The earliest obtainable map of Italy, a gorgeous impression in original black & white.

Sexta Europe. Tabula.

Out of stock

Description

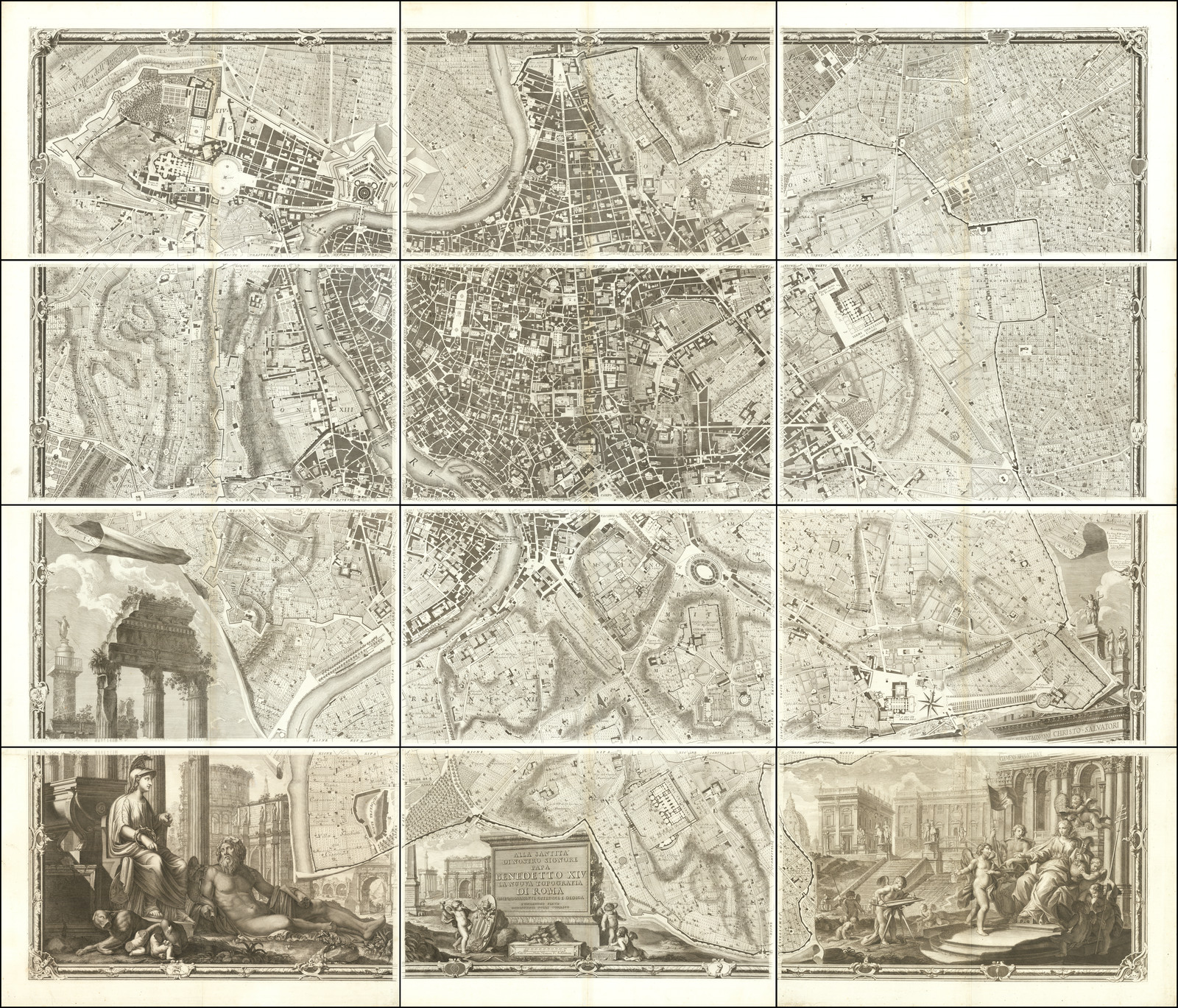

This remarkable late 15th-century map of Italy is the original sixth plate in the 1478 or 1490 Rome edition of Ptolemy. Like all maps published in the 15th century, it is extremely rare and highly collectible. The atlas in which it appeared was among the first Ptolemaic atlases in history to include visualizations in the form of maps. The current sheet consequently reigns among the earliest printed maps of Italy in history.

Ptolemaic maps of the 15th century

While translations of Ptolemy’s Geographia into Greek and Latin had been around for more than a century when this map was published, only in 1477 did the first printed version with maps appear in Bologna. The following year, a similar edition was printed in Rome, although many of the maps looked distinctly different. Most scholars agree that the maps of the 1478 Rome edition were probably compiled before those of the Bologna. However, the compilation and printing of the Bologna edition was a faster process. Regardless of which came first, the same small circle of men apparently engraved both sets of maps.

Among the known mapmakers were two Germans, Conrad Sweynheym and Arnold Pannartz, who had trained with Gutenberg himself and who were responsible for bringing printing press technology to Italy. Sweynheym also developed a printing method for finely engraved copper plates, and he seems to have been behind most of the Bologna and Rome editions’ maps. However, Sweynheym died a year before the Bologna edition was published. So the printer of the first Rome edition, Arnold Buckinck, is presumed to have finished the plates started by Sweynheym himself.

In 1490, these plates were purchased by the Spanish printer Petrus de Turre (Pedro de la Torre), who quickly used them to publish a second edition of the Rome Ptolemy using the same plates. It is from this edition that our sheet comes.

