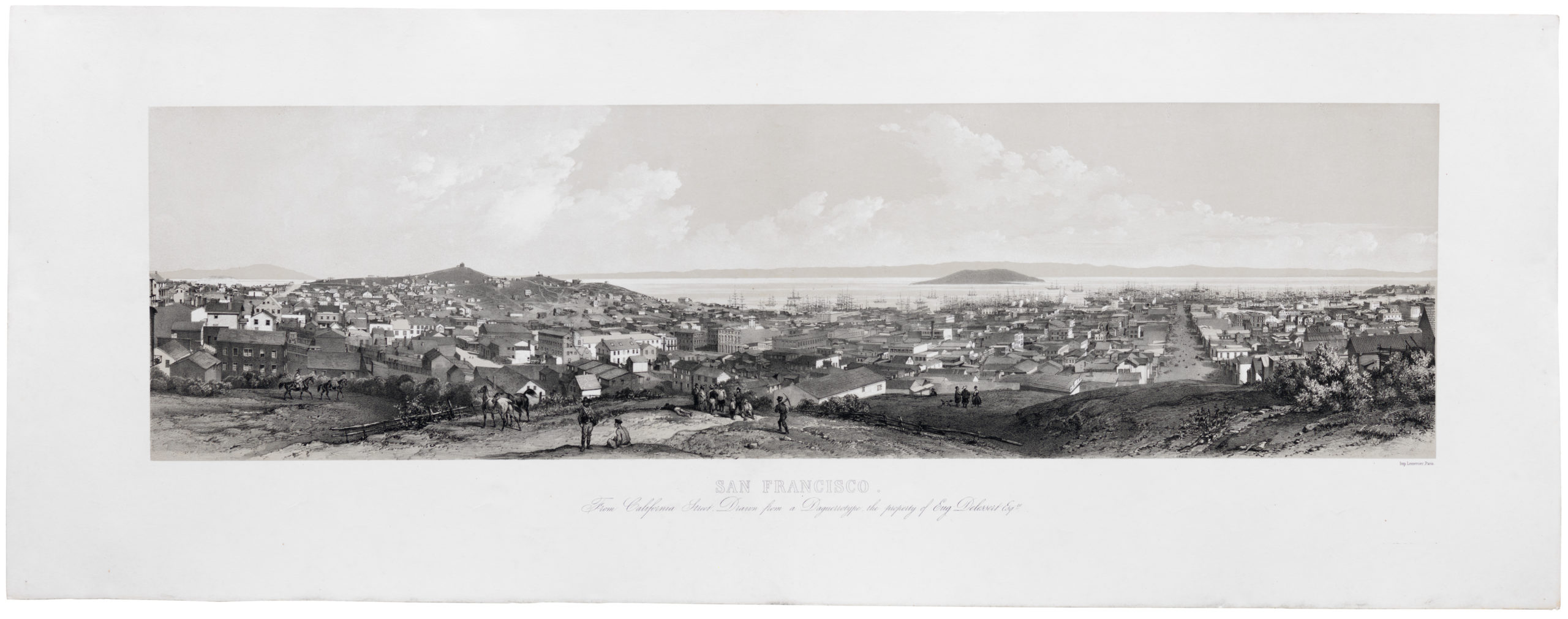

A snapshot in time for San Francisco’s Marina District: a stunning full panoramic view of the 1915 Panama–Pacific International World’s Fair.

Panama-Pacific International Exposition Panorama Photograph 1915.

Out of stock

Description

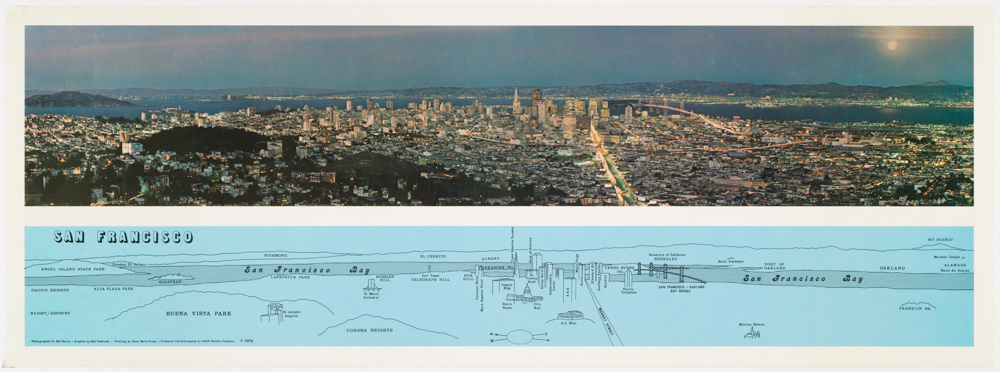

This gorgeous panoramic photograph of San Francisco was taken in association with the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a World Fair hosted by San Francisco throughout most of 1915 (Feb 20th – Dec 4th). The official occasion for the fair was the formal opening of the Panama Canal in July of that year; an incredible feat of engineering that was celebrated worldwide. The fair was nevertheless also seen as an ideal opportunity to showcase the city’s recovery after the horrendous devastation and mayhem caused by the great earthquake of 1906.

