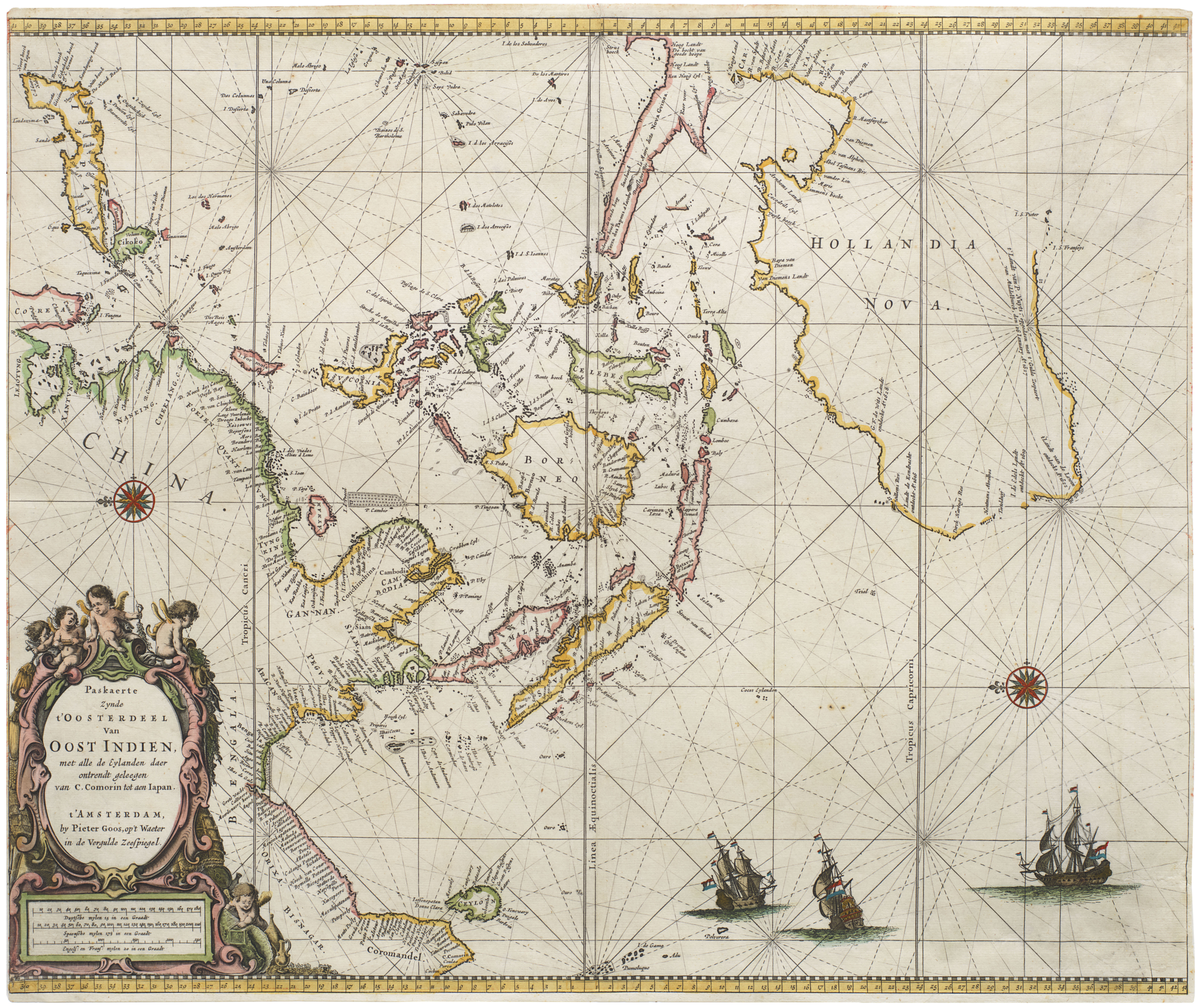

A cornerstone map for the historical cartography of Japan.

Iapponiae Nova & accurata descriptio.

$5,800

1 in stock

Description

A direct link to the now lost Ignacio Moreira manuscript map, the first scientifically accurate chart of Japan.

A reflection of the crucial Jesuit contribution to mapping Japan.

