Cruchley’s 1855 map of the world in original boards and marbled backing — a distinctive addition to any world map collection.

Map of the World on Mercator’s Projection showing the Discoveries at the North Pole and the New Settlements in Australia and New Zealand &c. additions to 1855

$3,800

1 in stock

Description

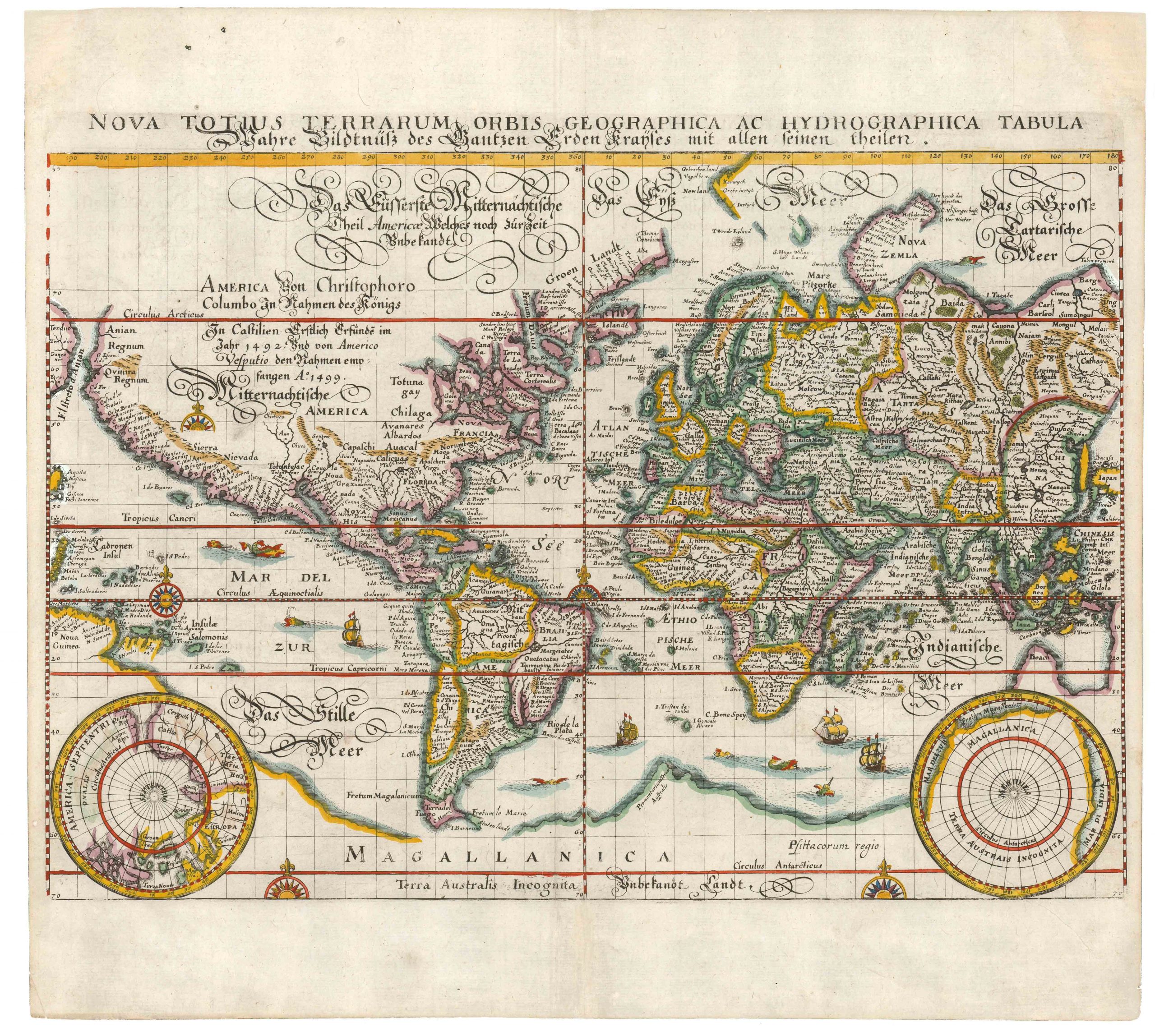

This fantastic world map is highly characteristic of the age in which it was produced; that is, a time when humanity – especially the colonial powers of Europe – thought themselves pretty savvy when it came to understanding the world’s geography. After all, European explorers, merchants, and warships had been plowing the high seas for centuries at this stage.

