Francesco Berlinghieri and Niccolò Tedesco’s formative 1482 map of Sri Lanka.

[Sri Lanka] Tabula Duodecima Dasia.

$6,200

1 in stock

Description

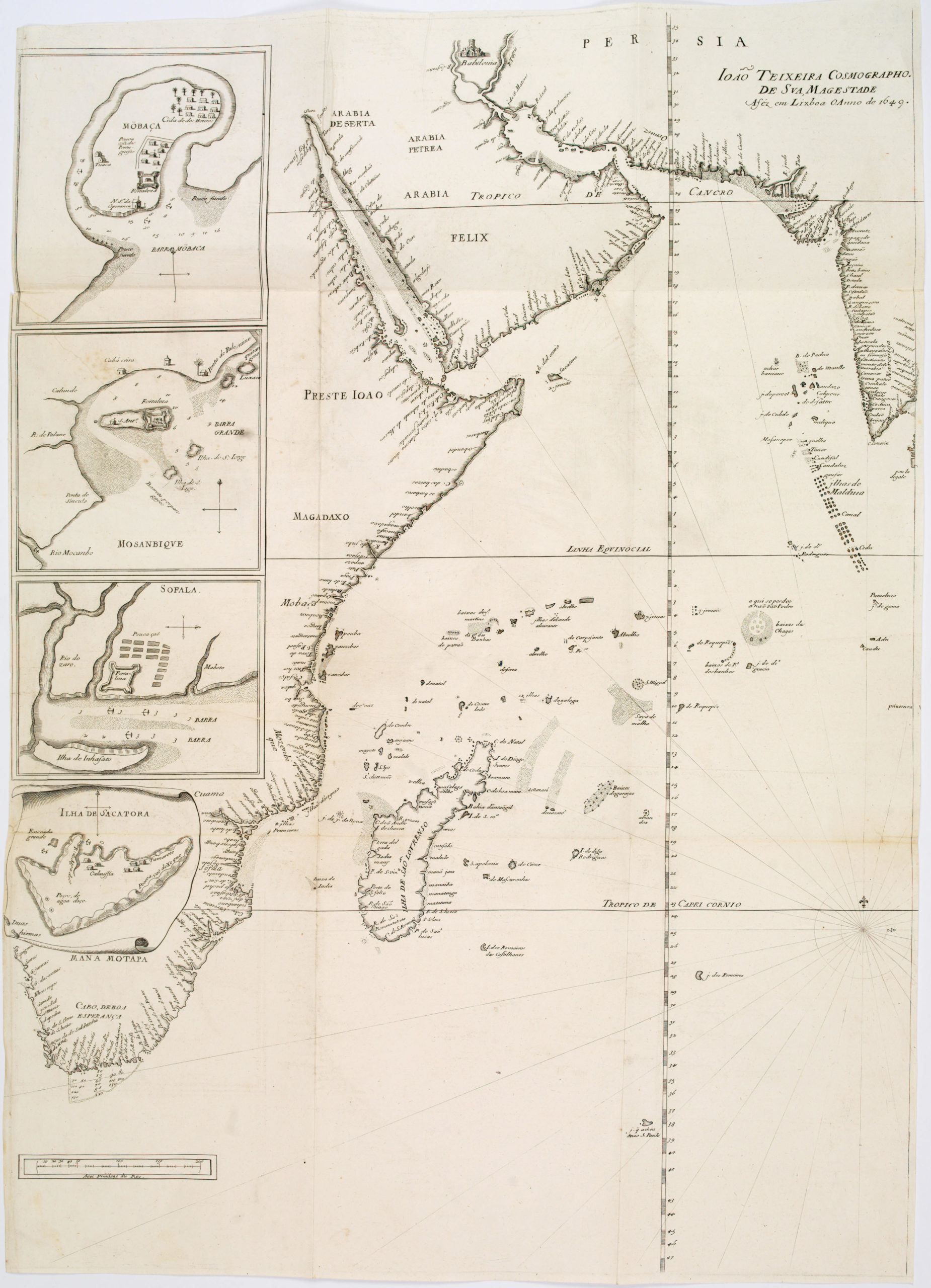

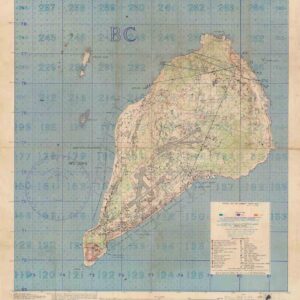

This is an extremely rare late 15th-century map of Sri Lanka, published a full six years before Portuguese navigator Bartolomeu Dias first rounded the Cape of Good Hope. Titled Tabula Duodecima Dasia, this Ptolemaic tavola-map is one of the earliest dedicated maps of Sri Lanka available on the market and one of the earliest printed maps of this region in existence.

The ancient name for Sri Lanka was Taprobane Isola, a term that was used by the ancient Greeks and Romans when describing this mysterious and distant source of cloves and cinnamon. By the time Claudius Ptolemy was crafting his work in the second century CE, Roman merchants were sailing on her emporia directly, setting off from ports on the Egyptian Red Sea and using the monsoon winds to cross the Indian Ocean.

The rich island loomed large in the minds of many great geographical thinkers – including Ptolemy himself. As a consequence, Taprobane is often depicted as an enormous island on early maps. Throughout the Middle Ages, the wealth of the Indian Subcontinent continued to flow into Europe, albeit through the Islamic world. Looking at Ptolemaic maps of the Indian Subcontinent, Taprobane’s disproportionate size to its surroundings is striking – in particular compared to India itself, which in some cases hardly figures on the first European maps of this region. This conceptual error was gradually remedied in the 16th century, as Portuguese navigators and conquistadors began mapping their new mercantile domains in the Indian Ocean.

While our map does not depict the Indian Subcontinent and therefore omits the comparative context, one does get a sense that the dimensions of the island have been exaggerated in this map as well. Even so, the island correctly retains its tear shape (although in a somewhat angular form), just as many of its features constitute actual physiographic traits of the island. In addition to the many settlements and port towns along the island’s coasts, the map is dominated by two large mountain ranges at the center. These ranges are obviously of some importance, as both have been depicted with pictorial detail and have been labeled. Galib Monti in the north most likely corresponds to the central highlands, whereas the Males Monte in the southern part of the island constitutes the large central massif known as the Knuckles Mountain Range.

