Gorgeous and richly-detailed Late Renaissance bird’s-eye-view of Florence, Italy.

Nova Pulcherrimæ Civitatis Florentiae Topographia Accuratiss Delineata

Out of stock

Description

Key points:

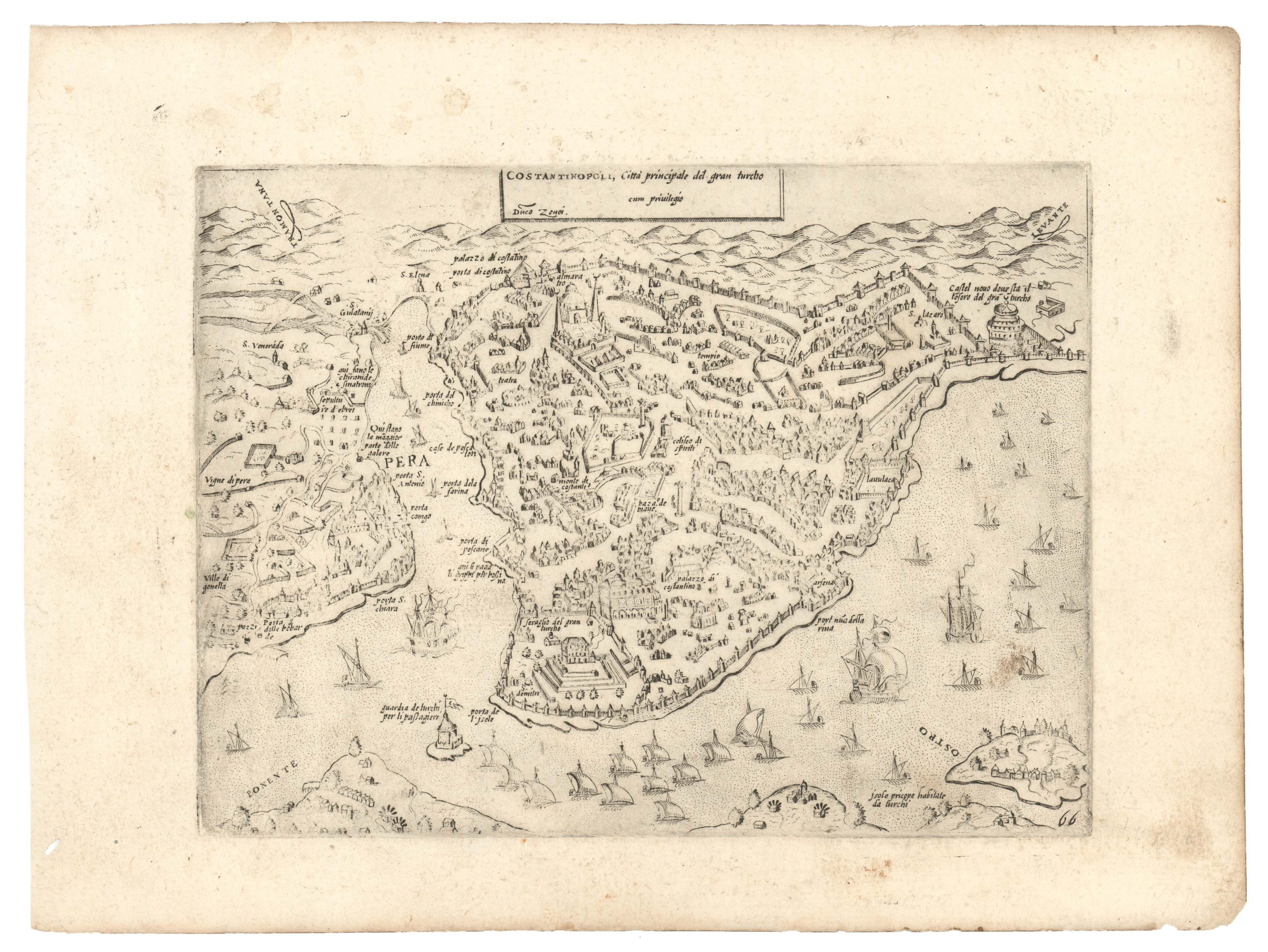

