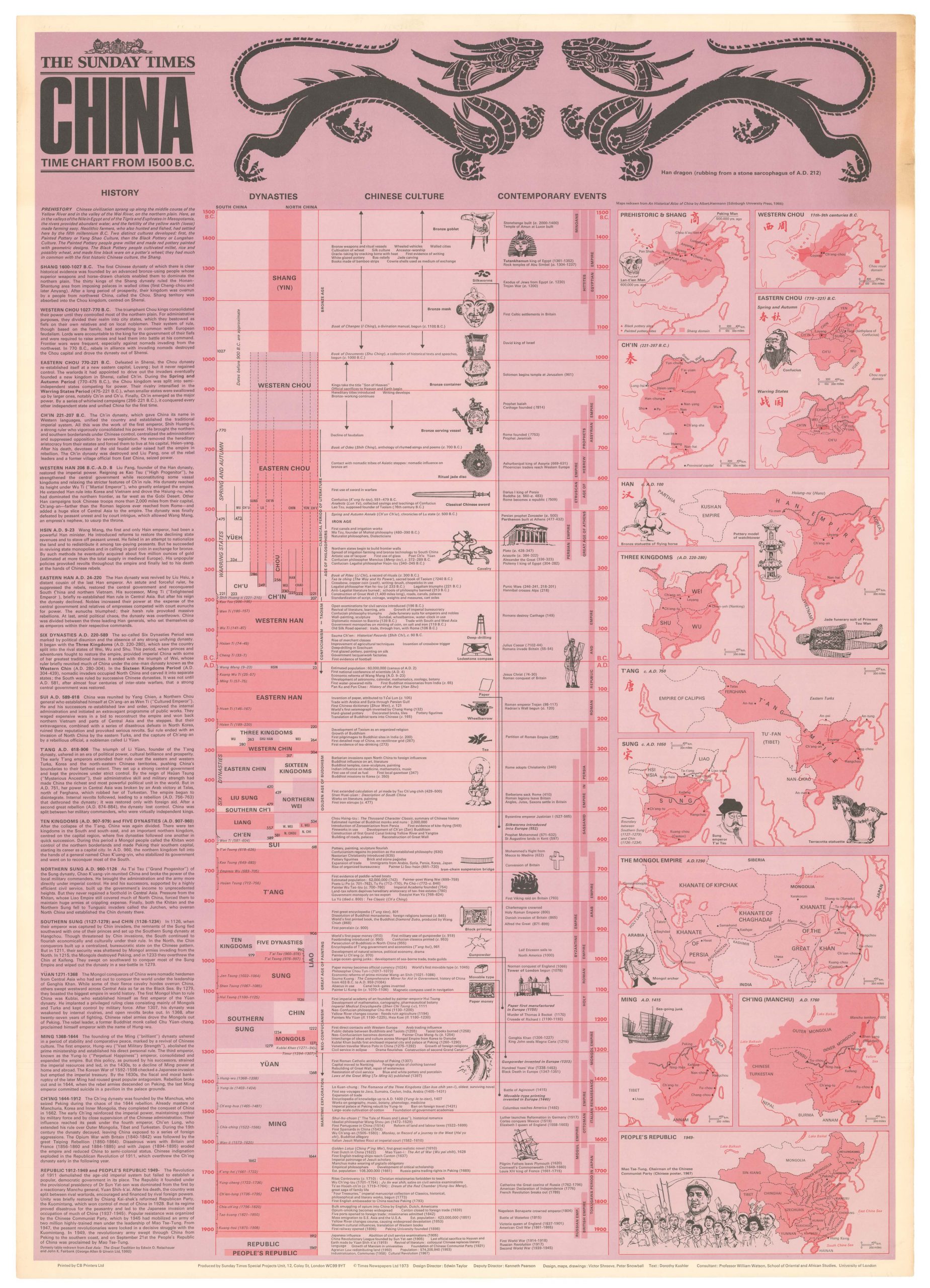

Nicolosi’s gorgeous four-sheet map of Asia — the first to use a globular projection.

