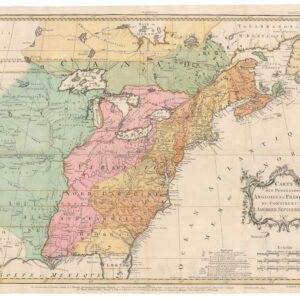

De l’Isle’s paradigm-setting chart of the Gulf of Mexico, the first accurate plotting of the full course of the Mississippi River.

Carte Du Mexique et de la Floride des Terres Angloises et des Isles Antilles du Cours et des Environs de la Riviere Mississipi

$1,800

1 in stock

Description

Unique access to the reports of French explorers and Jesuit missionaries allowed Guillaume de l’Isle to compile more accurate and detailed maps of North America than those of his contemporaries. Nowhere is this better exemplified than in the present chart of Mexico and Florida, which constituted a landmark in the French mapping of North America.

Produced in the earliest years of the 18th century, it became one of those maps that not only propelled its maker to fame and fortune but which prompted a comprehensive revision in the cartography of the West. When Guillaume de L’Isle became the royal cartographer for King Louis XIV in 1718, he had already been in the mapmaking business for decades. He joined the French Academy of Sciences in 1702 and would begin to produce maps of such extraordinary quality during the following years, eventually leading to his appointment to the French court. As such, De l’Isle became inheritor to the country’s cartographic reigns – a role that had been difficult to fill since the death of Nicolas Sanson some fifty years earlier.

De l’Isle produced this map during this formative period of his career and more than a decade before his elevation to royal circles. It nevertheless became so immensely popular that it was reprinted in no less than five different states and continuously issued up to 1783. Our example is the rare third state, issued in 1708. The respective states are relatively easy to identify because each contains distinct elements not included in the other states. The third state is identifiable by the Quai de Horloge address for De l’Isle’s workshop and the inclusion of the engraver’s name (Simoneau) below the title cartouche. State 1 includes De L’Isle’s first address on Rue Des Canettes; State 2 features the later Quai de Horloge address, along with the imprint of Louis Renard; State 4 bears the name Philippe Buache and the date 1745; and State 5, issued after the Declaration of Independence and the establishment of the United States includes a new title, and is dated 1783.

This particular map became so seminally important because of its originality and the sources that De l’Isle used to compile it. In addition to being a fascinating view of continental America during Europe’s colonial endeavors, it was the most up-to-date rendition of Nouvelle France available, particularly regarding the Great Lakes. It also significantly improved the depiction of English settlements along the East Coast. But De l’Isle’s most significant contribution to understanding North America’s geography was nevertheless his inclusion of new and essential data on the Mid- and Southwest.

The highlight in this regard was his accurate plotting of the full course of the Mississippi River, a cartographic feat not seen on a printed map before. But we are also provided with new insights into the distribution of Indian tribes and the mapping of early trials in the Southwest. In East Texas, New Mexico, and the Rio Grande Valley, the map plots local Indian villages in hitherto unseen detail.

De l’Isle’s ability to draw this refreshing view of the continent was based on his access to unique and vital sources. Some of the most important in that regard were the reports of Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and his younger brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville. Both had been born in Montreal as sons of a French administrator. While Bienville became the administrator of Nouvelle France and later Governor of Louisiana, the elder brother, d’Iberville, explored the south and established the French Territory of Louisiana in the first place. Both men maintained close contacts with the Spanish Missions that were gradually being established throughout the southwest as a means of cementing Spanish control of the region.

In addition to the records and reports from the highly active brothers, De l’Isle also had access to the foundational reports from Sieur de La Salle’s famous explorations of the Great Lakes, the Mississippi River valley, and the Gulf of Mexico and Mississippi Delta. Even though La Salle’s final expedition to the Gulf was marked by tragedy and misfortune (including the murder of La Salle himself at the hands of one of his own men), the survivors of his expeditions managed to get many of the important records back to France. Other sources for the compilation of this map came from French Jesuit missionaries, who interacted with their Spanish counterparts along the frontier and illegally copied their records for the French King.