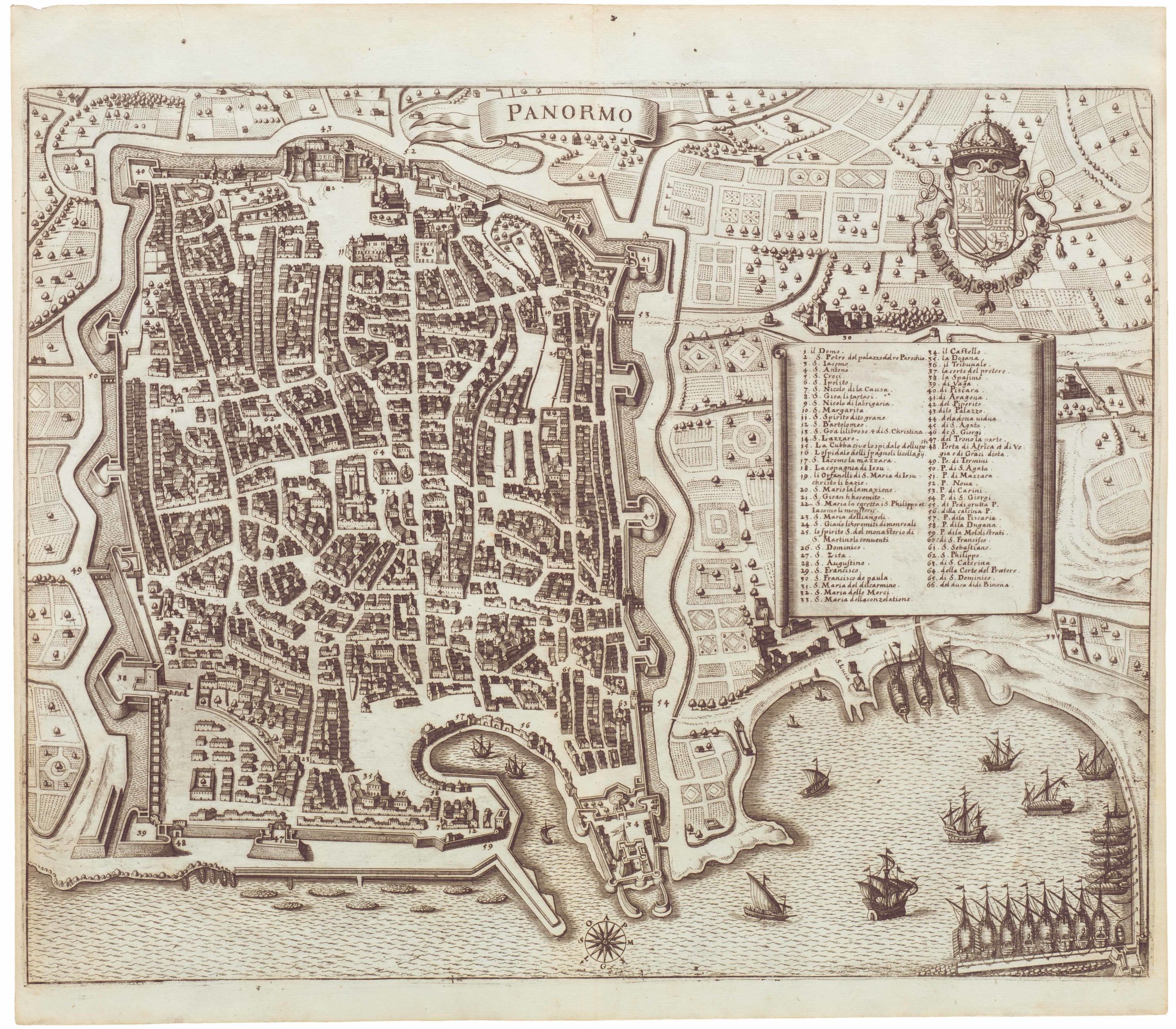

1. This skillfully executed Lafreri-school view of Florence documents the city in the Late Renaissance; the Uffizi has just been completed, the Ponte Vecchio is in the process of being converted to a locus of goldsmiths and jewelers.