Asia Ex Conatibus Geographicis Ioannis Baptistae Nicolosii S.T.D.

$4,800

1 in stock

Description

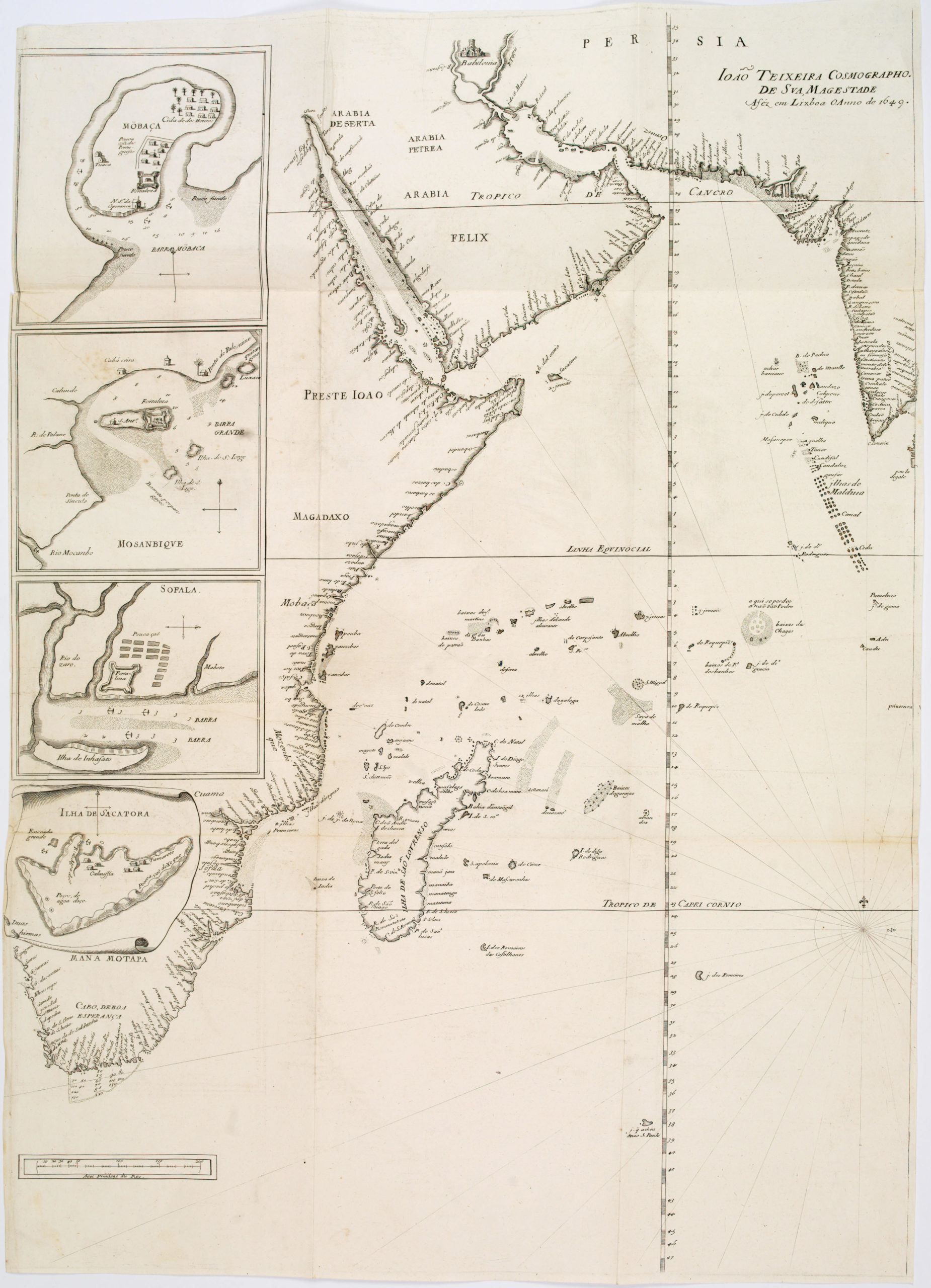

This spectacular four-sheet map of Asia — produced by Italian geographer Giovanni Battista Nicolosi on a commission from the Vatican — is a tour-de-force of 17th-century Italian cartography.