The panorama was issued by the Cardinell-Vincent Company and is a high resolution and strongly contrasted sepia photograph, which measures an impressive 45 by 9.15 inches (114 x 23 cm). The image underscores the ambition to cast San Francisco in a modern and monumental light and tells the story of the city’s remarkable turnaround less than a decade after the devastating earthquake of 1906.

The photo depicts a roughly one-mile stretch from Lyon Street in the west to Laguna Street in the east. The view offered is across Pacific Heights, Cow Hollow, and the Marina District, with San Francisco Bay, Alcatraz, Angel Island, Sausalito, and the Marin Headlands as a backdrop. There is no doubt that the photograph was designed specifically for the Panama exposition. In addition to it having been noted by the photographer at the bottom of the photo, the image covers precisely the 636-acre stretch that had been allocated to the construction of these magnificent fair grounds. It includes all of the exposition’s important landmarks, as well as many of the city’s well-known features. And because the staging of the exposition had as a subsidiary goal to demonstrate San Francisco’s dynamism to the world, the photographer seems to have been intent on capturing history and modernity in a single solemn image.

Moving from west to east, a number of buildings and urban features are worthy of note. Poignantly, the western fringe of the photo starts at the Golden Gate, the Pacific gateway that made San Francisco. Included in the western fringe we see the most famous and longest inhabited part of the promontory in the form of Fort Point fronting the Presidio. This was the original military encampment built here long before any notion of a city was in play, but controlling the point was crucial for trade and transport purposes. It was the gradual amalgamation of the Presidio area with the settlement growing out of Mission Dolores further south that shaped the city of San Francisco during the 19th century. In the photo, one can even see the Life Guard Wharf extending into the bay from what today is Crissy Field.

As with the famous world fairs of Chicago (1893) and St Louis (1904), the Panama-Pacific International Exposition saw the construction of a range of pavilion buildings by the participating parties, which included foreign countries as well as individual American States. The construction of architecture and infrastructure was an important concomitant to selecting the venues for these massive events. Just like the 1893 World Fair in Chicago symbolized the culmination of recovery from the devastating Chicago Fire of 1871, so too the Panama-Pacific Exposition constituted an opportunity for San Francisco to regain its full glory following the 1906 earthquake. We are in other One of the international buildings clearly visible is the elongated dark tower of the Norwegian Pavilion, most of which was modeled on a traditional Norwegian Manor House, tower and all. As an independent nation, Norway was no more than a decade old, yet its people had been immigrating to America for generations. Continuing east, into the more densely built up area east of the original Letterman Army Hospital, we find an increasing number of both national and international representations. Among these are the pavilions from Greece, Australia, and France, the latter of which was a three-quarters scale version of the Palais de la Légion d’honneur in Paris. While the original building no longer exists, in the early 1920s, Alma de Bretteville Spreckles funded the full-size replica that today is the Legion of Honor Museum in Lincoln Park. Moving further east, we come across the first State Buildings, including the Kansas, Iowa, Massachusetts and Washington Buildings. These in turn lie almost shoulder-to-shoulder with the Spanish-American pavilions of Cuba and Bolivia.

In the center of the image, a number of monumental domed and towered buildings dominate the view. The easternmost dome, which is fronted and reared by colonnades, is the rotunda of the still extant Palace of Fine Arts. This spectacular complex, modeled on the great palaces of Antiquity, was built specifically for the Panama-Pacific Exposition. It was designed by American architect Bernard Maybeck as an area of tranquility in the heart of the exposition, and was funded by the city of San Francisco. It was fronted by an artificial lagoon also visible in the photograph and is one of only a handful of buildings from the exposition that remain standing.