2. It depicts many structures which were subsequently destroyed during World War II.

3. It is an optimal example of the great advances in axonometric urban mapping achieved in this period.

It is rare that one comes across something as exhilarating and lavish as the work presented here. Compiled with meticulous accuracy and the refined aesthetic sense of a Renaissance master, this copperplate engraving provides a magnificent bird’s-eye-view of 16th century Florence. It is not just an innovative and dynamic composition of the most important cultural hub of the Renaissance, but a time capsule that catches this great city in its final throng of historical greatness. With the immaculate details this chart offers, one can not only rediscover the Florence of the Medici, but a Florence that during the Renaissance was transformed from Medieval Episcopalian seat to a globally impacting nucleus of thought, science, art, and music. It is from this place, at this time, that many of the most cherished foundations of Western Civilization were laid down.

Visiting Florence in the 19th century, Mark Twain was overcome by its historic beauty and referred to it as “the fairest picture on our planet.” This map is an attempt to capture and depict this picture at its fairest. Despite being produced in the competitor city of Venice by a mapmaker from Brescia, the work is an enduring testament to the greatness of a city that fostered the likes of Dante, Michelangelo, Galilei, and Da Vinci. This notion of greatness, of worthiness, saturates the map both in its design and execution, and is one of the elements that make it so desirable to this day.

Bird’s-eye-views of the great Italian cities of the Renaissance were not unusual in the 16th century, although they were rarely executed with the kind of attention to detail seen in this map. The plans were popular for a number of reasons and many printers and cartographers were producing similar urban vistas at the time. The master of them all was the great Antonio Lafreri, a Burgundian cartographer and engraver active in the 16th century. Rome and Venice were Italy’s great centers of commercial printing and cartography at this stage. Settling in Rome around 1540, Lafreri was thus in the midst of it. Over the next three decades, he produced a plethora of maps and city plans for paying clients, cementing his name as one of the most important Italian publishers and printers of the era. The types of commissions entrusted to Italian cartographers at this stage were highly variegated and resulted in a broad array of different sizes, types, and styles of maps. Around the middle of the 16th century, some of the larger publishers began compiling their maps into bound volumes, though these do not seem to have had much structure or thematic focus at first. In 1570, Lafreri followed this trend and created a similar collation of maps and plans, but the systematic quality of his work made it stand out from its contemporaries. To this day, we still use the term ‘Lafreri Atlas’ to denote this category of early map collations originating in Late Renaissance Italy.

Our map may thus aptly be termed a ‘Lafreri-school view’ of Florence. It was executed by Donato Rascicotti, one of the leading cartographic printers operating in Venice between the end of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century (see biographer notes). It is an exhaustive and very rare town plan that renders in intricate detail all the monuments, bridges, houses, gardens, streets and fortifications of this great city. The vista, while imbued with many new features, was likely drawn from an earlier plan of the city done by Stefano Buonsignori (d.1589). Buonsignori was an Olivetan monk in the service of Francesco I, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. Among his many tasks, was the compilation of new maps for the Duke’s court. In the spirit of the Renaissance and the dawning age of exploration, Buonsignori’s maps drew on the latest information and applied the most cutting-edge techniques in their rendition.

Between 1576 and 1584, Buonsignori produced a now famous axonometric plan of Florence. Axonometry essentially means that the plan follows predefined axes or sight lines. But the true innovation was positioning the lines of sight perpendicularly to the plane of projection. This allowed an object to be rotated around one or more of its axes, and thus made it possible to show multiple sides of that object simultaneously. This bold technique would come to define an entirely new paradigm in mapmaking, epitomized in the many magnificent birds-eye views of the period. Our chart constitutes one of the first great successes in that regard. It is not, as some scholars have claimed, a reprint of Matteo Florimi’s 1595 engraving of Florence (pace Boffito & Mori). If anything, one might argue that it is the other way around.

