Athanasius Kircher’s stunning chart of the Sun.

Schema corporis Solaris

Out of stock

Description

One of the first sun maps.

A hugely influential depiction that became the basis for future celestial cartographers.

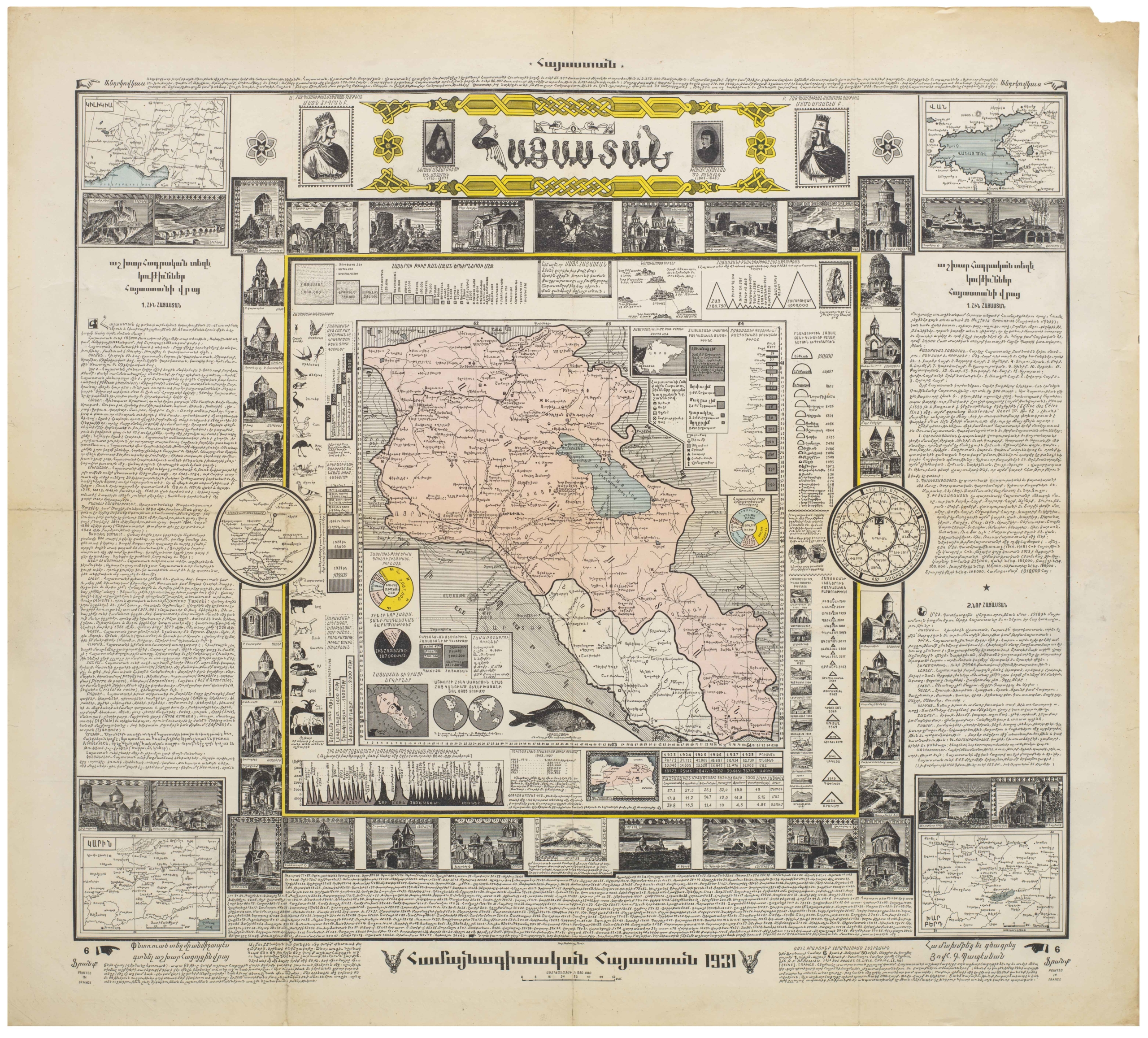

Athanasius Kircher’s chart of the Sun is one of the most extraordinary and fantastical maps to grow out of the cartographic craze that marked the transition from Renaissance to Enlightenment. It is a well-preserved hand-colored engraving from the first edition of Kircher’s iconic work on the subterranean world. The Mundus Subterranus was published by Jan Janssonius and Elizeum Weyerstraten in Amsterdam in 1664 and was the first scientific work that purported to describe the inner workings of the Earth (more on this in context section below).

The 12-book tome was brimming with diagrams and maps detailing the hitherto un-detailable. In this particular case, the title cartouche informs us that the rendition was based on a series of observations made by Kircher and his colleague, Christoph Scheiner, in Rome in 1635. However, there is much more to the story.