When appreciating the details of this map, it is vital to remember how passionate Berlinghieri was about Greco-Roman culture and learning and that Ptolemy would have been writing his Geographia at a time when Roman trade with Sri Lanka was at its highest. In Egyptian ports like Berenike or Myos Hormos, merchants and sailors from all around the Indian Ocean littoral abounded, and scholars like Ptolemy found in these people a crucial source to understanding the world beyond the horizon.

There can be little doubt that Ptolemy would have drawn heavily on this kind of experiential knowledge as he compiled his massive list of toponyms and terrestrial descriptions for the Geographia. Likewise, more than a thousand years later, Berlinghieri and Tedesco’s ability to compile a map of Sri Lanka that was so rich in detail at this early stage of European cartography was linked to the cosmopolitanism along the Indian Ocean at the time.

Context is Everything

The current map comes from Francesco di Niccolo Berlinghieri’s ‘Septe Giornate della Geographia’ (Seven Days of Geography), which was completed around 1479 and printed in Florence in 1482. It is generally regarded as the third printed atlas of the world (following the Bologna edition of 1477 and the Rome edition of 1478) and the first atlas ever to be printed in vernacular Italian. But where the previous editions were attempts to enhance the original translation with maps and a more up-to-date vernacular, ‘Septe Giornate’ was something quite different.

Berlinghieri had many passions, but two of his greatest were Classical Greek learning and poetry. In this unique work, Berlinghieri combines the two to approach the subject of geography in a completely new way. It is, in essence, a paraphrase of Ptolemy’s original text in Italian verse. In his seminal book on early printed maps (1987), Tony Campbell describes it as follows: “The Geographia of Francesco di Niccolò Berlinghieri (1440-1501) is not an edition of Ptolemy; it is rather a description of the world in Italian verse derived from classical and contemporary sources” (Campbell 1987: 124).