The most visually impressive building in this cluster is the great glass dome of the Horticulture Palace, with its exhibition halls stretched out to the west in front of it. Immediately behind the great glass dome we see two flatter domes, executed in a style emulating Late Roman architecture, which constitute the palaces of Education and Social Economy to the west and the Food Products Palace to the east. Across the Bay, immediately behind these domes, we see Sausalito and the entry into Richardson Bay. Immediately east of the Horticulture Palace dome, a large central plaza constitutes the heart of the exposition area. This open space, known then as the Avenue of Palms (present-day Bay St.), was actually modeled on the great Persian cities such as Isfahan or Tehran, which were built around a central Royal square or maydan. Like in Persia, the cities most important structures flank this open space, on what today constitutes the area stretching south from Bay Street, across Chestnut Street, and to Lombard Street along its southern flank.

Most prominent on the plaza is the Tower of Jewels, a 435-foot structure covered in polychromatic glass crystals (novagems) and rising imposingly above the rest of the cityscape, with the Bay as its backdrop. The opening ceremony was held on the monumental staircase fronting it, and the large central tower is flanked on each side by an enormous building capped by a central dome. These were known as the ‘Liberal Arts Palace’ (west) and the ‘Manufacturers Palace’ (east). Both opened onto the central plaza by means of large salient gates placed symmetrically on either side of the tower. In the courtyards of these buildings, one can see the colossal elevated statues entitled ‘Nations of the West’ and ‘Nations of the East’ respectively.

Just as the large glass cupola of the Horticultural Palace dominates the western flank of the great plaza, an equally impressive dome adorns its western flank. This spectacular dome and its large front-window belong to the great Festival Hall, where most of the formal celebrations were held.

Since very few of the buildings made for the exposition have survived, it can be difficult to orient the image properly according to today’s urban layout. Nevertheless, in addition to the many buildings discussed above, a number of still extant streets are visible in the image as well.

Chestnut Street constitutes the center of what was once the central plaza and is flanked by Bay Street on the north and what today constitutes the busy Lombard Street to the south. Intersecting with Lombard Street from the south, one has a clear view of Divisadero Street, whereas its parallels — Scott Street, Pierce Street and Steiner Street — are only visible by following the rooftops of the buildings lining them. In the bottom right corner of the image, there is a glimpse of Greenwich Street and in the middle of the western edge of the photo, careful inspection of the rooftops reveals the outlines of Laguna Street and Buchanan Street, behind which one can discern the pagoda tower of the Chinese Theater.

Background

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) may have formally been in celebration of the conclusion of the Panama Canal, but it was also part of a longer tradition of hosting World Fairs in order to promote business and celebrate progress. We have already covered how this exposition served to underline the recovery of San Francisco after the devastation of the 1906 earthquake, and how this strategy was not necessarily a new one. In addition to the magnificent neighborhood constructed for the occasion, it is nevertheless interesting to note some of the events and showcases set up specifically for this occasion. One of the big magnets was the actual Liberty Bell, which had been transported from Pennsylvania by railroad across the continent to San Francisco. In addition to allowing visitors of the fair to see one of the most prized American relics, it also underscored the incredible achievement that was the transcontinental railroad and demonstrated, in a very tangible fashion, its potential for transport. Another great innovation was a telephone line that ran between San Francisco and New York. The nature of the setup supposedly allowed people across the nation to hear, in real time, the roar of the Pacific Ocean.

The PPIE was a hugely important event for the development of San Francisco. In many ways it succeeded far beyond its ambitions in conveying to America, and the world, a story of recovery and dynamic progress. It is hard to say what the exact repercussions of the fair were, but in the decade following it, San Francisco enjoyed another boom in industry and commerce. The impact of the fair as a showcase for American ingenuity was beyond debate and the exposition was commemorated in booklets, maps, and even $50 octagonal gold coins. In 2015, a series of coordinated events celebrated the 100th anniversary of the exposition. As part of this, a feature film was produced to tell the story (When the World Came to San Francisco).

Cartographer(s):

The Cardinell-Vincent Company was the official photographer of the Panama Pacific International Exposition. The company employed over 150 employees under the direction of president John D. Cardinell. Among their briefs was setting up photographic galleries on the grounds and organizing the enterprise into different departments. The company was disbanded upon the completion of the exposition.

Cardinell-Vincent Co. produced a range of official photographs, including several panoramic views. A number of these photos still exist in various public and private collections, including the de Young Fine Arts Museum in San Francisco.

Condition Description

Sharp sepia image with strong contrast. The left and right edges of the photo have sustained light damage from the original framing, and the exposure from framing has caused light discolorations. Overall, however, the photograph is nevertheless in very good condition.

References

Special thanks to Nick Wright for his annotations.