The result of De l’Isle’s access to these incredible contemporaneous sources meant that he could produce a whole series of American maps, which revolutionized Europe’s geographical understanding of this still largely unexplored continent. The first to be issued was a large overview map entitled L’Amerique Septentrionale, published in 1700. Over the subsequent years, the larger overview was followed up by more focused regional maps, including our chart of Mexico and Florida, a new map of Canada and the Great Lakes (Carte du Canada ou de la Nouvelle France) in 1703; and a completely new map of the Mississippi Valley and Gulf coast in 1708 (Carte de la Louisiane et du Cours du Mississipi).

Ultimately, this is one of the most important and influential maps of the American Southwest to be issued in the early 18th century. Even today, experts consider the map a milestone in European cartography, with Professor William Patterson Cumming characterizing it as “profoundly influential” and California cartographic historian Carl Irving Wheat calling it a “towering landmark along the path of Western cartographic development.”

Context is Everything

The third state of De l’Isle’s iconic map appeared in 1708, during the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). This was a period of intense conflict and strife between the colonial overlords that now dominated North America. While the war erupted over who would inherit the Spanish throne, it was just as much a proxy war over control of the continent. The French Navy repeatedly tried to dislodge British control of the East Coast, attempting, among other things, to seize the critical port of Charleston in 1706 but failing. Further attempts to capture British-controlled areas were more successful but were usually followed by losses elsewhere. Neither party had the resources to oust the other.

When a peace treaty was finally signed in the Dutch city of Utrecht in 1713, recent French losses in Europe forced Louis XIV to cede most of the annexed territories back to the British (including the sugar-producing island of St. Christopher and peninsular Nova Scotia). The loss of these territories to the British soon prompted France to double its efforts to control the Americas. In 1718, New Orleans was founded as the new administrative capital of the enormous French Territory of Louisiana, and two years later, a new garrison and fort were established on the eastern tip of Nova Scotia – an unmistakable rebuke of the Treaty of Utrecht. In planning these strategic responses to the Utrecht peace, the French would have relied heavily on the details and exactitude of de l’Isle’s innovative cartography.

States of the Map

The states of the map can be identified as follows:

- 1703 – De L’Isle’s first address on Rue Des Canette

- 1703 circa – Address changed to Quai de l’Horologe a la Couronned de Diamans. A Renard/Amsterdam address is added as a second map seller

- 1708 circa – Address shortened to Quai de l’Horologe and Renard’s imprint removed.

- 1745 – Ph. Buache imprinted added in the bottom margin

- 1783 – Title changed to Carte du Mexique et des Etats Unis . . .

Cartographer(s):

Guillaume de l’Isle (1675-1726) was a French cartographer who was a key figure in the transition toward a more scientifically grounded cartography.

He was renowned for the extraordinary quality and accuracy of his maps. Especially his depictions of North America stand as some of the most critical milestones in mapping the continent, as they were based on the most up-to-date information available and had been culled of all mythical or imagined augmentations. De L’Isle also recalculated latitude and longitude based on the most recent celestial observations and incorporated these revisions onto his maps. In doing so, he set new entirely standards for cartographic accuracy.

De l’Isle came from a family of French cartographers, though none were as acclaimed as he would become. He trained under his father from an early age and later studied mathematics and astronomy under Cassini. This combination of practical mapmaking experience and a deep scientific understanding of cartographic principles allowed De l’Isle to become one of the most significant figures in early 18th-century cartography.

De l’Isle established his firm in his twenties, issuing his first atlas in 1700. Two years later, he became a member of the Royal Academy and moved his firm to the Quai de Horloge, a center for printing and mapmaking in Paris. In the following years, Guillaume De L’Isle would produce some of his repertoire’s most iconic and essential maps. In 1718, he was appointed Royal Geographer to King Louis XIV, a position which he maintained under Louis XV until his premature death in 1726.

Condition Description

Clean and bright with nice old color. Faint discoloration along centerfold, not affecting quality of the image.

References