The ‘Septe Giornate’ included 31 engraved maps, of which the first was a World map, and the remaining maps consisted of the regional tavola maps that were also known from the Bologna and Rome editions. Atlases of this early period naturally focused on the three known continents: Europe, Africa, and Asia. For the latter, Berlinghieri’s atlas included maps of Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Greater Palestine, Syria and Iraq, Persia, Arabia, the Caspian littoral, China, Tibet, Afghanistan, Baluchistan, India, and our map of Sri Lanka.

Like all the maps for the Septe Giornate, this map was compiled and engraved by the German printer and engraver Niccolò Tedesco. His skill in engraving copper plates allowed for much greater detail to penetrate the map, bringing the world to life in a new dramatic way. Even though Tedesco used the Bologna and Rome editions as inspiration for his maps, he added many details of his own volition and even created four entirely new or ‘modern’ compositions (i.e. Hispania Novella, Gallia Novella, Novella Italia and Palestina Moderna). The discovery of the Americas would soon mean that the introduction of these ‘modern maps’ became a more common phenomenon in the 16th century, but Berlinghieri and Tedesco appear to have been the first to come up with the idea.

Most scholars agree that much, if not all, of the Septe giornate was likely completed by 1479. This included the maps, which were printed as a single large batch and subsequently bound. A significant number of extra map sheets were nevertheless left over from the original printing. After Berlinghieri’s death in 1501, these were purchased and bound into a new edition with a new title page that was issued around 1503-1504. The majority of intact copies that reach the open market today are this edition. Individual sheets are exceedingly rare. Because no revised status of the maps was ever printed, it is impossible to ascertain with certainty to which category our map belongs. But ultimately, every single copy of this map would have been printed in the same batch.

Before ending, a quick note should be made on the work’s dedicatory history. Berlinghieri’s work was originally to be dedicated to the Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed the Conqueror, who in 1453 had accomplished the unimaginable feat of taking Constantinople, finally ending the last vestiges of the Roman Empire in the process. But the sultan died in 1481, just as Berlinghieri was getting ready to publish. So instead, he dedicated his atlas to Federico da Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino. In what must have been a frustrating turn of events, the duke also died before the final edition was printed, but the dedication was maintained. At least two manuscript versions of the book were also created, dedicated, and gifted to Lorenzo de Medici and Federigo da Montefeltro (the son and new Duke of Urbino). The copy gifted to Lorenzo di Medici remains intact and in Florence (Helas 2002). Finally, a copy of the printed edition with a personalized dedication was sent to the new Ottoman Sultan, Beyazid II, and remains part of the Topkapi Palace library.

Cartographer(s):

Francesco di Niccolo Berlinghieri (1440–1501) was a 15th-century Italian scholar, humanist, and a keen student of Classical Greek learning. He was one of the first Italians to print a text based on Ptolemy’s Geographia, which he supplemented with his other great passion: poetry.

Niccolò TedescoNiccolò Tedesco (a.k.a. Nicolaus Laurentii; Niccolò di Lorenzo) was a German printer who lived in Florence during the late 15th century. He most likely learned the basics of printing in his native Wroclaw. Tedesco was among the first Italian printers to use copper plate engravings, and he was behind a number of important works from the Italian Renaissance.

Having moved from what is today Poland to Florence, Tedesco first worked in a nunnery of the Dominican Order, where the sisters served as compositors and printers. Among Tedesco’s most famous works, we find Cristoforo Landino’s commentary to Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (first printed in 1472) and the Septe Giornate della Geographia di Francesco Berlinghieri, which was among the first printed atlases based on Ptolemy.

Condition Description

Minor expert repairs to chipping and sewing holes.

References

Campbell, Tony (1987). The Earliest Printed Maps (1472-1500), British Library: London. Helas, Philine. (2002). The "Flying Map". Le 'Septe Giornate della Geographia', by Franesco Berlinghieri \ dedicated to Federico da Montefeltro and Lorenzo de Medici, and depictions of the world in 15th-century Florence (Cartography). Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 46: 271-320 Skelton, R.A. (1966). A bibliographical note prefixed to the facsimile of Berlinghieri’s Geographia, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum: Amsterdam.