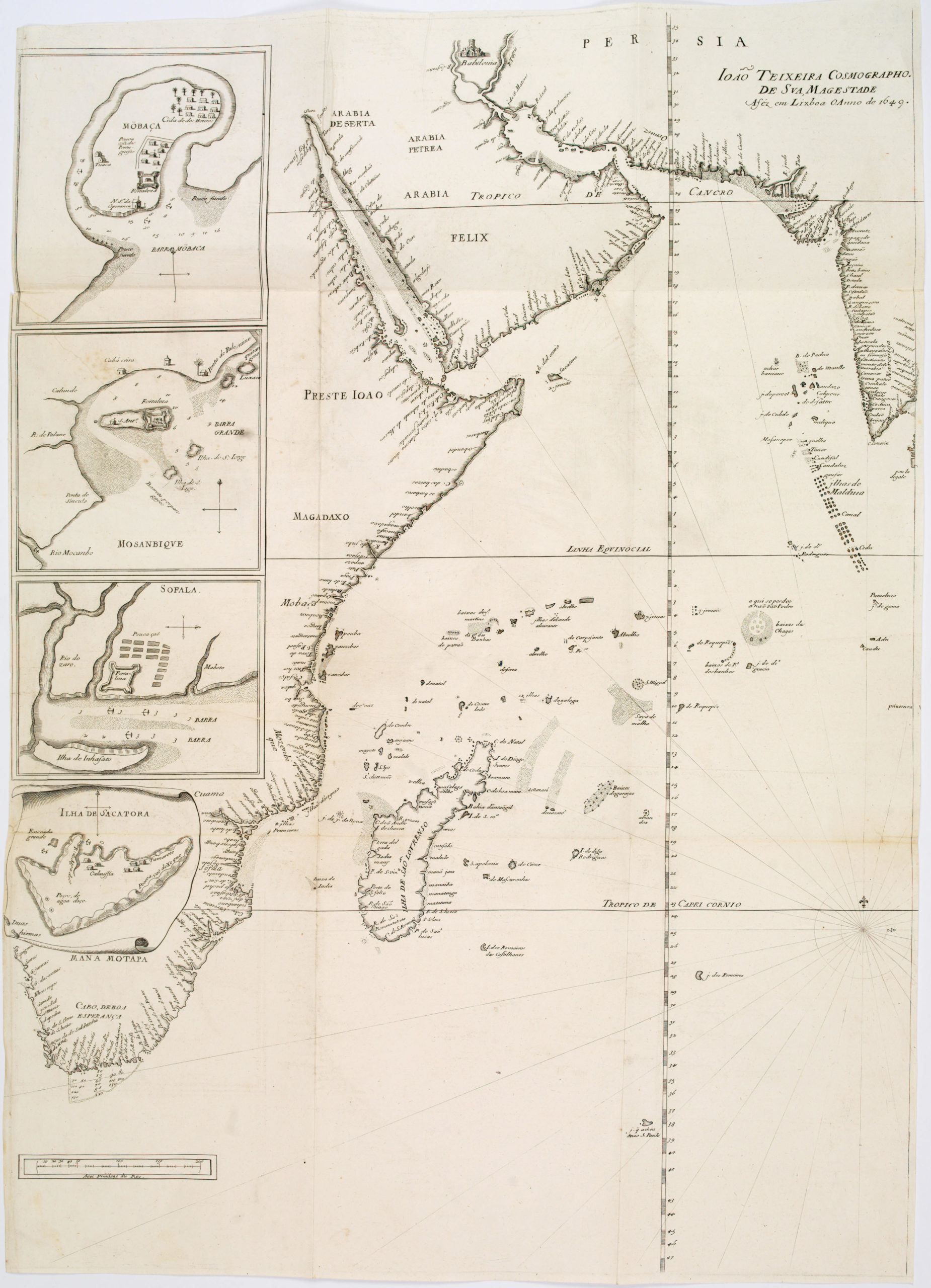

A scarce and important 1646 map of Japan, published in António Francisco Cardim’s book Fasciculus e Japponicis floribus, suo adhuc madentibus sanguine. It displays Japan as divided into 66 provinces, while the numbered list at the top-left and top-right notes the location of Jesuit missions (predating the suppression of Christianity described below). The use of crosses is not explained but presumably represents the presence of a Christian community. The inclusion of Yezo (Hokkaido) at the top-right is notable, as this region was still a frontier inhabited primarily by indigenous Ainu people. An illustration of a ship at the bottom commemorates the landing of St. Francis Xavier in Japan in 1549, the first Christian missionary to do so.