The view presents us with the entire city as defined by its great circuit walls. Within the city, every street, piazza, and thoroughfare is visible, and many of them have been numbered and identified in a legend entitled ‘Notable places’ (Luoghi Notabili) in the lower right corner of the map. Flowing through the heart of the city is of course the great Arno River, which originates in Florence’s mountainous hinterland and empties into the Ligurian Sea at Livorno. Taming its violent flow we find Florence’s famous bridges, the oldest and most famous of which is the Ponte Vecchio, characterized by its triple arches and the row of narrow structures on the bridge itself. Built in 1345 after a flood had torn down an even older bridge at this location, the Ponte Vecchio was the only Renaissance bridge in Florence to survive World War II (probably because it was too narrow to accommodate artillery crossings). Among the architectural casualties of World War II was the Ponte alla Grazie (entitled ‘Ponte Rubaconitti’ in the map’s legend), just upstream from Ponte Vecchio. This bridge, which is the one depicted in our chart, had stood since the late 13th century, but was destroyed by German forces during their withdrawal from Italy in 1944. Being compiled in the late 16th century, our chart shows a total of four intra muros bridges across the Arno. Down stream from the two bridges already mentioned, we find the Ponte Santa Trinità and the Ponte alla Carraia.

The Ponte Vecchio is an apt place to start a tour of Florence, both for the modern visitor and in regard to this map. This is the heart of Renaissance Florence. It leads visitors and inhabitants alike from the newer south side of the city to the older northern center, where we find famous architectural masterpieces such as the Duomo and Uffizi Galleries.

Built on the three massive arches which still carry it today, the bridge was originally equipped with a line of butcher shops. Their location on the bridge was initially strategic, as this location allowed them to dump their waste directly into the river below. Gradually, however, this practice created such an serious odor and hygiene problem that it had to be dealt with. The man to do it was Ferdinand I de Medici. He had ascended the throne of the Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1587, after Francesco I (Buonsignori’s patron) had been murdered. Among his earliest initiatives was the permanent removal of the butchers from the bridge, replacing them with the goldsmiths and jewelers who still occupy it today. Our map is smack in the middle of that transition, and from the rather simple units on the bridge, we may well presume that this is one of those rare images that was produced before the famous conversion of Ponte Vecchio to a symbol of the city’s mercantilism and wealth. It is also one of many examples of why this map constitutes a window into a particularly important time for the city.

Stepping into the northern part of the city from Ponte Vecchio, one ascends via the ancient Via Calimala before culminating on the quadratic Piazza della Signoria, which in turn fronts one of Florence’s oldest and most famous buildings, the 13th century Palazzo Vecchio. Moving north from here, one soon ends on the beautiful double-square that constitutes both the geographic and architectural heart fo the city. Approaching the square from the river, we find the octagonal Battistero di San Giovanni (Baptistery of St John) on the left, and Brunelleschi’s magnificent dome of the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore (or il Duomo), completed a century prior, on the right. Both are architectural masterpieces, one of the Romanesque and the other of the early Gothic period. Like today, one notes that the piazza on which this truly monumental cathedral is built constitutes a tight space, with the surrounding cityscape hugging the contours created by the cathedral’s outline.

Downstream from the Ponte Vecchio we find the Ponte Santa Trinità, which leads across the river to Piazza de Lenzi and down past the splendid palaces of Palazzo della Strozzi and Palazzo Tornubuoni, which no longer exists. Even further down stream, the Ponte alla Carraia hits the Piazza de Rucasoli, from where one might proceed north to the large open square fronting the Gothic-Renaissance Church of Santa Maria Novella, which was the first of the great basilicas to be built in Florence.

On the east side of the Ponte alla Grazie instead, we come to another major north-south thoroughfare, today known as the Via dei Benci. Hanging right, one is soon lead into the Piazza Santa Croce that fronts the 15th century Basilica of the same name. The Basilica is not only famous for its Neo-Gothic architecture and the tombs of Michaelangelo, Machiavelli, and Galileo Galilei, but also because its chapel frescoes, many of which were painted by Giotto di Bondone – another of Florence’s famous artist sons.

In crossing the Ponte alle Grazie, visitors are provided with the only river-view of the magnificent Uffizi Galleries. Begun in 1540 by Giorgio Vasari as offices for the Florentine magistrates (hence the name), by the time the building had been completed in 1581, the upper floor had been converted into the private viewing galleries for the Medici family’s enormous art collection. While this spectacular space and its even more spectacular content would only be opened to the public after the collapse of the Medici dynasty in 1765, it remains one of the earliest concepts of a modern museum in the world. At the time when this chart was compiled, the Uffizi had only just been completed yet already stood as one of the most celebrated and impressive public buildings in the city.

