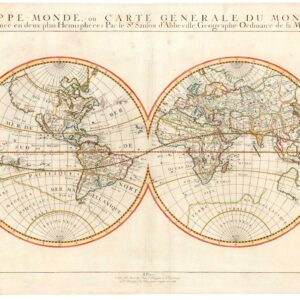

Justus Danckerts’ impressive 1680 double-hemisphere world map, with unique manuscript annotations listing ownership back to 1695.

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Tabula ex officina Iusti Dankerts Amstelodami

Out of stock

Description

This extraordinary chart by Dutch mapmaker Justus Danckerts demonstrates the pivotal role of Dutch explorers and mapmakers in the 17th century. As a full world map, the chart grants us an unfiltered insight into how some of the best mapmakers understood and organized the world they inhabited. A first state with vibrant original hand coloring, this map would once have stood in direct competition with the work of renowned cartographers such as Frederick de Wit, Jan Janssonius, and Willem and Joan Blaeu. In addition, this particular example has a remarkable set of manuscript annotations, which we discuss below.

The chart comprises an impressive double hemisphere map showing the Western and Eastern Hemispheres, respectively. As is often the case in 17th-century maps of the world, one of the most exciting features of the Western Hemisphere is the still un-plotted Northwest Pacific and America’s physical relationship with eastern Asia. Mapping this region had been at the forefront of expedition strategy since Magellan entered the Pacific Ocean in 1520 and was profoundly related to European powers’ desire to find new, unobstructed trade routes to East Asia. The paucity of firm knowledge of the American interior is also apparent, for example, in the open-ended Lake Superior and Lake Michigan. Depicting the Great Lakes in this manner constituted an emulation of the maps of Nicholas Sanson, who had resolved the lack of reliable knowledge on their western fringes with this model.

Another rather remarkable feature is the depiction of California as an island. Doing so was not an unusual feature in 17th-century maps, and some of the greatest compilers of the century applied this perception in their charts (e.g. Hondius, Sanson, and Speede to name just a few). The concept proved highly resilient and continued to figure in maps for decades after Father Kino – who had traveled to northern California and witnessed its landlocked nature himself – published his observations in Paris in 1705. When Danckerts compiled and published his map in 1680, this was nevertheless still the norm and demonstrates that Danckerts and his family firm relied on convention on this particular point.

The Eastern Hemisphere also includes exciting new cartographic features to study. Australia, for example, is only partly represented, but despite the largely unknown southern and eastern coasts, the map nonetheless includes Abel Tasman’s recent discoveries of Tasmania and parts of New Zealand on both the eastern and western hemisphere maps. Korea is correctly represented as a peninsula, and even the Japanese archipelago is visible on the perimeter of the Eastern Hemisphere.

In the spaces above and below the intersection of the hemispheres, we find two smaller polar projections, which clearly show the discrepancy in cartographic knowledge between these regions. While the Arctic Circle is relatively well-rendered along the northern coats of Europe and Asia – including Greenland, Spitsbergen, and Nova Zemlaya – the Antarctic Circle is still a completely blank region on the map. The only feature visible in this inset is the southern tip of South America. The rest is void. Interestingly, correcting this error was one of the main drivers for producing a second state of this map (1685), in which the south polar projection was redrawn entirely.

As was customary in fine Dutch maps of the era, the four projections are surrounded by artistic allegorical scenes. Among the many representations, we find mythological scenes of gods, battle scenes, maritime scenes, and harvest scenes – all interspersed with a wealth of real and imagined beasts and monsters. More specifically, we may identify the four corner scenes as symbolic representations of the elements (clockwise from the upper left corner): FIRE as war and destruction; AIR as the heavens; WATER by the maritime sphere; and EARTH as husbandry and harvest (Shirley 1993: 461). Like the four map projections, these four scenes have all been more or less directly copied from the world map of Frederick de Wit’s Atlas Maritima from 1668 (for more on this, see the context section below).

A remarkable list of owners hand-written on the verso

Before moving on to the context in which Danckerts produced this map, it is important to briefly discuss some of the many hand-written annotations found both on the map itself and especially on the verso. Several place names and labels have been underlined throughout the two hemispheres using gold ink. The same hand has written the following into the void of the Atlantic Ocean, just northeast of Brazil: “seú Oceanus Atlanticús.” A seemingly second hand has used what appears to be a red pencil to underline further toponyms, including many in the Eastern Hemisphere.

It is hard to say who could be behind these annotations, but a good place to start would be among the impressive list of owners that have made notes on the verso. Turning the sheet over, we are confronted by an extensive schema of writing in four different hands along the right side of the sheet’s blank verso. These annotations appear to be an extended list of German owners, one of which has quite a bit to say on matters of geography and mapmaking.

Beginning in 1695 – only fifteen years after the map was first issued – the list spans a period of almost two hundred years. The oldest annotation is found in the lower right corner, although the trimming of the sheet has caused a small part of this annotation to be lost. However, what can be quite easily deciphered is that it was written in Latin by a friar named Ludovico, working from Frankfurt. It is dated 1695 and surrounded by a swirling pattern. Chronologically, the subsequent annotation is the largest of them all, comprising an impressive forty lines of text extolling the virtues of geography and some of its proponents. Here too, we are provided with a date (1754). The last two annotations are from the 19th century: the earlier one, Friedrich Schmidt, has had the last digit of the dating cut away, but the most recent owner, Ernst Gerhardt, dates his inscription to 1888.

