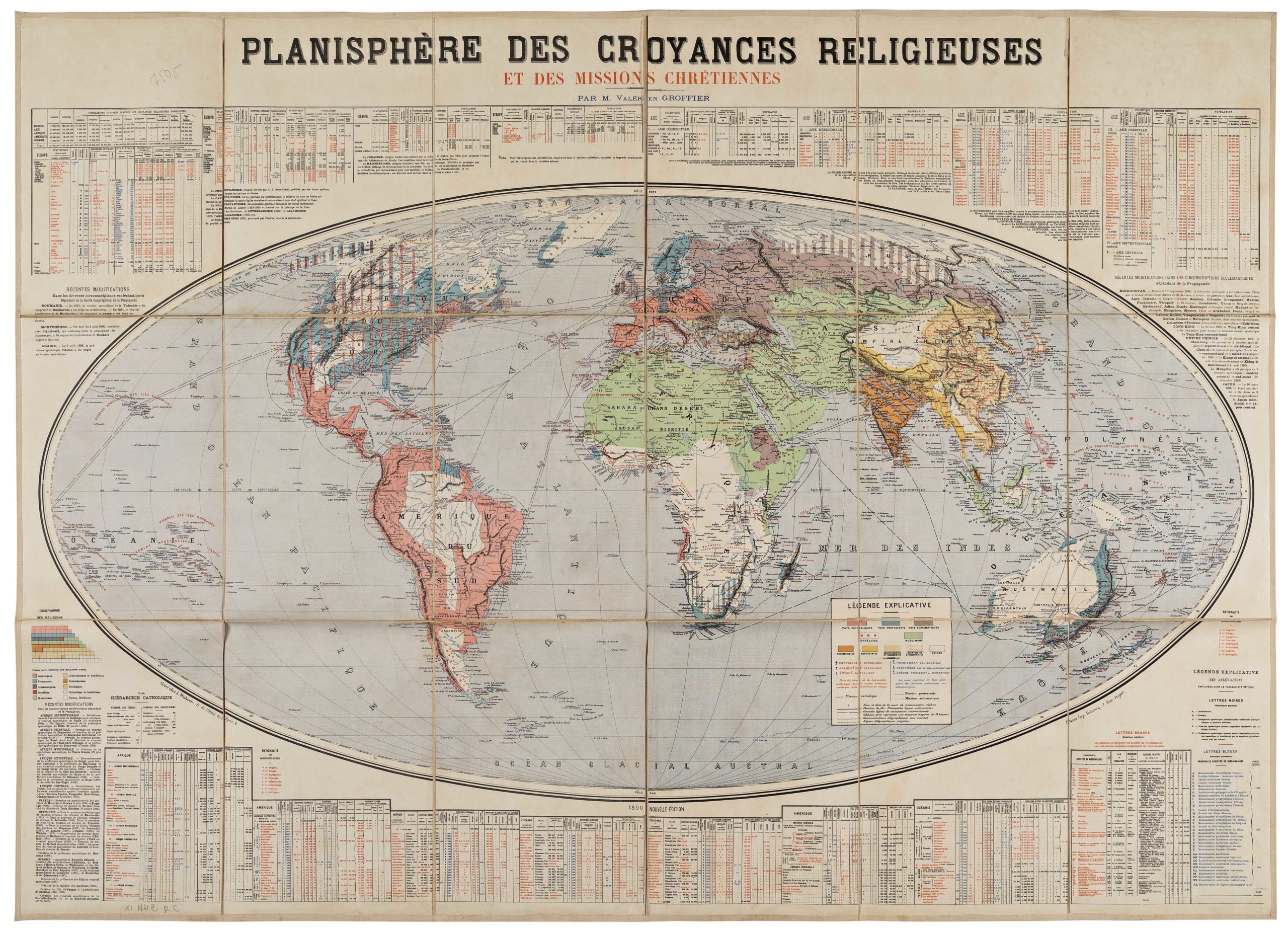

Sebastian Münster’s fascinating map of a new world.

La Figure du Monde Universel.

Out of stock

Description

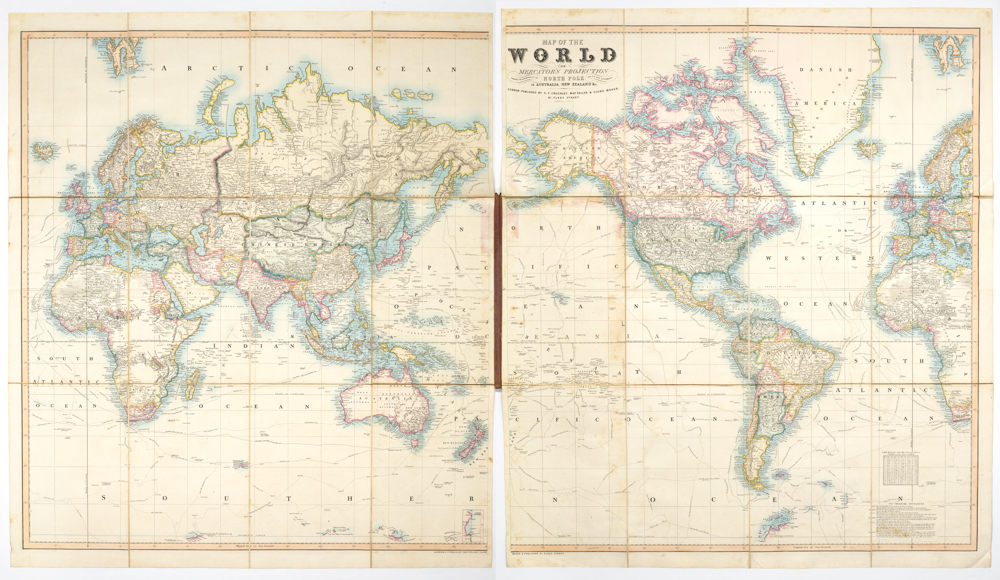

Münster’s map of the world was a seminal Late Renaissance creation that set aside old perspectives and invited its viewers to look upon the world anew.

