Early Manuscript Representation of the Iconic Madaba Map of the Holy Land.

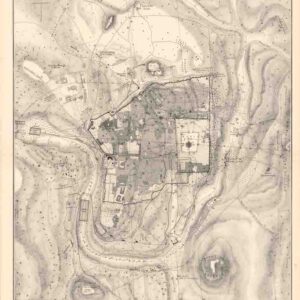

[Map of Medaba]

Out of stock

Description

This rare and visually striking manuscript, in pencil, ink, and colored pigments (including a gold border) on heavy-wove paper, depicts the celebrated Madaba Map, one of antiquity’s most extraordinary cartographic artifacts. This sixth-century mosaic is the oldest known depiction of the Holy Land, offering a remarkable view of the region.

Created in the late seventh century, the Madaba Map was a monumental mosaic spanning approximately 24 by 6 meters and comprising well over a million tesserae. In 1884, it was rediscovered beneath the ruins of an ancient Byzantine church in Madaba, Jordan, where large sections—some measuring up to 10.5 by 5 meters—were uncovered. Though the mosaic had suffered damage over time, the surviving pieces were salvaged, minimally restored, and incorporated into the floor of a new church on the same site.

The discovery gained attention when 1896 the mosaic was examined by Father Koikylides, librarian of the Greek Orthodox patriarchate, who produced an initial sketch and published his findings the following year. At the time, reaching Madaba was difficult, but dedicated scholars and explorers soon made the journey, documenting the mosaic and sharing their interpretations. One such drawing surfaced at an auction in San Francisco in the 1980s and is now part of the Israel Museum collection. Around 1901, architect Paul Palmer of Jerusalem created drawings based on a large-scale painted reproduction, which were later published in Leipzig in 1906 under the title Die Mosaikkarte von Madeba.

As interest in the map grew, its condition deteriorated due to fire, humidity, and continued use of the church, leading to further loss of imagery. In the 1960s, a German-led restoration effort sought to preserve what remained, though early copies provide crucial clues to its original form. Variations among these early renderings highlight the challenges in reconstructing the map’s precise appearance when it was first uncovered.

An Early Manuscript Rendition

The manuscript offered here is one of those early reproductions. A rectangular panel at the top right bears the date “1906,” suggesting it was created by an early visitor to Madaba. The image was hand-drawn in pencil and enhanced with colored pigments, including a gold border, resulting in a brighter and more vibrant representation than the fragmented mosaic that survives today.

With the East oriented at the top, the map spans from “Neapolis” (modern Nablus) on the left to Egypt and the lower Nile River on the right. The landscape is filled with geographical features, towns, villages, and Greek inscriptions, with additional embellishments where space allows, such as tiny trees, animals, and Biblical references. The mountains and hills are rendered in shades of gray, brown, and blue, while rivers are highlighted in blue, purple, and gold. The Dead Sea is particularly striking, featuring two large oared ships. Several Greek text panels describe the map’s historical significance, though it is unclear whether these originated from the original mosaic or were added by the copyist.

The map’s centerpiece is the oval-shaped depiction of Byzantine Jerusalem in the lower center. Though details are more difficult to discern in this smaller-scale copy, significant landmarks, including the Damascus Gate in the north, which led to a colonnaded central street extending toward a basilica at the far end, are evident. This representation played a key role in inspiring archaeological excavations following Israel’s capture of Jerusalem in 1967, leading to the rediscovery of the Cardo (the colonnaded street) and the Nea Church.

This version lacks some details of Palmer’s 1901 copy. However, despite dating to 1906, it seems to have been based on an earlier representation—possibly one predating Palmer’s work—as it includes details missing from his version. These missing elements likely reflect additional damage suffered by the mosaic between Koikylides’ first documentation and Palmer’s later visit. Further complicating matters, the Greek text panels in the margins differ significantly from those on the Israel Museum copy, suggesting a distinct lineage.

Census

A scholar researching the Madaba Map has identified eleven manuscripts held in European and Middle Eastern institutions, excluding the 1896 Israel Museum copy and the manuscript offered here. A thorough comparison of these copies could provide further insight into the map’s original appearance.

Conclusion

This early manuscript rendering is a rare, historically significant, and visually stunning document closely linked to the intense scholarly interest that followed the rediscovery of the Madaba Map. It serves as both a testament to early cartographic studies of the Holy Land and a window into the artistic traditions used to document one of the most significant maps of the ancient world.

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Minor soiling and foxing, but about excellent.

References

A. W. Dilke and the editors, “Cartography in the Byzantine Empire,” in The History of Cartography, Volume One: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe in the Meditteranean, pp. 265-265 and plates 7-8. Herbert Donner, The Mosaic Map of Madaba: An Introductory Guide (Kampen, The Netherlands: Kok Pharos Publishing, 1992). Yannis Meimaris, “The Discovery of the Madaba Mosaic Map. Mythology and Reality” (Originally published in Michele Piccirillo and Eugenio Alliata, eds., The Madaba Map Centenary, 1897-1997… Proceedings of the International Conferences Held in Amman, 7-9 April 1997 but now available on line.)