Nevertheless, the map is also a testament to a global political structure and hierarchy doomed to fail. In this light, the map is full of oddities and curiosities and errors, assumptions, and very short-lived constructions. Let us dive into a few of them here:

Russian America

One of the most interesting aspects of the map for an American audience is undoubtedly the labeling of Alaska as ‘Russian America.’ This was the common term for Russia’s colonial possessions in North America. While Russians had maintained a presence in America since the mid-18th century, it was not until Paul I issued the decree (or Ukasse) of 1799 that these settlements were formalized as Russian territory. While most Russian presence was in Alaska, with their capital at Novo-Arkhangelsk (modern Sitka), there were also small Russian colonies in California and three Russian forts in Hawaii (here still labeled the ‘Sandwich Islands’).

Initially, the Russian settlements in Alaska prospered, mainly due to the fur trade. However, excessive hunting, unreliable transport infrastructure, and domestic problems in Mother Russia led to a slow decline over the 19th century. By 1860, five years after this map was published, most Russian settlements in Alaska had been abandoned, and only seven years later, in 1867, the Russian territory was formally sold to the United States for just over seven million dollars.

India/Pakistan

In general, many labels are either strange or highly out of place in a modern context. The fact that direct British control of India had not yet been established is behind the naming of India as Hindoostan, just as Pakistan and Afghanistan have been dissolved into Baluchistan and Cabool (also labeled Afghanistan, but in a smaller font). South Asia had been a central pillar in the British Empire for some time at this stage, but direct British control in the form of the Raj was only established in 1858, three years after this map was issued. Other interesting labels include a distinction between China and the Chinese Empire, Thailand as Siam, Taiwan as Formosa, and the inclusion of a Tartar State in Bucharia.

Europe and Greenland

In Europe, the German Empire remains divided between Germany and Prussia, and we see a fledgling Austrian Empire bordering the still enormous Ottoman Empire. That said, the Greeks had, at this stage, managed to establish independence in the Peloponnese. The most notable European label is found in Greenland, which carries the words ‘Danish America’ in large bold lettering. Despite having a scattered indigenous population, Greenland was settled and colonized by Danes and Norwegians over centuries (starting as early as the late 9th century). Much of this was driven by commercial interests, with everything from whale blubber to a potential Northwest Passage playing a role. However, Greenland was only formally entered into the Danish Realm in 1814, the same year Norway became independent from Denmark. Their breach of Danish sovereignty and subsequent limited status on the world stage meant that the Norwegians could not claim Greenland (although they repeatedly tried).

When Cruchley published this map, Greenland had formally been part of the Kingdom of Denmark for some time; however, labeling it as ‘Danish America’ is new to us. Over the next half century, the term was applied, especially on maps of North America, including Greenland. In contrast, Cruchley’s map could, in some ways, be seen as a balancing counterpart to his inclusion of ‘Russian America.’

Missing areas of Africa and Arabia

A final note should be made on the many blank spaces that characterize this map. While large parts of the world have been explored, mapped, and colonized, enormous swathes of uncharted territory remain. This is seen most apparently in Central Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, which Westerners would only explore more thoroughly during the latter half of the 19th century and well into the 20th century. Yet great swathes of Central Asia, Australia, and the Indonesian Archipelago also remain blank spaces.

In the case of Africa, we see how European explorers began venturing deeper and deeper into the continent via its great rivers, discovering an abundance of physiography and culture along the way. This was the age of Mungo Park and David Livingstone, and it is apparent from the map how Africa’s rivers constituted the avenues for European discovery of the continent.

Cartographer(s):

George Frederick Cruchley (1797-1880) was an English map-maker, engraver and publisher based in London. He primarily made maps focussing on Britain and her possessions around the world, but he was particularly successful when it came to his maps and guides to London itself. Cruchley also produced at least two world maps, of which this is the later.

Condition Description

Engraved map on two sheets with bright contemporary hand-coloring, sectioned and laid on linen.

Slight staining, marbled endpapers with map seller's labels on each.

Contained in contemporary half morocco gilt boards with morocco gilt label to upper cover. Boards slightly stained, rubbed and worn at extremities.

References