Plan of the Old City of Jerusalem by the Ottoman city’s official architect and engineer.

Plan De Jerusalem Ancienne & Moderne

Out of stock

Description

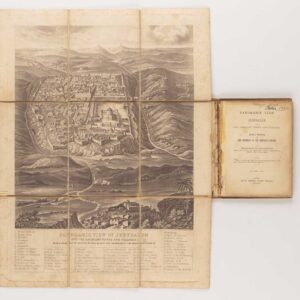

A unique and precise architectural plan of mid 19th century Jerusalem that evokes a romantic period in the city’s history. The map is finely engraved and offers a highly detailed layout of the Old City, in which Jerusalem’s famous sites are clearly identifiable. It was drafted by Ermete Pierotti, who in 1858 was appointed the city’s chief architect and engineer by the Ottoman governor of Jerusalem.

The map is a true gem: a reflection of Pierotti’s unique position and experience in life and his skill and dedication as a draughtsman. Within five years of this publication, the first systematic Ordnance Surveys by the British Army were published, lifting the mapping of Jerusalem and Palestine to a whole new level of scientific accuracy. In this context, Pierotti’s map is a forerunner to a subsequent era, one that leaves little to be left desired regarding accuracy and beauty. It is quite possibly one of the finest Victorian charts of Jerusalem ever made.

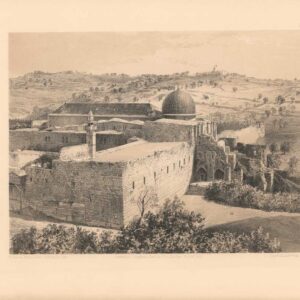

Being the eternal city, many parts of the built-up area have changed little since Pierotti first drafted this plan. Along both sides of the map, we find no less than 18 insets of historical sites within the city. These are proper architectural plans and include iconic mosques and churches such as the al-Aqsa, the Dome of the Rock (Mosquée de Omar), and the Holy Sepulchre (Temple de la Résurrection), but also more esoteric sites such as the rock-cut Judges’, Kings’, or Prophets’ tombs. Throughout the urban plan, essential landmarks of historical or religious significance have been marked and linked to several legends on the map. The thematic legends refer to places of historical importance to the three Abrahamic religions. They include newer places of interest, such as the schools, churches, and hospitals of the Latin Patriarchate, Coptic khans and convents, and European consulates and business offices.

In general, the plan contains a number of tables and legends set around the edges of the main map. These remain unconnected to the inset plans that flank the city map on either side. In addition to the list of ‘Modern Jerusalem’ noted above, we find several legends referring to specific places on the greater urban plan. Moving counter-clockwise around the central map, these include: a list of important locations within the Haram al-Sharif (i.e. the sacred Muslim precinct that includes the Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock); triple scale bars showing distances in meters, stades, and yards respectively; two boxes identifying points of interest outside the city walls, as well as a population chart subdividing Jerusalem’s inhabitants by religion and ethnic origin in the lower right-hand corner. In the upper left corner, we find a table defining the cartographic symbols used on the map (Signes conventionels), above which there are numbered legends identifying ancient points of interest outside the city walls, inside the city walls, and on the Via Dolorosa specifically (Christ’s route through the city prior to his crucifixion).

One might argue that this map constitutes one of the best examples of the early tourist maps produced in the Victorian Age of adventure. In fact, a traveler or pilgrim equipped with this chart would have found it relatively easy to navigate efficiently both in and around the Old City, something that can still be taxing to this day. On the plan, we recognize numerous significant Jerusalem landmarks. We have already mentioned the Holy Sepulchre and Haram al-Sharif, but just as visible, we see the old city gates (Damascus, Jaffa, Herod, and Sion), the Mamluk fortress, and the Roman-period Jewish neighborhood of Bezetha, famously known from the accounts of Flavius Josephus.