Published in Nicolosi’s seminal atlas, Dell’ Ercole e Studio Geografico, the map features compelling and curious depictions of such varied locations as Tibet, Formosa (Taiwan), Singapore, and the Philippines. It documents the extent to which European trade and missionary activity in the region had helped shed light on several long-standing cartographic mysteries there. In addition, Nicolosi’s Asia is one of the first post-Renaissance maps of Asia to be produced in the Italian schools of cartography and the first map of Asia to use the landmark Nicolosi Globular Projection.

In addition to the innovative projection used, this map is saturated with information from various sources. The scope of the map stretches from the Siberian Plains in the north to the immense archipelagos of Indonesia in the south and from Persia and Oman in the west to Japan, New Guinea, and the Philippines in the east. China figures relatively prominently and in great detail. This is especially so in the coastal regions, with which select European navigators would have some familiarity, but also inland; we find exciting information that suggests that the Vatican had a much more profound knowledge of the Asian landmass than one would expect. This is seen, for example, in the treatment of Tibet (split between Sheets 1 and 2), which, although located too far east, is neatly tucked between the ranges of the Himalayas and the provinces of Zhejiang (Sifan) and Sichuan.

By the mid-17th century, Portuguese traders had been sailing in China for over a century, and intelligence reports had long since reached Europe. Consequently, European intelligentsia understood the Great Wall of China regarding its function, monumentality, geographic scope, and historical significance. Nicolosi depicts it on his map with considerable prominence, showing the individual turrets colored in a soft red. North of the wall, it seems almost a cultural wasteland, with few toponyms or features noted on the map.

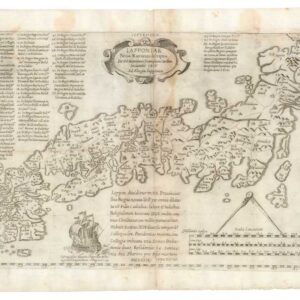

In general, several exciting features on this map highlight the early days of European colonial expansion that we are in. The world is still far from fully mapped, and even maps of relatively well-known regions such as Indonesia remain riddled with myths and misinterpretations. At the same time, the European expansion of geographic knowledge (and direct mercantile and military influence) was constantly expanding. By the time Nicolosi worked, even remote and isolated areas such as Japan and Korea were being mapped quickly and accurately. Korea is correctly shown as a peninsula, while Japan is a dense, elongated archipelago that is starting to be reminiscent of the real thing.

A fascinating detail is the island of Formosa at the bottom of Sheet 2. This is the island of Taiwan. Between 1624 and 1662 (and again 1664-68), the Dutch ruled the island, established it as Dutch Formosa, and instigated a brutal form of early colonial rule. The purpose was to build (and possibly monopolize) stable trade relations with Ming China and cultivate rice and sugar using imported Chinese labor. The Dutch presence on the island ended within a few years of this map’s publication, and so its conclusion constitutes one of those rare windows into a short but decisive period of history.

The keen Dutch and Portuguese interest in trading with the Spice Islands of Indonesia meant that Europeans began mapping these complex archipelagos in the early 16th century. However, most maps of the region at that stage were considered highly confidential and of stout national interest. This also meant that Greater Indonesia here is mapped in great detail and with impressive accuracy. Undoubtedly, Nicolosi had access to some of the treasured cartographic information on this region, for his rendition is unlike most of the other regions that he mapped in his continental charts. The Africa chart, in particular, is characterized by a very conservative approach that did not incorporate the latest reports and surveys. But in Southeast Asia, this is not the case. And even though islands like Borneo and Sumatra are slightly disproportionate in size compared to the surrounding regions, the outline, positioning, and content are remarkably accurate for a mid-17th century map.

