Eddy’s 1849 map — One of the earliest obtainable maps of San Francisco.

Official Map of San Francisco, Compiled From The Field Notes of the Official Re-Survey made by William M. Eddy, Surveyor of the Town of San Francisco, California, 1849.

Out of stock

Description

Important early map of San Francisco — the earliest obtainable map of the city — a wonderful early document of Gold Rush California.

For a more detailed look at this map, please see: https://youtu.be/GWOtgXJjCsQ

This was the first widely-distributed map of the city of San Francisco, published at a momentous time in the history of the Bay Area. In July of 1846, as part of the broader Mexican-American War, Captain Montgomery of the sloop-of-war Portsmouth landed with seventy men at the Mexican pueblo of Yerba Buena, at the foot of Clay Street, and march up to the main plaza. There was no defending force and in fact no Mexican officials present from which to accept surrender. The American flag was raised on a pole in front of the customs house, and the town was now a de facto part of the United States.

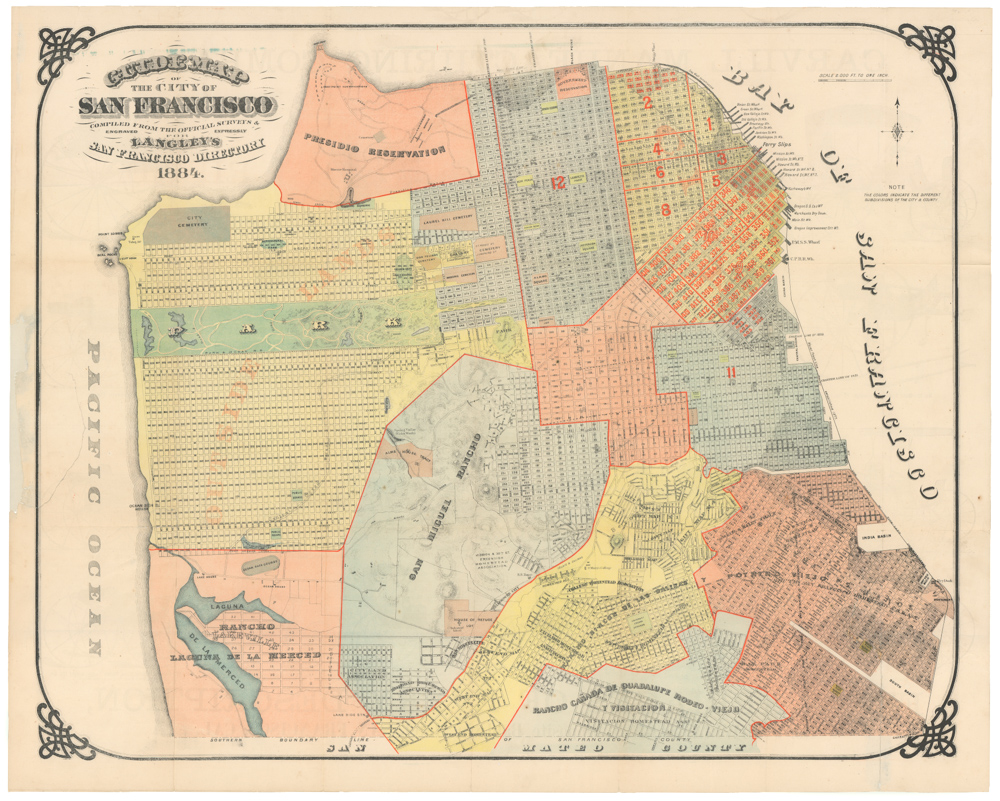

Six months later, on January 23, 1847, Chief Magistrate Washington A. Bartlett announced an ordinance officially renaming Yerba Buena as San Francisco. At the same time, Bartlett hired accomplished surveyor Jasper O’Farrell to create in essence the first scientific map of the city, which at the time had a population under one thousand people. O’Farrell conducted his survey from about March to September of 1847, measuring distances with chains and establishing a grid of survey markers. O’Farrell sought to correct inaccuracies in the pre-existing 1839 plan of Yerba Buena drawn by Vioget, which was fairly rudimentary. He adjusted angles and extended the grid west to Leavenworth, north to Francisco, and south to Post. He also surveyed water lots in the bay to the east and created one of San Francisco’s most enduring urban features, Market Street, south of which he started a new grid with double-sized blocks (100 vara instead of 50 vara) and a different orientation based on the pre-existing Mission plank road.

This map is built on the foundation of the O’Farrell survey. But the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, and the resulting boom in population (which by mid-1849 had reached an estimated five thousand people), made it necessary to expand the existing grid. Furthermore, many of O’Farrell’s survey markers had been knocked over or removed. William Eddy, a young engineer from New York, was assigned the task of grid extension and resurvey. He planned the city west to Larkin street and south to Market, filling in gaps along the way, and expanded O’Farrell’s south of market 100 vara grid; we use the word ‘planned’ because much of the Eddy map is a reflection of future growth rather than a record of current occupation.

