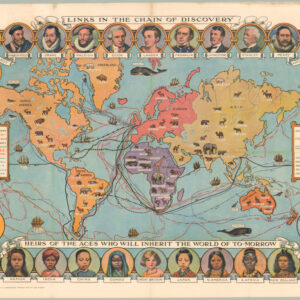

A set of four allegorical mezzotints referencing the great continents of the world.

[Set of Four Allegorical Mezzotints of the Continents] America. Europa. Africa. Asia.

$3,400

1 in stock

Description

This wonderful set of four hunting scenes, executed by Johann Elias Ridinger in the exuberant style of the Rococo, constitutes one of the most exquisite allegorical representations of the world as it was known in the 18th century.

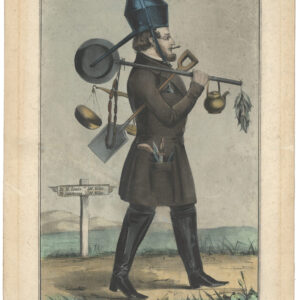

Executed as mezzotints, the scenes are kept in a flourishing Rococo style and represent the continents of America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. A mezzotint is a graphic created by endowing the printing plate with its own topography through an indentation process using a rocker. Depressions in the plate produce darker tones of ink, whereas smoothing and polishing the plate causes it to carry less ink and consequently print a lighter shade.

The artist behind these vivacious tableaus was German printmaker Johann Elias Ridinger, who, along with George Stubbs, was the greatest compiler of hunting and riding scenes in the 18th century. His compositions were cherished in European aristocratic circles, and Ridinger often used his scenes as vehicles for symbolism or allegory.

Hunting and riding scenes were ideal motifs for allegorical rendition, as the juxtaposition of nature versus culture was often blatant and the symbolism hard to overlook or misinterpret.

In essence, Ridinger’s four scenes constitute a commentary on the state of the world and the presence and role of European civilization. The hunter represents the masculine values of order and civilization. These traits are manifested in Europe’s growing global domination. On the other hand, nature represents chaos, the feminine, and the allure of the unknown and untamed.

Ridinger vividly represents this dichotomy by casting one of the continents in a wholly different light than the others. Unlike the foreign spheres of Asia, America, and Africa, the hunting scene on the Europe plate consists of an ordered process with an inevitable outcome. We see the type of parforce hunting in which European regents of the 18th century loved to engage. Within the framework of a controlled landscape, a great stag was released and chased by riders and dogs until exhaustion caused it to halt. Panting and paralyzed with fear and desperation, the animal was approached by the hunt’s leader (usually the aristocrat or prince), who then had the honor of killing the animal up close. Originally the death blow was done with a long knife or short sword, known as a Hirschfänger. But in Ridinger’s scene, this iconic blade has been replaced by a rifle, making the whole ordeal appear even most structured and secure and thus “civilized.”

The remaining three scenes stand in stark contrast to this romantic dream of a Europe in which nature has been relegated to the role of aristocratic entertainment. On the other plates, violent confrontations between man and beast – in some cases seemingly with deadly outcomes for the hunters – suggest that nature has yet to be tamed. The fact that these distant continents also sport incredible and ferocious beasts added to the natural drama of the situation.

The American scene is undoubtedly the most frightening and impressive of the three wild continents due to the presence of an enormous elephant or mastodon in the middle of the composition. While America has had no species of living elephants in over 12,000 years, Ridinger’s choice was probably inspired by one of the first paleontological discoveries in history.

In 1739, a mastodon’s partial skeleton was found in Kentucky, and the bones were subsequently shipped to Paris for scientific inspection. Their study reverberated throughout natural history circles in all of Europe, fascinating and intriguing both scientists and laypeople alike. Elephants had been known to Europeans since the time of Alexander the Great, but the notion that they once inhabited the Americas was a completely new idea when Ridinger published his scenes. It seems that the artist was well aware that his scene would cause a stir, for he provided it with one of the most dramatic captions to be found on an 18th-century print. It is offered both in German and Latin, with the latter reading:

Barbarus et barrus coeunt certamine diro,

Natura ac armis saevus uterque furit,

Est Elephas vastus, quem nutrit America dives,

Hostes conculcat planta, manusque premit.

The barbarian and the elephant meet in a dire contest,

Both savage and furious, one by nature, the other by arms,

The elephant is enormous, as America nourishes him with her richness,

He tramples enemies under foot, and crushes them with his hand.

In the two remaining images, we find similar ferocious scenes of local hunters engaging violently with their prey, showing Asia and Africa, respectively. In the Africa scene, two enraged lions throw a turbaned rider from his steed. The male lion is tearing at the horse’s bough, while a spearman and two bowmen are desperately trying to protect their master. Interestingly, it appears from the fallen Moor that he is carrying a cub swathed in linens, perhaps stolen from the very den of lions now attacking him. A similar dynamic seems to fill the Asia scene, where several turbaned riders chase wild animals. It is, however, only the man in the front of the scene who is actually under attack. In this case, the attacking predator is a leopard, but as in the Africa scene, it also seems that the animal’s young is somehow involved, as a cub lies frightened and submissive on its back in the forefront of the scene.

Ridinger’s works stand as some of the most symbolically loaded art of the era. With exquisite beauty and charging dynamism, he lifted the aristocratic themes of hunting and sportsmanship into a world loaded with mythological symbolism, metaphor, and allegory. Where many of his contemporaries produced the kind of sycophantic scenes that an inbred and introvert aristocracy craved, Ridinger endowed his hunting scenes with some of the great questions and challenges that confronted humanity in the late 18th century.

Cartographer(s):

Johann Elias Ridinger (1698-1769) was a German painter, engraver, draughtsman, printer, and publisher. He is considered among the best German printmakers of his day and is recognized as one of the world’s leading 18th-century artists when it came to the popular aristocratic themes of dogs, horses, and hunting.

Ridinger trained in Ulm with the painter Christoph Resch, but would later move to Augsburg to study under the eminent Johann Falch. Here he also learned the art of engraving from master Georg Phillip Rugendas. During a three-year stint in Regensburg, Ridinger would visit the royal stables almost daily, gradually mastering the horse as a motif. Around 1750, Ridinger established his own printing business in Augsburg, but only a few years later he was drawn away from his artistic output when offered the directorship of Augsburg Statsakademie in 1759.

Condition Description

Rich impressions. Trimmed to the platemarks, or just inside, in some places with loss of imprint. Some minor abrasions; see images.

References

![Flag Map of California [Signed in pencil by W.J. Goodacre]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/NL-01134_thumbnail-scaled-300x300.jpg)

![Flag Map of California [Signed in pencil by W.J. Goodacre]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/NL-01134_thumbnail-scaled.jpg)