The map, which measures 47 x 40 cm (18.5 x 15.5 in), depicts the surface of the Sun, complete with ranges of great polar volcanoes, enormous craters, violent eruptions, and solar flares. Kircher’s observations of active volcanoes in Italy led him to speculate that the core of the Earth consisted of a burning mass and that volcanoes functioned as safety valves to release internal pressure. It must have been an intimidating image when published: a Jesuit scholar providing a scientific visualization of something that most people at the time associated with Hell. But this was never intended to be a religious image. By juxtaposing his studies of the Sun with new observations on the Earth’s geology and composition, Kircher was able to compile the first explanatory or scientific map of the Sun in history.

Kircher constructed the map in the same way as hemispherical maps of the Earth were at the time, with the northern (Borealis) pole at the top and the southern (Australis) pole at the bottom. A thin line runs between the two labeled points (Axis Globis Solaris), and a second line indicating the solar equator (Æquator Solaris) intersects it at the Sun’s center, essentially dividing it into quarters. Across the spherical plane, various features are labeled with capital letters, for which an explanatory legend in Latin is provided at the bottom of the map.

In addition to identifying the axial (FG) and equatorial (DE) meridians, Kircher’s chart distinguishes between the northern (BFC) and southern (HGI) polar circles. It delineates a great central band (BCHI) described as a ‘scorched region of the sun’ (Spacium Solis torridium). Within the sphere’s space, great burning craters are labeled ‘wells of light’ (A. Putei lucis). In contrast, great plumes of erupting steam are noted as the origin of ‘sun spots’ (evaprationes una et macularum origo).

Beautifully engraved and gorgeously embellished with hand color, this is a truly stunning depiction of a subject that, until Kircher, nobody had ever thought to document cartographically.

Context is Everything

Athanasius Kircher was one of the great polymaths of the 17th century. He was a contemporary of Galileo and possessed a similar curiosity and thirst for knowledge, although he remained in the good graces of the Church throughout his life. As a Jesuit priest and scholar, Kircher was a learned man who had leeway to conduct a range of important experiments and observations during his lifetime. His true awakening, however, came after a visit to southern Italy in 1637-38.

The volcanic activity he witnessed in Italy both fascinated and frightened Kircher to such an extent that he built his most famous work, a comprehensive survey of the subterranean world, on the observations made during this trip. He expanded these with earlier datasets and a plethora of wonderful explanatory illustrations and maps.

The Mundus Subterraneus marks the first serious effort to describe the physical makeup of the Earth, proposing theories (sometimes fantastical) within the fields of physics, geography, geology, and chemistry. Among the hypotheses that Kircher put forward in this work was the existence of a vast network of underground springs, reservoirs, and lakes. He was also the first to suggest that subterranean temperatures increase directly in proportion to depth.

In addition to speculating on the geological makeup of the Earth, the Mundus Subterraneus proposed the existence of underground rivers of fire and strange inhabitants in the planet’s interior. The book’s complexity was underlined by its endeavor to link the subterranean phenomena with observable features on the Earth’s surface (e.g. currents and meteorology), as well as with celestial phenomena like solar and lunar eclipses. Kircher then used established ideas about the Earth to create hypothetical depictions of the sun and the moon.

Kircher lived in a world where anything that could be mapped could be understood. Indeed, mapping often proved a vital part of the process that led to understanding. In the 17th century, such notions drove men to explore the Earth’s furthest and most inhospitable regions, just as it drove our author to lower himself into the crater of Vesuvius shortly after an eruption.

Cartographer(s):

Athanasius Kircher (1601-1680) was a Jesuit priest and scholar who gathered knowledge from around the world through Jesuit missionaries and disseminated it in a more compelling and effective form. In many ways, Kircher was one of the last great Renaissance thinkers. In addition to his explorations of the Earth’s interior, he conducted experiments using bioluminescence as a light source and was the first known maker of the Aeolian harp.

Kircher assembled one of the first natural history collections in the world, wrote more than forty books, and left over 2000 manuscripts behind. Within this oeuvre was a range of ground-breaking (and often highly speculative) maps, including the first depiction of the Pacific Ring of Fire and the first map to show oceanic currents on a global scale.

Condition Description

Repaired lower right corner, else excellent.

References

![[Political broadside] Solidarity with the People and Students of the DPR of Korea.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/NL-01603_thumbnail-1-300x300.jpg)

![[Political broadside] Solidarity with the People and Students of the DPR of Korea.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/NL-01603_thumbnail-scaled.jpg)

![[Political broadside] Solidarity with the People and Students of the DPR of Korea.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/NL-01603_thumbnail-scaled-300x300.jpg)