Münster’s Upside-Down Map of Europe.

Europa das ein drittheil der Erden nach gelegenheit unsern Zeiten.

Out of stock

Description

A Brilliant Synthesis of Classical and Contemporary Geography.

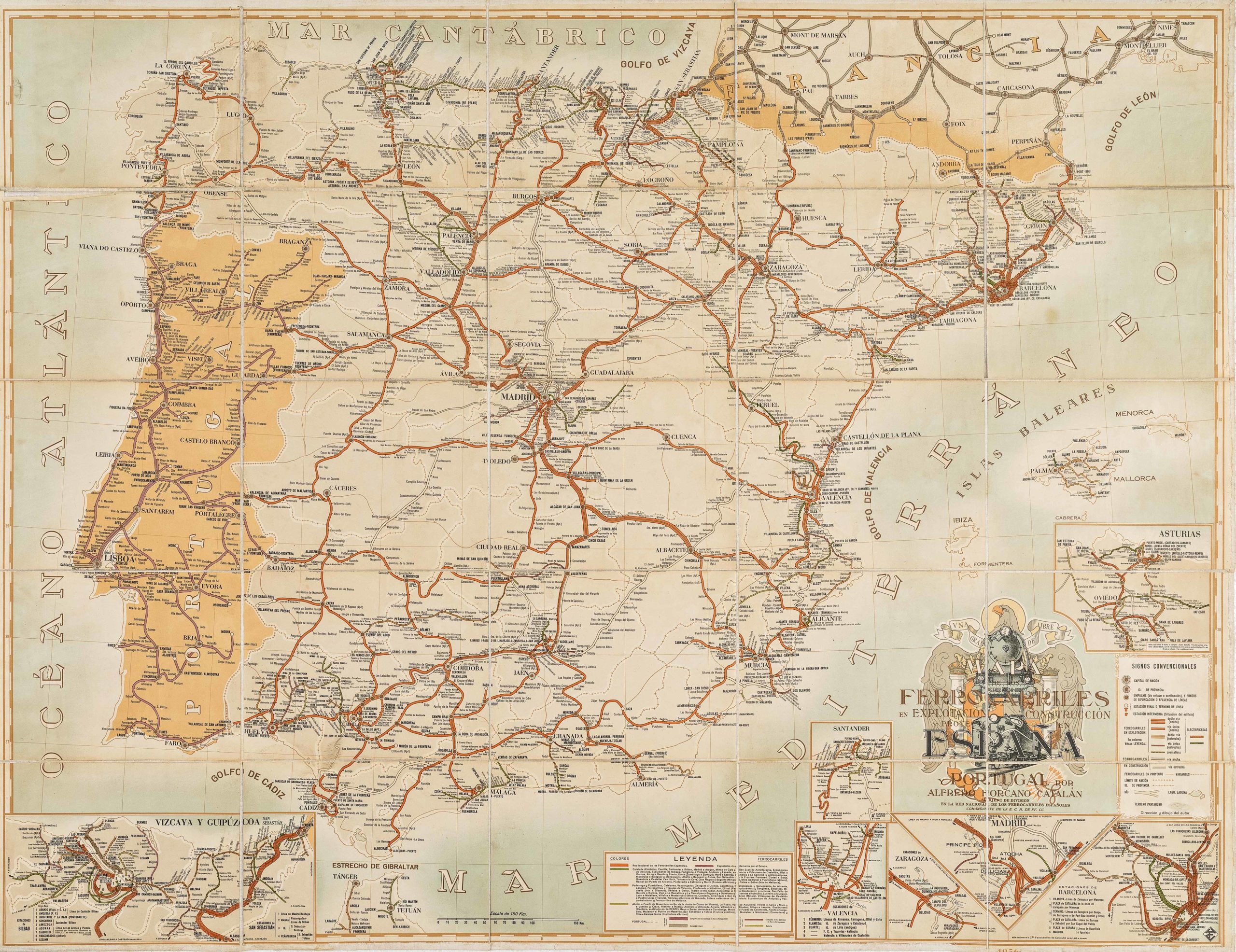

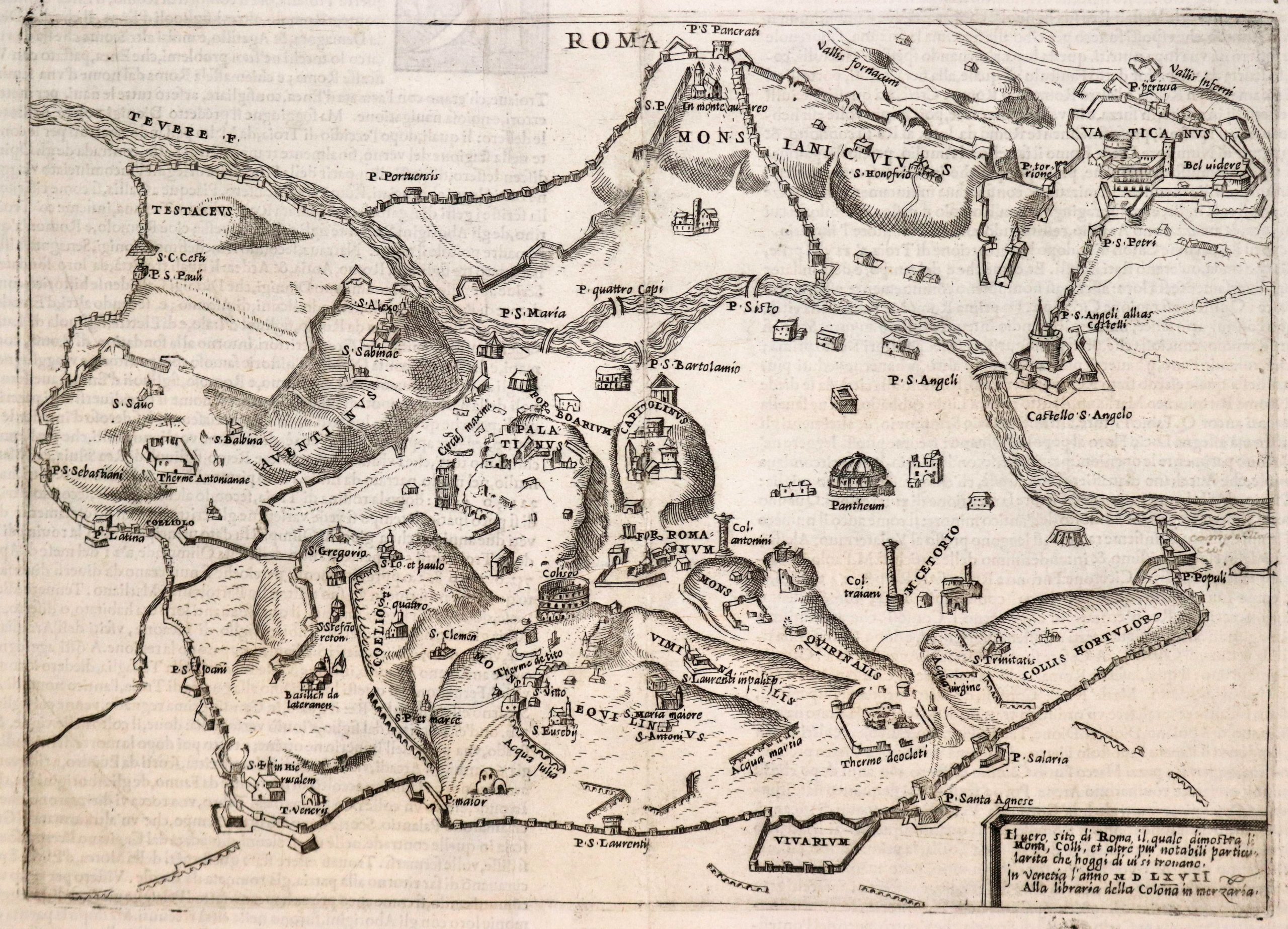

Sebastian Münster’s map of Europe is a landmark achievement in 16th-century cartography. The present woodcut map was published in a German edition of Cosmographia Universalis in Basel in 1567.

This celebrated map is particularly notable for its unconventional orientation, with south positioned at the top. This departure from traditional Ptolemaic cartography highlights Münster’s innovative approach. While earlier examples of southward-oriented maps do exist—such as Fra Mauro’s 15th-century world map—they were based on different conceptual frameworks.

The map encompasses most of Europe and adjacent regions. In the west, it includes Spain and part of Ireland, while the eastern extents reach the Black Sea, Bulgaria, Moldavia, and Livonia. To the south, Münster depicts the African coastline near Gibraltar and the island of Sicily. Meanwhile, the northern edges of the British Isles, Denmark, and Sweden are truncated, emphasizing Münster’s focus on central and southern Europe.

Münster’s cartographic details include major rivers such as the Danube, pictorial mountain ranges, and extensive forests, all depicted with intricate woodcut artistry. His use of regional names and city labels provides valuable insight into the toponymy of the 16th century.

Beyond its geographical accuracy, this map reflects the cultural and intellectual vibrancy of the Renaissance. Forests, rivers, and mountain ranges are not merely decorative but serve as significant geographic markers, illustrating the interconnectedness of Europe’s landscapes.