A full transcription of the verso annotations is as follows:

Die Erlernen der Geographie ist höchst nützlich u. Höchstnötig. Kein zukünftiger Gelehrter kann selbige entbehren. Ich lasse alle Anleitungen dazu, daran man reiner, Mengel, deren vieler man Überfluss hat, ihren und schätze vornehmlich des berümten Herrn Johann Hübners u. Herrn Johann Jacob Schatzers Arbeit sehr hoch. Allein ich grüsse doch beiden und allen übrigen, H.M. Joh. George Hagers Stadt. Zu Chemnitz ausführliche Geographie, so in zen Teilen zu erst 1746 und zum anderen Male 1751 herausgekommen war. Denn er hat:

- durchgängig die Geliebten humanistischen zum Grunde gelegt,

- Das alzukurze, zu ausschweifende, zu trockene u. verworrene, welches man nach einigen (…) sorgfältig, vermieden und aus andern Wissenschaften allerhand angenehme, nützliche u. Notwendige Karte wider. (…) der obiges geborgen als z.B.

- a) aus de Naturelle, was in aus (…) der Luft, des Wassers und der Erde zu merken nötig ist.

- b) aus der Sittenlehre, was die Verschlossenheit der Einwohner in (…) ihres Natureles, Temperaments u. Hauptneigungen betrifft.

- c) aus der Politick, was die Geste. U. Weltlichen (…) angehet.

- d) aus den Geschichtsbüchern wo traurige Erdheben sich ereignet und was sich sonst am einem Orte Merkwürdiges zugetragen hat.

Wo man dieses alles zusammennimmt, so wird man mir sonder Zweifel zugestehen, dass sein Vortrag all zu kurz, zu ausschweifend, zu trostlos oder su verworren sei.

Richard Christian Kuster

des heil. Predigtamtes Candidat

Anno 1754

Friedrich Schmidt in Oderstadt 185…

Ernst Gerhardt. in Drohndorf. 1888

Hasce Tabulas Geographicas justo

Titulo Francofurti ad Oderam

Christ: Ludovicus Fried….

ao: 1695

Context is everything

This map shows the world as it was understood in the 17th century. While most of us are perhaps more familiar with the explorers of the 16th century (Columbus, Cabot, Magellan, da Gama, etc.), it was in many ways during the 17th century that we find the greatest age of exploration. Across the globe, brave mariners ventured fearlessly into the unknown, often paying for it with their lives, and every year a plethora of new reports, charts, and surveys would expand the data sets upon which cartographers could draw. The 17th century was, in other words, one of the most dynamic eras in cartography — an age in which the world itself was conquered through measurement and projection.

This particular chart is of some importance, both due to its age, rarity, quality, and decoration, but also because it writes itself into the history of cartography – and thus of geographic understanding – in a very particular way. Danckerts is known to have produced no less than two famous world maps in 1680, of which ours is one. In both cases, Danckerts copied more or less directly from an earlier world map by an even more famous mapmaker, namely Frederick de Wit.

The hemispherical chart of the world (1668) published in De Wit’s Atlas Maritima (1670) was then, as today, considered a masterpiece of Dutch cartography. But De Wit’s maps were monumental and expensive, meant for those who could afford to pay. Danckerts saw an opportunity to provide an equally impressive chart at a lower cost and to a broader audience. Among the mechanisms he applied to achieve this was the reduction of De Wit’s four-sheet chart into a single folio double, as seen here. Another means was having the plates drawn and engraved from scratch, based on a print of De Wit’s map. While Danckerts’ chart remains a crucial milestone of Dutch cartography, it is clear that a somewhat less skilled engraver has rendered the imagery of his map than in De Wit’s case. However, this judgment should be understood in light of the fact that De Wit employed the important Dutch master, Romeyn de Hooghe, as his primary engraver. Attaining his level of artistry was not only a question of resources. In De Wit’s case, it was an engraver with the vision and aesthetic of a great artist. That was indeed hard to copy. Other Dutch mapmakers also tried to emulate De Wit’s chart for commercial purposes, among them Gerrit van Schagen (1682) and Joachim Bormeester (1685), but none of them did it as successfully as Danckerts.

Five years after our map was published, Danckerts issued a second state of this particular map, in which he had redrawn the hemispheres and given the map a new title.

Cartographer(s):

Justus Danckerts (1635-1701) was a Dutch mapmaker born into a family of cartographers. He did most of his work under the aegis of his family’s publishing house in Amsterdam. His active career began around 1670 and ran for the duration of his life. Many of his maps were published in undated atlases, creating confusion in both chronology and attribution between his father Cornelis’s publications. In addition to his father, the firm employed his brother and at least two of Justus Danckerts’ three sons.

Condition Description

Margins extended, minor loss and wear.

References

Shirley no. 495 (p.503, 528)

The OCLC lists 25 occurrences of this chart, which is found in institutional collections worldwide, including the German National Libraries in Leipzig and Frankfurt, the Bayerishche Staatsbibliothek in Munich, The British Library, The Royal Danish Library, and the Biblioteca Nacional de España. One copy of the first state of this map held in the British Library constitutes a proof prior to the first state plate being finalized, as the rigging off the ships and other smaller features are missing. No other examples like this are known.