There are, nevertheless, errors and myths that have been incorporated into this region. Irian Jaya, or Western Papua, has been depicted as a distinct island, separated from New Guinea. This distinction of Papua and Guinea as separate islands was not Nicolosi’s error but a recurring misunderstanding dated back to 1590. Most scholars believe it derived from an early mix-up of Irian Jaya (Papua) and the smaller island of Seram. Marco Polo’s Beach is shown below Java and Timor, foreshadowing the location of Australia. Hogeland and Batavia are demonstrated on a poorly known stretch of land that would become Carpentaria in northern Australia, with the strait between New Guinea and Australia still poorly charted.

Another small but fascinating detail is the inclusion of the coastal entrepôt of Singapore (Sincapura) in the lower right corner of Sheet 3. The traditional Western narrative about the emergence and development of Singapore as an international trade hub normally involves a process associated with Stamford Raffles and the British Empire. But Raffles arrived in Singapore in 1819, more than a century after this map was issued. There was a Chinese cantonment here at this stage, but despite its ideal location on trade routes, the Brits considered it inferior and desperately needed some British infrastructure to bloom. However, with Nicolosi’s map in hand, we can yet again confirm that the colonial development narrative, imposed in this case by the British, rarely corresponded to an objective reality and that in this part of the world, long-distance trade predates the arrival of the Europeans by centuries, if not millennia.

A final note should be made on including the fabled coastline and sound northeast of Japan, known (and labeled) as Terra di Jesso and Stretto di Jesso, respectively. Jesso is another tenacious cartographic myth that characterized the exploration and mapping of the North Pacific for more than a century. The etymology of this toponym is the Japanese Ezo-chi, a term used for the lands north of the island of Honshu. During the Edō period (1600-1886), it came to represent the ‘foreigners’ on the Kuril and Sakhalin islands north of Japan. As European traders came into contact with the Japanese in the 17th century, the term was adopted and incorporated rather uncritically onto European maps, where it – like on Nicolosi’s map – often is associated with the island of Hokkaido.

Jesso’s importance is traced back to Father Francis Xavier (1506-1552), an early Jesuit missionary to Japan and China. Xavier related stories that immense silver mines were to be found on a secluded Japanese island, and these stories were soon strengthened by Spanish traders spreading similar reports. The rumors became so tenacious and widespread that Abraham Ortelius included an island of silver above Japan on his 1589 Maris Pacifici map. Half a century later, the powerful Dutch East India Company sponsored two voyages of exploration to identify and possibly claim these rich lands for Holland. Abel Tasman led the first expedition in 1639 and the second by Maarten Gerritzoon Vries in 1643. Believing the Kuril island of Urup to be continental, Vries named it Compagnies Landt after his employer. Vries erroneously perceived Urup as the westernmost fringe of America, and mapmakers soon adopted this concept. Over time, variations occurred in this undefined land known as Jesso.

All of this was nonsense and would be swept aside in 1728 when Vitus Bering navigated and mapped the strait between Asia and America and many of the peninsulas and islands associated herewith. But while Bering may have dispelled the cartographic darkness of this region, one of the most important motivations behind the Kamchatka Expeditions was ensuring that potentially resource-rich lands were claimed for Russia and not some far-off European power. In that sense, even Bering was, to some degree, pursuing Father Xavier’s Jesso.

Nicolosi and the Dell’ Ercole e Studio Geografico

Giovanni Battista Nicolosi (1610-1670) was a Sicilian priest and cartographer working for the Vatican in Rome. Motivated by the ground-breaking maps of French cartographer Nicolas Sanson (especially those in his 1653 Index Geographicus), the Propaganda Fide of Rome commissioned Nicolosi to produce an atlas that could rival Sanson’s. Over the next seven years, Nicolosi labored intensively to meet his employer’s demand, and the outcome would be one of the most essential Italian atlases produced in the 17th century.