Between the publication of the original Rome edition and the second edition by de Turre, two other important Ptolemaic atlases were produced, both in 1482. The Italian Francesco Niccolo Berlinghieri compiled a work that was not a Ptolemaic atlas in the traditional sense but rather a description of the world in Italian verse supported with Ptolemaic style maps. The other was the so-called Ulm Edition of Ptolemy, the first printed atlas to be produced outside Italy.

Sextus Europe Tabula: The primordial rendering of Renaissance Italy

Like most Ptolemaic maps from the late 15th and 16th centuries, the maps of the Rome edition were presented as so-called tabulas, each depicting a specific part of the world. As the title indicates, the Italy map constitutes the sixth European table in the Rome atlas and the seventh map overall.

The double plate folio map includes the entire Italian Peninsula from the Alps to Sicily. In addition to Italy and Corsica, parts of the Adriatic coastline, Sicily, and Corsica are also visible. The map’s focus is nevertheless made evident in its design, which fills the subject matter with a dense cornucopia of detail, but leaves adjacent lands completely blank. Mountain ranges, lakes, rivers, and towns are all illustrated, just as regional subdivisions and toponyms are printed in what little available space remains. Among its most particular characteristics is the drooping heel of Salento, which tilts westwards. Interestingly, this strange configuration was uncritically adopted in the Ulm edition. In contrast, the more independent Belinghieri shows an entirely different and, in many ways, more accurate model in which the Salento Peninsula points almost directly east.

Identifying and dating maps from the Rome edition

As noted, four distinct editions of the Rome Cosmographia were issued, but the bulk of the maps was printed from the same plates as the original 1478 edition. Consequently, it can be difficult, if not impossible, to identify from which edition a loose map might derive. We might as well state it outright: there is no way to know from which edition of the Rome Cosmographia our particular map comes.

Two principal clues aid scholars in dating separated Rome Ptolemy maps. The first, as mentioned above, are minor variations in the maps from edition to edition. Unfortunately, Prima Asiae Tabula has no variations in the four Rome editions. The second clue involves the paper’s watermark. Marcel Destombes (1952) was the first to seriously argue that individual sheets of the Rome editions could be identified by their watermark. Destombes also provided some initial analysis by attributing certain watermarks to specific editions, including a claim that a crossbow and lion denoted the 1478 edition. In contrast, a cardinal’s hat, a ladder, a French lily, or a T in a circle represented the 1490 edition.

More recent scholarship (Peerlings et al. 2017) has reinforced the idea that specific watermarks can be associated with certain editions. Still, they also note how – due in part to the printing procedure – many map sheets do not allow dating in this manner – at least not with any degree of certainty. Some maps, for example, have two contradicting watermarks, one in each half. In other cases, there is no watermark; this is the case for our map, which lacks a watermark.

Why would most Rome Ptolemy maps have one or two watermarks while others have none? We find the answer to this question in the printing methodology. Roughly half of the loose maps have two watermarks, whereas about a quarter have one, and about a quarter have none. Mathematically, this is explained by the procedure by which such maps were printed. We have already noted how these maps were printed as two halves and joined, with no text on the verso. In all likelihood, the reams of paper for printing would have required that each sheet was cut in half and subsequently printed using a single copperplate (i.e. half of a map). The printer completed each run before moving on to the next, seemingly indifferent to what sheet halves were used.

The consequence was a random mixture. Each large sheet of paper had one watermark but would become two sheets for printing. Later, the two halves were joined again to form the final map. If the printer did not concern himself with what half of a sheet was being used, or indeed what face or direction the paper turned when printing, statistically, the outcome would reflect what we have today. The procedure not only explains why we have sheets with no watermarks but also why there are sheets that have two. It even explains those rare cases where the two halves of a map contain different watermarks. Because the same plates were used in all four editions, half-sheets from different editions may have been joined in later composite atlases or simply from old inventory.

Skelton has argued that about 500 copies of the original 1478 edition were published, marking the smallest run of the four editions. Moreover, the variation of watermarks in the 1478 edition is the most limited, making their attribution easier as long as a watermark exists. In the case of no watermark, raw statistics suggest that 1478 is the least likely date for an unmarked map. However, even when no watermark exists, secondary indications can help one hone in on the date. The most critical element in this regard, which several scholars have noted, is that the 1478 and 1490 editions were printed on high-quality paper, which is certainly true of our map.

In light of the complex history behind this seminal work, Neatline cannot guarantee from which edition of the Rome Cosmographia our sheet derives. What we can say, however, is that it was printed from Sweynheym’s original plate without variations or amendments and that it belonged to one of the most important geographic publications in history.

Cartographer(s):

Roman geographer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 – 170 CE) solidified geography as an independent discipline.

The Ptolemaic understanding of the world stems from Ptolemy’s seminal work, Geographia. Initially intended to revise and critique another (now lost) geography written by Marinus of Tyre, Ptolemy compiled Geographia in Alexandria around 150 CE. It consisted of a treatise on world geography, instructions on making maps, and a topographically-anchored gazetteer. It forms the basis of scientific cartography: a coordinate-based system meant that future cartographers (even many centuries later) could recreate its maps using the published data. The work covered an area from the Canary Islands in the west to the coasts of China and Korea in the east.

Pietro de la TorrePietro de la Torre was a Spanish mapmaker, engraver, and printer living in Italy. He is most famous for acquiring the plates of the 1478 Rome edition of Ptolemy and issuing his own edition of the atlas in 1490.

Condition Description

Very good. Centerfold reinforced on verso with archival tape. Smudges in the margins.

References

![[Persia & Mesopotamia] Tabula Quinta de Asia.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NL-02006-NEWEST_thumbnail-300x300.jpg)