An essential aspect of Eddy’s mission was the creation of new water lots in Yerba Buena Cove, the sale of which provided badly needed revenue to the city. The result is seen on this map, which depicts the original waterline around Montgomery Street, with new lots and streets extending into the Bay. Eddy has also depicted the Central Wharf, which was approved in May 1849 and became San Francisco’s first “modern” wharf (now the site of the Ferry Building Marketplace and Golden Gate Ferry Terminal). The main problem with the waters here is that they are relatively shallow, and city merchants and politicians had quickly understood the need to develop the waterfront to accommodate the many arriving ships, first and foremost a wharf to facilitate the off-loading of goods. The wharf follows the same line as today’s Commercial Street.

Eddy’s map is a straightforward and effective, focused on streets and original lot numbers, with some features including Yerba Buena Cemetery (the site of today’s Civic Center), Fort Montgomery, and the the city’s original plaza, now named Portsmouth Square after Montgomery’s ship. The map also shows three small sections in outline color, corresponding to the grants to Señora Briones, the claim of the heirs of Col. J.A. King, and the claim of Señor Pana under a Mexican grant. These are a hint as to the complicated legal battles over land ownership that would be a dominant theme for decades to come.

The scope of the map is a reflection of the settlement landscape on the San Francisco Peninsula at the time of the Gold Rush. Besides the growing concentration of San Francisco itself, there existed two other settlements — one military and one civilian — both of which originated in the the Spanish period (1776-1822). To the northwest, at the mouth of the Golden Gate, was the concentration of soldiers that comprised El Presidio de San Francisco, with its promontory fort. This military settlement was positioned to monitor the movement of ships in and out of the Bay, and to guard against possible attacks from the north.

Further south was the civilian settlement, which had grown out of the old Mission San Francisco de Asís, popularly known as Mission Dolores after a nearby creek named Arroyo de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores, meaning “Our Lady of Sorrows Creek.” While the location of the Presidio had been chosen for strategic purposes, the the area of the Mission was a superior site for civilian life: it sat at the nexus of shallow creeks that allowed access to the Bay, was likely near a fresh water lagoon, and — as San Franciscans today can still attest — offers the best weather in the area.

Eddy began his survey in September of 1849 and filed the map at the nearest Federal District Court in Oregon City, Oregon, on February 1, 1850. A few months later San Francisco was officially incorporated and a few months after that California became a state.

Finally, another fascinating feature of this map is the so-called Laguna Survey, the enigmatic 26-lot survey in the upper left corner, oriented at an odd angle to the expanding axis of the city grid. Legal records suggest that the lots were designated by Thaddeus Leavenworth in 1847, and it is likely that O’Farrell carried out the survey work. The full back story to its inception has never been fully explained, but as a result of the enduring influence of Eddy’s map, the Laguna Survey remained a cartographic feature on maps of San Francisco for decades. Officially, the survey was rendered obsolete by the Van Ness Ordinance of 1855, but two remnants are found in San Francisco streets today: Blackstone Court off Franklin St. and Grenard Terrace, a short private street in Russian Hill. Its influence is also seen on this 1888 map, with a now gone East Van Ness: Map of the 41st Assembly District Showing its Election Precincts.

Publication information

The earliest available published maps of San Francisco were produced by county surveyor William Eddy. In the years 1849-51, Eddy’s The Official Map of San Francisco, Compiled from the Field Notes of the Official Re-Survey made by William M. Eddy was published in a variety of city reports. A similar version was published separately in 1851 with the title: Official Map of the city of San Francisco, full and complete to the present date. Compiled by Wm. M. Eddy, City Surveyor. January 15th, 1851. In the 1851 map, the title has been moved to the left side, and more of the area south of Market is shown. But the main difference between it and the earlier Eddy (what we call ‘Eddy Classic’) map is that the original shoreline has been colored red; for this reason, it is often referred to as the Red Line Map.

•1849 “Eddy Classic”: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4364s.la002357/

•1851 “Eddy Red Line”: https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~224271~5506363:Official-map-of-the-City-of-San-Fra

Cartographer(s):

William Eddy was born in New York and worked as an engineer on the state’s canals. He arrived in San Francisco in 1849 amidst the excitement of the Gold Rush and was appointed as a land surveyor.

Condition Description

Excellent.

References

Howes J248; cf Vogdes 231.

![[1906 EARTHQUAKE PANORAMA – FINANCIAL DISTRICT]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Screen-Shot-2023-02-06-at-6.55.56-PM-300x300.png)

![5-sheet set showing San Francisco’s post-1906 earthquake water supply [SF’s first fireboat!]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/NL-01375-sheet-4_thumbnail-scaled-300x300.jpg)

![5-sheet set showing San Francisco's post-1906 earthquake water supply [SF's first fireboat!]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/NL-01375-sheet-4_thumbnail-scaled.jpg)