A particularly striking feature is the large sailing ship positioned in the Bay of Biscay, off the coast of Spain. This decorative element not only enhances the map’s visual appeal but also symbolizes Europe’s growing maritime dominance and the increasing importance of sea routes in the 16th century. The artistic craftsmanship of the woodcut complements its geographical precision, making it both a functional map and a work of Renaissance art.

The Fusion of Classical and Renaissance Thought

Münster’s work represents a remarkable synthesis of classical traditions and Renaissance innovations. While he was influenced by Claudius Ptolemy, the 2nd-century Greek cartographer, Münster incorporated modern geographical data and new discoveries into his maps, bridging the gap between ancient geography and contemporary exploration.

His emphasis on depicting modern cities alongside their ancient names highlights the Renaissance fascination with antiquity. It also served a practical purpose, helping 16th-century readers understand the historical evolution of European geography.

The southward orientation of the map—often perceived as unconventional by modern viewers—was a deliberate choice. It reflects Münster’s reliance on German regional maps designed for use with solar compasses. This orientation not only underscores the map’s German origins but also aligns with Münster’s broader mission: to make geography accessible and comprehensible to a wide audience rather than limiting it to academic scholars.

By presenting Europe from this perspective, Münster subtly emphasizes the centrality of Germany within his cartographic vision, both geographically and intellectually. This focus aligns with his broader contributions to cartography, making his maps indispensable tools for 16th-century scholars and travelers alike.

Census

The present map comes from a German edition of Münster’s Cosmographia Universalis, published in Basel in 1567. This monumental geographical and cosmological work succeeded Münster’s earlier Geographia.

First published in 1540, Münster’s map of Europe underwent multiple iterations. It was included in all editions of Geographia until 1552 before becoming a central feature of Cosmographia. The title of the map varied across editions, reflecting its evolving nature.

The German edition of Cosmographia played a crucial role in expanding Münster’s influence. Unlike Geographia, which was published exclusively in Latin, Cosmographia appeared in German, Latin, French, and Italian, making it accessible to a broader European audience.

By 1567, the printing block for this map exhibited minor signs of wear, including small cracks, attesting to its frequent use and enduring popularity.

This map stands as one of the earliest modern depictions of Europe, offering a unique blend of Renaissance scholarship and artistic craftsmanship. It remains the only widely accessible derivative of Martin Waldseemüller’s highly rare 1511 Carta Itineraria Europae. Münster’s innovative approach ensured that his maps remained essential references, capturing both the intellectual currents and geographical knowledge of the Renaissance era.

Cartographer(s):

Sebastian Münster (1488-1552) was a cosmographer and professor of Hebrew who taught at Tübingen, Heidelberg, and Basel. He settled in Basel in 1529 and died there, of the plague, in 1552. Münster was a networking specialist and stood at the center of a large network of scholars from whom he obtained geographic descriptions, maps, and directions.

As a young man, Münster joined the Franciscan order, in which he became a priest. He studied geography at Tübingen, graduating in 1518. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Basel for the first time, where he published a Hebrew grammar, one of the first books in Hebrew published in Germany. In 1521, Münster moved to Heidelberg, where he continued to publish Hebrew texts and the first German books in Aramaic. After converting to Protestantism in 1529, he took over the chair of Hebrew at Basel, where he published his main Hebrew work, a two-volume Old Testament with a Latin translation.

Münster published his first known map, a map of Germany, in 1525. Three years later, he released a treatise on sundials. But it would not be until 1540 that he published his first cartographic tour de force: the Geographia universalis vetus et nova, an updated edition of Ptolemy’s Geography. In addition to the Ptolemaic maps, Münster added 21 modern maps. Among Münster’s innovations was the inclusion of map for each continent, a concept that would influence Abraham Ortelius and other early atlas makers in the decades to come. The Geographia was reprinted in 1542, 1545, and 1552.

Münster’s masterpiece was nevertheless his Cosmographia universalis. First published in 1544, the book was reissued in at least 35 editions by 1628. It was the first German-language description of the world and contained 471 woodcuts and 26 maps over six volumes. The Cosmographia was widely used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and many of its maps were adopted and modified over time, making Münster an influential cornerstone of geographical thought for generations.

Condition Description

Hand color. Visible repairs, as seen on the image. Overall nice.

References

![[Map of Steamship Routes and the Railways and Post Roads of the Russian Empire]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NL-00827_Thumbnail-300x300.jpg)

![[Map of Steamship Routes and the Railways and Post Roads of the Russian Empire]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NL-00827-scaled.jpg)

![[Map of Steamship Routes and the Railways and Post Roads of the Russian Empire]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/NL-00827-scaled-300x300.jpg)