Sebastian Münster’s most famous work, the Cosmographia, was first published in 1544. Within the pages of this seminal tome was a woodblock print of a world map, an example of which Neatline is excited to offer here.

The Cosmographia was among the most comprehensive and widely read geographical and historical works of the 16th century. It was a significant milestone in the history of cartography and remained popular for decades after its initial publication. Münster’s work played a crucial role in disseminating geographical knowledge during the Renaissance period, leaving a lasting impact on the development of cartography and geographical understanding. Due to its enormous popularity, the Cosmographia was also regularly updated and reprinted – including in new German, French, and Italian translations, making it a valuable resource for scholars, explorers, and geographers alike.

The world map featured in the Cosmographia was essentially based on a Ptolemaic view of the world, but it also incorporated the recent and mind-blowing discovery of the New World. Thus, the map depicts the known continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa and provides an early and schematic representation of the Americas.

One of the reasons this map is so exciting to the modern viewer is that despite his updates, Münster would hold on to some of the Ptolemaic dogma, leading to fascinating inaccuracies and mythical elements. One example, which is common in maps based on Ptolemy, is the disproportionate enlargement of Taprobana (modern-day Sri Lanka). This idea can be traced back to Classical Antiquity, when Roman traders sailed directly to Sri Lanka from ports on Egypt’s Red Sea coast. Another oddity that characterized Münster’s age of mapmaking was the inclusion of a ferocious bestiary, an element for which Münster was particularly renowned. In this map, as in most of his output, monsters lurk in the vast oceans leading European mariners to explore and map ever greater parts of the world.

Today, this woodblock print serves as a captivating glimpse into the world as it was known almost five centuries ago. It invites us to explore the frightening and exhilarating world of the Late Renaissance and reveals how perceptions of our planet have evolved through history.

Census

Neatline’s example of this map was printed from the second block carved for Münster’s Cosmographia and consequently considered the second state of the map (Shirley 92). The original state was issued in the first edition of 1540 and subsequently in the 1541, 1542, and 1545 editions (all in Latin).

For the 1550 edition of the Cosmographia, a new block was carved by David Kandel, who signed the block in the lower left corner of the map (generally faint but clearly visible in Neatline’s example). Another noticeable change from the first state was the removal of the eastern and western wind heads from the map oval itself, instead placing them outside the oval like the rest of the wind heads. The second block was used for all of the Basel editions of the map published between 1550 and 1587. A third block was produced for the 1588 edition.

As revealed by the map’s title and the writing on the verso, Neatline’s example comes from a French edition of the Cosmographia. French editions in the second state were issued in 1560, 1564, and 1568 according to Shirley. In 1552, a Latin/French edition was published, and in 1556, a German/French edition came out. Still, since the map’s title is normally maintained in Latin or German in these bi-lingual editions, ours must derive from one of the abovementioned three French translations, which all were published in Basel. One French edition of the Cosmographia was published in Paris in 1575 (Shirley 135), but this contained a completely different world map with distinct features and text.

Cartographer(s):

Sebastian Münster (1488-1552) was a cosmographer and professor of Hebrew who taught at Tübingen, Heidelberg, and Basel. He settled in Basel in 1529 and died there, of the plague, in 1552. Münster was a networking specialist and stood at the center of a large network of scholars from whom he obtained geographic descriptions, maps, and directions.

As a young man, Münster joined the Franciscan order, in which he became a priest. He studied geography at Tübingen, graduating in 1518. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Basel for the first time, where he published a Hebrew grammar, one of the first books in Hebrew published in Germany. In 1521, Münster moved to Heidelberg, where he continued to publish Hebrew texts and the first German books in Aramaic. After converting to Protestantism in 1529, he took over the chair of Hebrew at Basel, where he published his main Hebrew work, a two-volume Old Testament with a Latin translation.

Münster published his first known map, a map of Germany, in 1525. Three years later, he released a treatise on sundials. But it would not be until 1540 that he published his first cartographic tour de force: the Geographia universalis vetus et nova, an updated edition of Ptolemy’s Geography. In addition to the Ptolemaic maps, Münster added 21 modern maps. Among Münster’s innovations was the inclusion of map for each continent, a concept that would influence Abraham Ortelius and other early atlas makers in the decades to come. The Geographia was reprinted in 1542, 1545, and 1552.

Münster’s masterpiece was nevertheless his Cosmographia universalis. First published in 1544, the book was reissued in at least 35 editions by 1628. It was the first German-language description of the world and contained 471 woodcuts and 26 maps over six volumes. The Cosmographia was widely used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and many of its maps were adopted and modified over time, making Münster an influential cornerstone of geographical thought for generations.

Condition Description

Minor blemishes on centerfold.

References