With a land bridge connecting Africa and Asia, a massive Sri Lanka, the Mountains of the Moon, and more!

La Seconde Table Generale Selon Ptol.

$1,500

1 in stock

Description

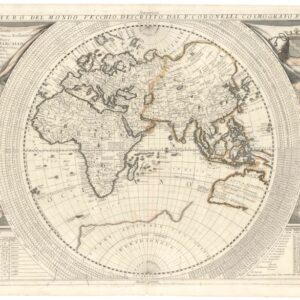

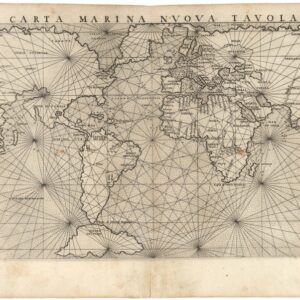

This excellent world map was created by Sebastian Münster, one of the most essential decisive mapmakers and thinkers of the mid-16th century. The map depicts the world as understood by the 2nd-century Roman geographer Ptolemy and was meant as a cartographic juxtaposition of the “old” or classical worldview against the revolutionary new insights achieved in Münster’s lifetime. It was first published in 1540 in an early edition of Münster’s Cosmographia and was since included in every edition of both the Cosmographia and the Geographia until Münster’s death. Neatline’s example of this evocative and essential map comes from a 1568 French edition of the Cosmographia.

The map is a fascinating glimpse into how the world’s geography was perceived from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Only with the Renaissance and momentous discoveries of the 15th and 16th centuries was this understanding finally revised. As such, it is, in essence, a retrospective map created at a time of great upheaval and change.

The source

Münster based this map on Claudius Ptolemy, a Roman geographer and astronomer whose geographical works were rediscovered in the 14th century. The map details the Oikumene, or the known and inhabited world, as it was understood at the height of the Roman Empire. In scope, this means coverage from the Atlantic frontier to Southeast Asia, or at least an early concept of it, and from the Arctic north to the Tropic of Capricorn in the south.

The map uses a conic projection, which was relatively common then. It is faithful to the original tripartite of the world into three great continents. In the upper left corner, we find a quite recognizable Europe. Below this, Münster depicts an enormous African landmass. While most of it remained palpably unknown at this stage, we do note the presence of at least two great rivers in Africa – the Nile and the Niger – as well as the depiction of the mythical Montes Lunae, or Mountains of the Moon, from which the ancients believed the might the Nile sprang. These mountains are depicted at the bottom of the map but are, in this case, unlabelled. Despite being largely unknown, Münster incorporates the knowledge conveyed in Ptolemy onto this map. Thus, we find long-forgotten place names like Meroë. Other labels, such as Arabia Felix, reflect the active trading that was going on in these regions in Roman times.

Asia is by far the largest of the three continents, and despite being largely unknown to Europeans at the time, it is also filled with fragments of information from the ancients. Thus, we see an enormous Sri Lanka (Taprobane) and a virtually non-existent Indian Subcontinent. This disproportional depiction is again due to Rome’s close mercantile contact with this island. Other geographical features typical of the Ptolemaic worldview include the rectangular Persian Gulf or the conflation of India and the Malay Peninsula. The most important feature is, nevertheless, the fact that the Indian Ocean has been depicted as a closed sea, bounded to the south by a massive unknown continent and unreachable by any other means than through Africa or the Orient.

While Münster deliberately tried to convey ancient geography in this map, he included many features that were unknown to Ptolemy. The most evident example is the enormous Scandinavian landmass extending into the unknown polar region. During the 15th century, Scandinavia was one of the European regions that enjoyed greater cartographic interest following the pioneering mapping efforts of Claudius Clavus and Olaus Magnus.

Why the retrospective?

Münster’s decision to include this ancient map in his otherwise modern Cosmographia speaks to Ptolemy’s enduring legacy and the influence the rediscovery of his work had on the geographical understanding of Renaissance Europe. In essence, Ptolemy’s geography consisted of numerous coordinates and associated place names – many mythological or without contemporary meaning. There is no evidence that Ptolemy ever created a visualization or map himself. Instead, this idea developed due to rediscovering this authority in an age of expanding globally. In this sense, Ptolemy laid the foundations for mapmaking, but he never appears to have made any maps himself. The fact that his rediscovery occurred about the same time the printing press was developed changed geography for good.

Sebastian Münster was Late Renaissance polymath and a very forward-looking scholar. His ambition was to map the known world, and that was a concept that was constantly changing and expanding. This ambition is reflected in his Cosmographia, which featured updated maps of Asia and Africa and the first complete rendition of the American continents in a printed map. The presence of a Ptolemaic world map was not only about juxtaposing the old with the new but was also meant as a tribute to the father of modern geography. It gave readers an essential visual reference for understanding how rapidly geographical knowledge expanded in the 16th century.

Census

This map was first published in Münster’s 1540 edition of the Geographia and was subsequently included in all subsequent editions of both that work and Münster’s Cosmographia until 1578. From 1588, new and posthumous editions of the Cosmographia were published by Sebastian Henricus Petri. These were given a new complement of woodcut maps based on the more up-to-date geography of Abraham Ortelius.

All editions of the Geographia were printed in Latin, whereas the Cosmographia was printed in Latin, German, French, and Italian editions. The present example conforms typographically with the 1568 French edition of the Cosmographia.

Cartographer(s):

Sebastian Münster (1488-1552) was a cosmographer and professor of Hebrew who taught at Tübingen, Heidelberg, and Basel. He settled in Basel in 1529 and died there, of the plague, in 1552. Münster was a networking specialist and stood at the center of a large network of scholars from whom he obtained geographic descriptions, maps, and directions.

As a young man, Münster joined the Franciscan order, in which he became a priest. He studied geography at Tübingen, graduating in 1518. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Basel for the first time, where he published a Hebrew grammar, one of the first books in Hebrew published in Germany. In 1521, Münster moved to Heidelberg, where he continued to publish Hebrew texts and the first German books in Aramaic. After converting to Protestantism in 1529, he took over the chair of Hebrew at Basel, where he published his main Hebrew work, a two-volume Old Testament with a Latin translation.

Münster published his first known map, a map of Germany, in 1525. Three years later, he released a treatise on sundials. But it would not be until 1540 that he published his first cartographic tour de force: the Geographia universalis vetus et nova, an updated edition of Ptolemy’s Geography. In addition to the Ptolemaic maps, Münster added 21 modern maps. Among Münster’s innovations was the inclusion of map for each continent, a concept that would influence Abraham Ortelius and other early atlas makers in the decades to come. The Geographia was reprinted in 1542, 1545, and 1552.

Münster’s masterpiece was nevertheless his Cosmographia universalis. First published in 1544, the book was reissued in at least 35 editions by 1628. It was the first German-language description of the world and contained 471 woodcuts and 26 maps over six volumes. The Cosmographia was widely used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and many of its maps were adopted and modified over time, making Münster an influential cornerstone of geographical thought for generations.

Condition Description

Very good. Light marginal soiling and some scuffing to centerfold.

References