While we can hardly provide descriptions of every single historical building in Florence here, it does not require much inspection of the chart to realize that one can recognize a vast array of historically verified or still standing buildings. Worth delving a little into are the aforementioned fortifications of the city, which not only served as a protective emblem of their urbanity, but which defined the urban perimeter for centuries. Located in the upper left of the map we find the Fortezza di San Giovanni Battista or Fortezza da Basso – the largest of Florence’s many historical buildings. Constructed in the 1530s, this star-shaped fortification was inserted into the much older walls in order to guard the city’s northwestern flank and garrison its soldiery.

The city walls themselves date back to the late 13th – early 14th century, but were built on much older foundations. Florence was established around 59 BCE as a Roman colony, and in line with other Roman settlements along the Via Cassia, it was provided with city walls in order to define it as such. Roman Florentia was constructed along the traditional model of a castrum or military encampment, with a major north-south thoroughfare (cardo maximus) and a major east-west one (decumanus) intersecting each other at the heart of the city. Despite continuous growth beyond the scope of the original colony, the Roman orthogonal lay-out dominated town-planning well into the Renaissance, as is evident from this chart. The thoroughfares would usually culminate on monumental and defendable gates, which on our map are readily visible – and in most cases numbered.

When the city began construction of its third generation city wall in the late 13th century, the gates were constructed first. This both ensured that the walls aligned more or less with the existing urban infrastructure, but also provided an anchoring point for the enormous project of erecting the curtain walls. Roman infrastructure, not only of the city, but of the surrounding roads, meant that orientation towards the cardinal points was maintained into the 16th century and beyond. Consequently, the main gates, Porta alla Croce (137), Porta San Gallo (135), and Porta al Prato (133) face east, north, and west respectively.

Context is everything

The Lafreri school was a school of cartography that was founded or inspired by the Venetian/Roman master printer Antonio Lafreri. We have already discussed his important contributions to cartography in the description above, but will investigate some of these issues and their importance in relation top this map a little further here. Lafreri’s atlases were published around 1570, the same year as Abraham Ortelius published his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, which traditionally is viewed as the first atlas, as it is the first book that systematically arranged maps of uniform sizes. Yet Ortelius neither depicted Atlas, nor used the term as part of his title. The term atlas was first applied towards to the end of the 16th century, when Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator published a volume comprised of more than one hundred maps that Mercator had re-drawn to a smaller and more uniform format, which was suitable for binding into a tome. Even though the term was intended as a neologism for a geographical treatise, Mercator became the first one to apply the term atlas to his volume. But even though he may have coined the name, the notion was not entirely new. On the frontispiece of his 1570 atlas, Lafreri had included an engraved image of the Greek Titan Atlas, who was condemned to carry the heavens on his shoulders, making him one of the first to draw a parallel between this new cartographic concept and the mythological figure that would come to name it.

In regard to the city itself at this time, Renaissance Florence was the product of a more of less continuous population growth spanning from Antiquity and lasting throughout the Middle Ages. Becoming an Episcopalian seat no doubt cemented its importance, but even without that, the city’s position on both north-south and east-west trade routes secured its importance and wealth as a mercantile hub. Rascicotti’s view, like those of his immediate predecessors, offer us a unique glimpse into the city during its heyday. Many of the advancements and achievements instigated by its sons and daughters had not only taken place when this map was drawn, but were beginning to take actual effect. We are in other words witnessing Florence as it became, and while more than four centuries old, one can only view this chart as a modern and forward looking document.

Cartographer(s):

Donatto Rascicotti (also written Rasciotti, Rasicotti, and Rosigotti) was a Venetian printer, publisher, and merchant born in Brescia in the middle of the 16th century. He was active between 1572 to 1598, primarily in Venice, but probably working out of Bologna and Rome as well.

Rascicotti can probably be identified with the Donato Resegata “stampatore di disegni,” arrested in Rome in 1577 and accused of stealing drawings from the studio of Antonio Lafreri. In 1598, he gained permission to publish by the Doge of Venice and had a shop at the Ponte dei Baretteri. Almagià describes Rascicotti as an editor of maps engraved by Giovanni Battista Mazza and Bertelli.

Condition Description

Wear along the edges; trimmed.

References

Mori-Boffito, p. 45/7; Bury, The Print in Italy, p. 232.