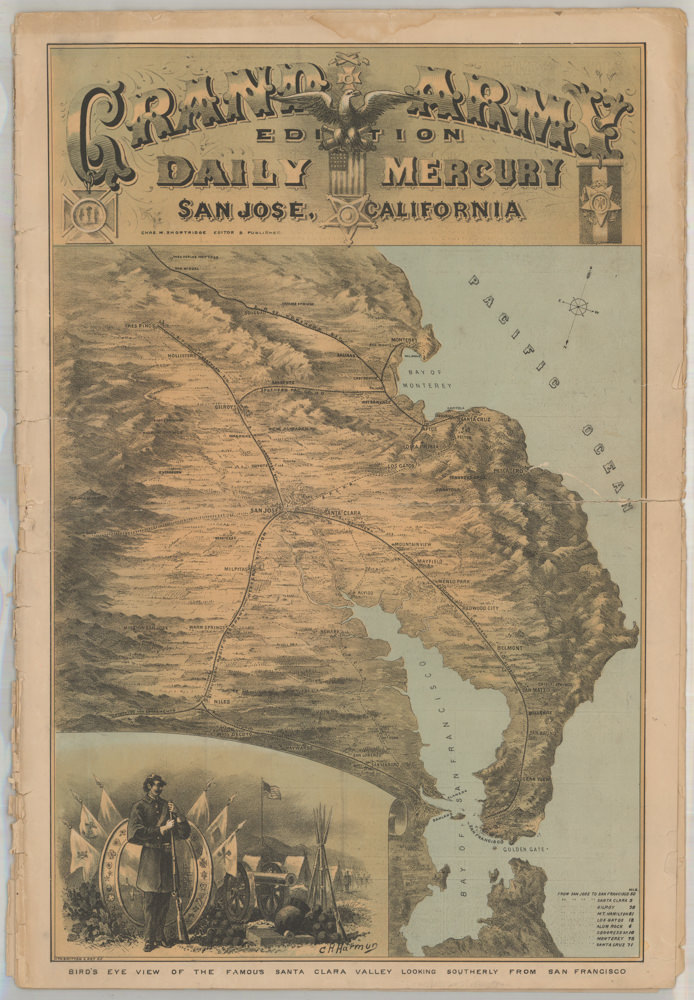

A monumental manuscript map of San Jose, the most comprehensive map of the city we have ever seen.

Map of the City of San Jose [manuscript].

Out of stock

Description

This is a very large (5 feet tall) 1917 manuscript plat or cadastral map of San Jose, a unique piece of San Jose’s history.

The map’s primary purpose is to denote property ownership throughout the city, marking the boundaries and size of lots, additions, tracts, and surveys, with owners noted for the larger pieces of property, especially along the outside of the city. The owners’ names reflect the ethnic mix of the area at the time, with Italian, Spanish/Mexican, German, Irish, and ‘Anglo’ names featured prominently (missing, however, are names from the city’s notable Asian-American minority, many of whom were barred from owning land by California’s 1913 Alien Land Law). Some of the names include recognizable Bay Area grandees, such as the ‘heirs of James Phelan.’ Perhaps the largest single landowner in the city was the Southern Pacific Railroad, a remnant of the generous land grants provided in the heady days of railroad construction in the 19th century.

Several San Jose landmarks can be easily spotted, such as the City Hall on Market Plaza (now Plaza de Caesar Chavez) was a large and impressive structure completed in 1889. The Convent of Notre Dame near center towards left was home to the first women’s college in California (now the Notre Dame de Namur University), chartered in 1851, and also is the basis for Notre Dame High School, tied for the oldest in the state, while the State Normal School on Washington Square (now San Jose State University) was the earliest established campus of what became California’s massive and renowned public university system. Luna Park, modeled on the eponymous amusement park in Coney Island in New York, and the adjacent ‘Base ball grounds’ near top are also worth noting.