Nicolosi’s Dell’ Ercole e Studio Geografico was published in Rome in 1660 and again in 1671 as a posthumous Latin edition. The title referred to a comparison between the labors of Hercules and those he had sustained to complete a full description of the earth. In the Ercole, Nicolosi presented large four-sheet maps of all the continents as they were known in the 1650s (Africa, North America, South America, Europe, and Asia – twenty-two plates in all). The atlas also contained an essential double map of the world, which incorporated many of the continental map innovations on a global scale (e.g., both the dubious depiction of the Niger River, as well as the first relatively accurate inclusion of the Rio Grande). Consequently, both the 4-sheet maps of the continents and the two-sheet map of the world have become highly sought after by collectors and institutions alike.

The Ercole was dedicated to Giovanni Battista Borghese and consisted of two folio volumes printed by Vitale Mascardi. Composed of no less than 22 maps with associated explanatory text, the Latin edition of the Ercole (1670) allowed Nicolosi’s ideas to be fully integrated into the cartographic mindset of Europe. In time, the Ercole became one of the most critical geographical works of the 17th century. This was partly because of the incredible archives and sources available to Vatican scholars in the 17th century. Still, the main reason was that Nicolosi approached global mapping in a novel way. He combined the traditions and perspectives of 16th-century Roman and Venetian mapmakers with the latest approaches of contemporary greats such as Nicolas Sanson. This amalgamation of traditions and styles meant that Nicolosi could come up with an entirely new way of portraying the world – especially when it came to larger landmasses where the curvature of the Earth affected how such terrain could be portrayed correctly.

Nicolosi was the first to employ the so-called pseudo-perspective projection in which the established meridians were perfected by complimenting circular parallels. Over the following decades, and especially during the early 18th century, this projection technique – also known as the globular projection – became increasingly popular and was applied by seminal cartographers such as Guillaume de l’Isle and Aaron Arrowsmith. In the decades after Nicolosi’s death, the globular or Nicolosi projection replaced the stereographic projection popularized by Mercator, which had increasingly fallen into disuse. During the 19th century, the Nicolosi perspective became the standard cartographic projection technique, and it remains in use today.

Cartographer(s):

Giovanni Battista Nicolosi (1610-1670), also known as Giovan Battista, was a Sicilian priest, geographer, and cartographer who worked for the Vatican’s Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (or Propaganda Fide) under Pope Gregory XV. Officially, the Fide office was established to promote missionary work across the globe. Still, the reality was that it constituted an essential office for the maintenance and dilation of the Church’s power in an ever-expanding world.

Arriving in the papal capital around 1640, Nicolosi studied letters, sciences, geography, and languages. In 1642, he published his Theory of the Terrestrial Globe, a small treatise on mathematical geography, and a few years later, his guide to geographic study was issued, a short treatise on cosmography and cartography. Both works reflected a Ptolemaic worldview, but his guide to geographic analysis would soon serve as an introduction to Nicolosi’s real magnum opus, Dell’ Ercole e Studio Geografico, first published in 1660. On the other hand, his Theory of the Terrestrial Globe brought Nicolosi to the attention of broader scientific circles. It earned him the Chair of Geography at the University of Rome. In late 1645, he traveled to Germany at the invitation of Ferdinand Maximilian of Baden-Baden, where he remained for several years until he returned to Rome. Here, Nicolosi was appointed chaplain of the Borghesiana in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. This honor was conferred on him by Prince Giovanni Battista Borghese, whom Nicolosi had tutored and in whose palace he had lived since 1651. Years later, Nicolosi would thank the prince for his generosity by dedicating his most seminal work to him.

A considerable collection of Nicolosi’s unpublished work exists in the Vatican and other national archives. This includes a large chorographic (i.e. descriptive) map of all of Christendom, commissioned by Pope Alexander VII, and a full geographic description and map of the Kingdom of Naples, which was sent to Habsburg Emperor Leopold I in 1654.

Condition Description

Very good. 4-sheets, unjoined.

References

![[Sri Lanka] Tabula Duodecima Dasia.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/NL-01721_thumbnail-300x300.jpg)