We find all the essential topographic toponymy outside the city walls clearly noted. Despite some of these places having immense symbolic significance, identifying historical sites in and around Old Jerusalem can still be very difficult for those not intimately familiar with the urban landscape. Ancient Jewish place names known from the Torah and Bible – such as the Valleys of Gehenna and Gihon, or the heights of Mount Akra, Scopus, Ophel, and the Mount of Olives, are all visible on the map. Similarly, we find areas that remain hotly contended today, such as the Valley of Silwan, which Palestinians hold as an important part of their historical claim to the Holy City.

The age-old multi-religious focus on the city and the shifting tides of history are also well-represented in other ways on this incredible map. One could look, for example, at the population chart, which identifies no less than 17 distinct groups in a population of just over 20,000. Another way to see the cosmopolitanism of Jerusalem is by looking at the many cemeteries found outside the city walls. These include modern and ancient cemeteries for Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike and have more dedicated burial spaces for the Ottoman and Armenian populations. But the most telling element is perhaps the ubiquitous presence – both past and current – of non-indigenous groups that have made their mark on this historic landscape.

Census

This version of Ermete Pierotti’s map was published in a single edition printed with Kaeppelin & Cie in Paris in 1860. It is scarce on the market, commanding increasingly higher prices.

Institutional copies are held in the University of Oxford (OCLC cat. 557824978), in the Zentralbibliothek in Zürich (OCLC cat. 52345220), The Jewish Theological Seminary in New York (ibid.), Princeton University Library (ibid.), and the Flora Lamson Hewlett Library of the Graduate Theological Union of Berkeley, California (ibid.).

Cartographer(s):

Ermete Pierotti (1820-1880) was the oldest of nine siblings in a family from Pontardeto in Pieve Fosciana (the family built the Palazzo Pierotti, which has served as the town hall since 1877). Pierotti worked as a military engineer in Genoa and later served as a captain in the Engineering Corps of the Sardinian King. In 1849, he was accused of desertion and the theft of 3596 lire from the troop’s treasury, which resulted in a dishonorable discharge from the army. Pierotti then traveled to Jerusalem and Egypt, where he worked as an engineer. In Egypt, he discovered the foundations of the Alexandria Library while laying the foundations for a Greek church, but it was in Jerusalem that he would put his surveying and engineering skills to work.

Pierotti arrived in Jerusalem in 1854 as a consultant for the Franciscan Order, which had custody of many of the Christian holy sites in the city. During his time there, Pierotti was involved in the restoration of the Crusader Era Church of St. Anne, located in the Old City near the Pool of Bethesda. Working with Ottoman engineer Assad Effendi, he later contributed to the restoration of the Qanat as-Sabil, the main aqueduct that supplied Jerusalem with water, which involved repairing the aqueduct’s channels and cisterns. Other building projects included work on the Temple Mount itself and the construction of both the Austrian Hospice and the so-called Alexanderhof (HQ of the Kaiserlichen Orthodoxen Palästina-Gesellschaft) in the Christian Quarter of the Old City. And finally, he helped design the road from Jaffa to Jerusalem, a significant engineering feat at the time.

Pierotti became interested in the city’s history and archeology during his time in Jerusalem. He conducted several excavations in the Old City. He discovered several important artifacts, including an inscription in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre that proved the existence of a church on the site during the Byzantine period. Pierotti’s work in Jerusalem earned him a reputation as a skilled engineer and pioneering archeologist. He became known for his attention to detail and ability to work under challenging conditions. In addition to his many projects, Pierotti’s legacy consists of publishing his magnum opus: Jerusalem Explored. A Description of the Ancient and Modern City (1864), which included an entire volume of lithographed plates based on Pierotti’s plans and converted photographs.

Despite his many successes, Pierotti’s work and position annoyed the British, who increasingly sought to establish a scientific presence in the Holy City, if not a colonial one. When competition arose between Pierotti and Captain Charles Wilson’s team of English Royal Engineers conducting the first Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem and surroundings in 1864, Pierotti’s reputation was deliberately tarnished by the disclosure of his criminal past, and for the rest of his life, he struggled to regain recognition for his achievements.

Condition Description

Folding map on strong original backing.

References

![Jerusalem [Old City].](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NL-01944_thumbnail-300x300.jpg)