Aside from property, roads, railways, streetcar lines, public institutions, waterways, and other features are also indicated to a great level of detail. This map dates from the height of the streetcar era; in the preceding years, several existing lines were consolidated under the San Jose Railroad Company, which itself had been acquired by Southern Pacific. Beyond the city center, electric railways provided interurban service throughout the Santa Clara Valley and San Francisco Peninsula. Some remnant cars from these lines now sit at San Jose’s History Park. The line running along the Alameda and Santa Clara St. was originally the San Jose and Santa Clara Railroad (or Railway), which was the first interurban railroad in California, when it opened in 1868, running horsecars between San Jose and San Francisco. Although most of this infrastructure was demolished in the decades following this map’s production, it served as inspiration and a basis for today’s VTA (Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority) system, while the West San Jose Depot at left-center here, which served the narrow-gauge South Pacific Coast Railroad, is the basis for today’s busy Diridon Station, employed by both Amtrak and Caltrain.

San Jose’s ‘Missing’ Minority

As much as the map reveals, it also omits or skirts certain elements of the city’s population and recent history. For instance, the site of the ornate City Hall on Market Plaza had been home to the city’s largest Chinatown, which burned down in 1887 at a time of intense anti-Chinese sentiment, when several discriminatory laws were passed against Chinese in the city. Although the fire’s origin is unknown, white residents had intentionally started fires in the neighborhood before, and several other Chinatowns in California were burned down around the same time. In any event, the fire department did nothing to help suppress the blaze, only to stop it from spreading to surrounding non-Chinese neighborhoods. Many of the residents of the neighborhood then moved on to other Chinese neighborhoods in San Jose (there were as many as five), especially Heinlenville, marked here as ‘China Town’ at the intersection of Taylor St. with North Sixth and Seventh Streets, and ‘Woolen Mills Chinatown’ – not marked here – near the intersection of Taylor St. and North First St. Anti-Chinese sentiment was so strong that at one point Heinlenville was surrounded by a high wooden fence topped with barbed wire to keep out arsonists and other malefactors.

Around the time this map was produced, increasing numbers of Japanese migrants were also arriving and settling in the same area, which came to be known as Japantown or Nihonmachi, though it maintained a significant Chinese-American community as well. This was the effect of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and similar state and city-level measures, which deprived California of the largest source of inexpensive immigrant laborers. After Japanese began arriving in large numbers in the late 19th century, similar sentiment against them and other ‘Asiatics’ (Koreans, Filipinos, Indians) grew, resulting in California’s 1913 Alien Land Law (passing both houses of the state assembly with near-unanimous support), which effectively banned Asian immigrants from owning property (this was followed in 1924 by a national-level exclusion on Japanese immigrants similar to the earlier Chinese Exclusion Act).

Despite these obstacles and general discrimination by the white community, immigrants tried and often succeeded in challenging or evading these laws. For instance, white landowners would often collaborate with leading members of the Asian-American community to provide them long-term leaseholds (far beyond the three-year leases allowed by the Alien Land Law), which were then subleased to members of the community, often in the same fashion, providing de facto ownership. Asian immigrants would attempt to place property in the names of their American-born children, until both the California and U.S. Supreme Courts judged such acts a violation of the Alien Land Law and not protected by the 14th Amendment. In 1920 and 1923, California passed revised Alien Land Laws meant to crack down on such activity and close loopholes, and these restrictions were not formally overturned until the 1952 California Supreme Court decision Sei Fujii v. California.

Census

The map was produced in 1917 by ‘Chief Engineer’s Office’ in San Francisco, though which firm this refers to is unclear (a similar designation appears on a contemporary map of the Western Pacific Railroad, OCLC 21817812). As San Jose had its own City Engineer’s Office at this time, the production of the map by an outside firm is curious, perhaps reflecting intended use for real estate investors in San Francisco. In any event, as a manuscript map, the present work is a unique production. We are aware of a handful of other cadastral maps of San Jose from the early 20th century in various institutional collections, but few approach the size and detail of the present map.

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Ink manuscript on linen. Some wrinkling and edge wear.

References