A work of early political satire produced at the peak of Voltaire’s popularity.

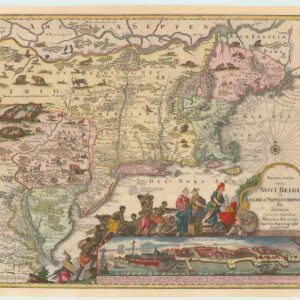

Accurata delineatio celeberrimae Regionis Ludovicianae vel Gallice Louisiane ol. Canadae et Floridae Adpellatione in Septemtrionali America Descriptae quae Hodie Nomine Fluminis Mississippi vel St. Louis

Out of stock

Description

Matthäus Seutter’s map of colonial America encapsulates predominant trains of thought in the early to mid-18th century. On the one hand, Seutter wanted his map to embody the pioneer sentiment that carried much of the early colonialization of this North America. On the other hand, he was compiling a chart highly attuned to the latest philosophical discourses in Paris.

The map is marvelously detailed, despite depicting an enormous area. It was primarily created for the French market, as can be seen in the language and perspectives applied throughout the map. Different European claims are delineated using thick lines and stark colors, and the toponymy is labeled according to what one might call a Francophile view. The English colonies along the coast stand out clearly in yellow, while New France is depicted in a softer pink. Greater Louisiana, to which the French also laid claim, is shown in vivid green, whereas the Spanish territories of New Spain and New Mexico have been left uncolored, reflecting Spain’s reduced role on the global stage.

The map deliberately highlights particular swathes of North America. Exciting frontiers such as the Mississippi Valley constituted important spheres of interest and investment for the French, and have consequently been supplied with as much detail as was available. There is a large inset of the Louisiana coastline west of Pensacola Bay (Baye de Ascension) in the upper left corner of the map. The inset map includes the deltas of both the Mississippi and Mobile River, as well as the many islands fronting the coast and numerous forts, villages, and Native American settlements throughout the littoral. Another slightly more domesticated frontier was the Great Lakes area, which falls entirely within Nouvelle France’s borders.

The map has many interesting features telling for the time in which it was produced. For example, in the lower-left corner, we find a fascinating scale showing the amount of time (measured in segments of one hundred hours on the road) traveling a certain distance on the map might take. This scale seems an odd inclusion for a map at this scale and in this era, but its real purpose is not to convey a concrete distance so much as to lend the viewer the impression of the vastness of this new continent. Beneath this amusing little detail, we find the latitudinal and longitudinal positions of major cities, including Quebec, Port Royal, Bristol, and Jamestown.

A most famous cartouche

The most fantastic feature of this map is nevertheless the elaborate cartouche, which Matthäus Seutter himself designed. While the composition leaves little to be desired artistically, what makes it great is the blatant satire and explicit allegorical references to a particular financial calamity. The Mississippi Bubble of 1719 was essentially the collapse of a fiat banking system conceived by Scottish banker John Law. Law had won enormous credibility through his financial backing of the ‘Compagnie Francoise Occident‘ – a trading company set up to sustain the debts of the French King, Louis XIV – and his new bank in Louisiana attracted such a flurry of highly speculative investments that it eventually caused the first financial market collapse in American history (more on this in the context section below).

The cartouche refers to these events by showing Fortuna – the Roman goddess of chance and luck, but in this case also a personification of the Mississippi River – pouring gold and jewels onto a crowd of investors below. While some seem to be eagerly buying new shares, others are clearly lamenting their losses and committing suicide in desperation. That this is indeed the cause is made unmistakable by the angel above them, holding an empty purse. The precarious nature of Fortuna’s wealth is indeed reflected in her very image, standing as she does on a flimsy winged bubble. The bubble theme continues in the scene below, where two winged cherubs use a printing press to produce new shares from nothing while two unwinged lads blow soap bubbles in the air.

Even though the map is interesting as a pro-French depiction of early colonial America, Seutter’s willingness to engage in such an explicit satirical musing elevates this map above its contemporaries. Seutter compiled and published this map in the lifetime of the first French satirists like Voltaire. Humorist musing over the shortcomings of politicians, or the greed of bankers, is a true mark of the Enlightenment Age in which Seutter lived. This was an age in which old taboos were abandoned, and previously untouchable groups like the aristocracy could be freely ridiculed. As such, Seutter’s chart is a highly democratic map, one designed to push the boundaries of free speech and make its viewers aware of their right (and obligation) to speak out against injustice and folly.

Context is everything: John Law and the Mississippi Bubble

The Mississippi Bubble hinged on John Law’s Companie des Indes (also known as the Mississippi Company), a French trading company set up to invest in the resources of Louisiana and the Mississippi River.

The affair was essentially a process from August 1719 to May 1720, driven by inflation and highly speculative investment schemes. It was anchored in the French economy, which at the time was in tatters. In 1715, Louis XIV died and left the Treasury in a sorry state. The regent turned to John Law, who had set up the Compagnie Francoise Occident during Louis XIV’s financial struggles to re-inflate the French economy. Law’s response to the crisis was to propose that instead of coinage, the value of which fluctuated dramatically, the Royal Bank should begin issuing guaranteed notes. This transition to paper currency helped stabilize the French economy for a time and elevated Law to the highest circles of French society. In 1717, Law used his position and favor to win a monopoly on trading rights with the French colonies in Louisiana. Law then traded shares of his Mississippi Company in for French debt, gradually transferring much of France’s debt to his company.

Under normal circumstances, such a model was hardly sustainable, for the trade generated by Louisiana was nowhere near enough to cover French debts. But Law and his associates promised enormous returns on investments, which naturally sparked a huge interest. Law had, after all, set up two successful financial schemes in the past. With only 50,000 shares on offer and significantly higher demand, share prices soared. And still being in the initial throngs of excitement about creating a paper-based currency, the French government ran the presses day and night, adding inflationary dynamics to the already exorbitant prices.

During the course of the scheme, some people made enormous profits, and initially, their stories added more fuel to the fire. But in May of 1720, the bubble finally burst when the Banque Royale had to formally admit that they could not honor the full amount of paper currency issued. A plan was put in place to gradually depreciate the shares of the Mississippi Company to half of their nominal value, but by the end of the year, the claims had become entirely worthless, and Law had disappeared.

Cartographer(s):

Matthäus Seutter (1678-1757) was one of the most important and prolific German map publishers of the 18th century. As a young man, he was an eminent engraver who had been trained under the great Johann Baptist Homann in Nürnberg. In the mid-1720s, he moved to his hometown of Augsburg and set up his own printing and publishing house, specializing in maps. His skill as a cartographer was soon noticed in higher circles, and in 1732 Seutter was appointed Imperial Geographer to Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI. The appointment came after his most famous cartographic publication, the two-volume Atlas Novus Sive Tabulae Geographicae, from 1730.

Like many of his contemporaries, Seutter drew heavily on other mapmakers when compiling his charts. Among his primary sources were the maps of his mentor Homann and the great French cartographers Guillaume Delisle and Nicolas de Fer. When Seutter died in 1757, his son-in-law, Tobias Conrad Lotter, took over the firm.

Condition Description

Excellent.

References