountain had never been climbed.

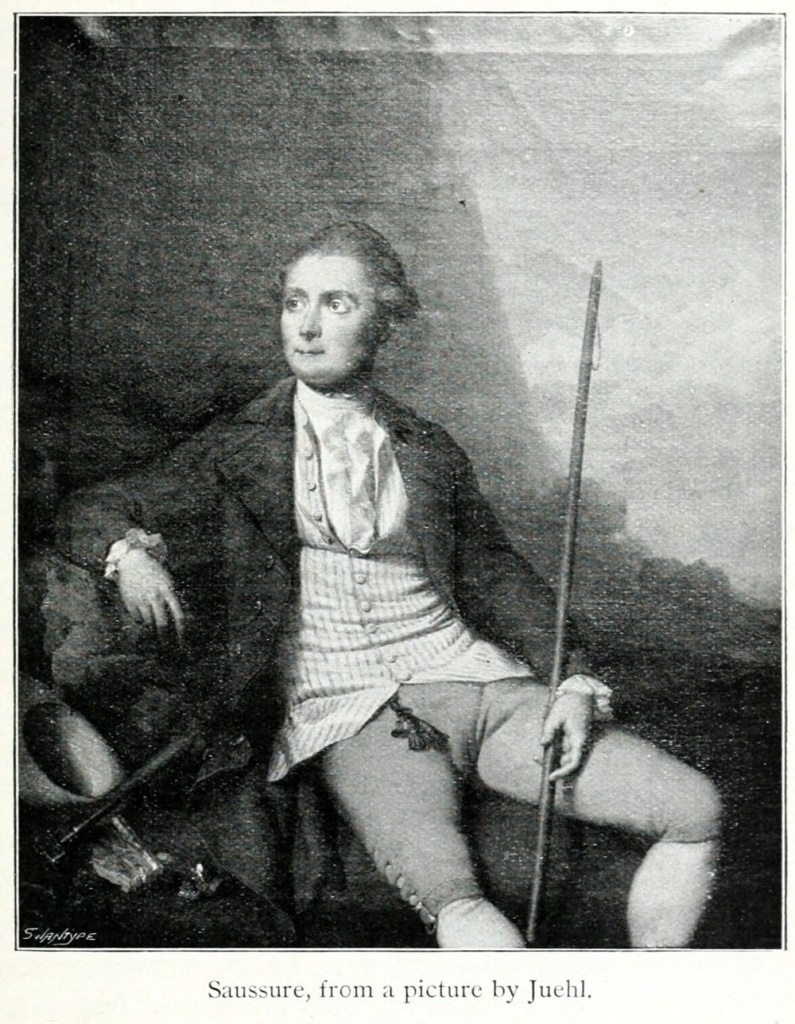

Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, a resident of Geneva, was fascinated with the mountains and with Mont Blanc. As a young man, he visited the town of Chamonix and was inspired to offer a reward for a successful ascent of the peak. He also offered to pay the costs of failed attempts. Nonetheless, it would be over 25 years before the reward was claimed in 1786.

When it finally was claimed, Saussure was not satisfied. The mountain had been climbed, but Saussure wanted more than just the ascent: he wanted scientific data that could only be collected at (or near) the summit, and as a result, Saussure himself would lead an expedition that would make an ascent the year after the mountain was first summited, and would remain near the peak for two weeks.

Saussure’s journals and expedition became famous, and their glowing descriptions of the alpine peak are now viewed as the spark that inspired the new sport/recreation of alpine mountaineering in 19th century Europe.

“The soul is uplifted,” he wrote, “the powers of the intelligence seem to widen and in the midst of this majestic silence, one seems to hear the voice of Nature and to become the confidant of her most secret workings.”

By the time Saussure’s fascination with Mont Blanc inspired mountaineering, Europeans had been sailing around the world for centuries, mapping and exploring much of the inhabited world. Icy wildernesses remained, but one of those—the Alps—the wilderness close to home—were soon to become familiar terrain.