Japanese placenames are rendered in the Latinized form used by Iberian missionaries, such as Cangoxima for Kagoshima, Nangasaqui for Nagasaki, Ozaca for Osaka, and Yendo for Edo (later Tokyo). The text at the bottom explains the successes of the Jesuits and Catholicism in Japan, with many converts, schools, and seminaries, but also hints at the contemporary troubles of the faith, noting that “many will die for Christ.”

Cardim’s account was published at a difficult time for the Jesuit mission and Catholicism in Japan, explaining his emphasis on martyrdom. In the early 16th century, Japan was disunified into fiefdoms of competing daimyo locked into incessant warfare. The arrival of Portuguese traders and missionaries helped to tilt the balance in local power struggles; many daimyo and samurai in southern Japan, where the Portuguese were most active, converted to Christianity to gain favored access to Portuguese firearms.

Over the course of the 16th century, warlords used new weapons to consolidate power, though the most powerful unifiers had a complex relationship with Christianity. Oda Nobunaga was a patron of the Jesuits and paid for the construction of the first Catholic Church in Kyoto. His successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, attempted to ban Christianity as a way of reining in southern daimyo, but this ban was not strictly or uniformly enforced. The third great unifier, Tokugawa Ieyasu, was deeply suspicious of Christianity because he assumed the Portuguese and Spanish wanted to use religion to establish a colonial foothold in Japan. Some of the daimyo most opposed to his consolidation of power were Christians from the southern provinces.

Thus, beginning in 1614, the Tokugawa outlawed Christianity, required people in the southern provinces to register with a local Buddhist temple, and expelled foreign missionaries. Local Christian communities fiercely resisted these measures, leading to an increasingly severe confrontation with the government. Christians were then forced to trod on images of the Virgin Mary and Christ and were imprisoned, tortured, and often executed if they refused.

Under dangerous and difficult circumstances, Christians attempted to practice their faith secretly, often developing syncretic and unorthodox interpretations of Christianity in the process, while others fled to Macau or Manila. Persecution increased even more after the 1637-1638 Shimabara Rebellion, which was not started for religious reasons but came to involve many hidden Christians. For a time, Catholic missionaries attempted to come to Japan and were shielded by local Christians. Still, they were almost always captured and executed (though there were some cases of apostasy, such as Cristóvão Ferreira). This era of Japanese Christianity is the basis for Endō Shūsaku’s famous novel Silence.

Census

This map appeared in António Francisco Cardim’s book Fasciculus e Japponicis floribus, suo adhuc madentibus sanguine, published by Typis Heredum Corbelletti in Rome in 1646. It is based on an earlier 1641 map by Bernardino Gínnaro in his book Saverio Orientale ò vero Istorie De’ Cristiani Illustri dell’Oriente…

Cardim’s map is only independently cataloged among the holdings of three institutions and is scarce to the market, while the entire book Fasciculus e Japponicis floribus, which may or may not contain the map, is cataloged in institutions worldwide.

Cartographer(s):

António Francisco Cardim (1596 – April 30, 1659) was a Portuguese Jesuit who spent much of his life in India, Macau, and Southeast Asia. As a young man, he was inspired by Francis Xavier and his mission work in the Far East, to the point that he added Francisco to his birth name. He joined the Jesuits at age 15 and, after his training, sailed to Goa for further preparation for mission work. He then traveled to Canton (Guangzhou), Macau, Ayutthaya (Siam / Thailand), Tonkin (Vietnam), and Lan Xang (Laos). While in Tonkin, he worked with two Japanese missionaries who were later martyred in their homeland.

After a severe illness and recovery in Macau, Cardim was sent to Rome in 1638 to take a position overseeing the East Asian Jesuit missions. While back in Europe, he worked on several books about Japan and the persecution of Christians there, all published in 1645-1646.

Condition Description

Good. Loss in left margin, not affecting the image. Areas of discoloration and foxing. Small holes on top half and wear along edge repaired with archival tissue. Verso repairs to fold line.

References

![[Sri Lanka] Tabula Duodecima Dasia.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/NL-01721_thumbnail-300x300.jpg)