Colossal 1909 map of the Ottoman Empire composed during the ‘New Great Game’and the lead-up to World War I

Nouvelle Carte Générale des Provinces Asiatiques de l’Empire Ottoman (sans l’Arabie) dressée par Henri Kiepert, Berlin 1883. Chemins De Fer d’après l’état de 1909.

Out of stock

Description

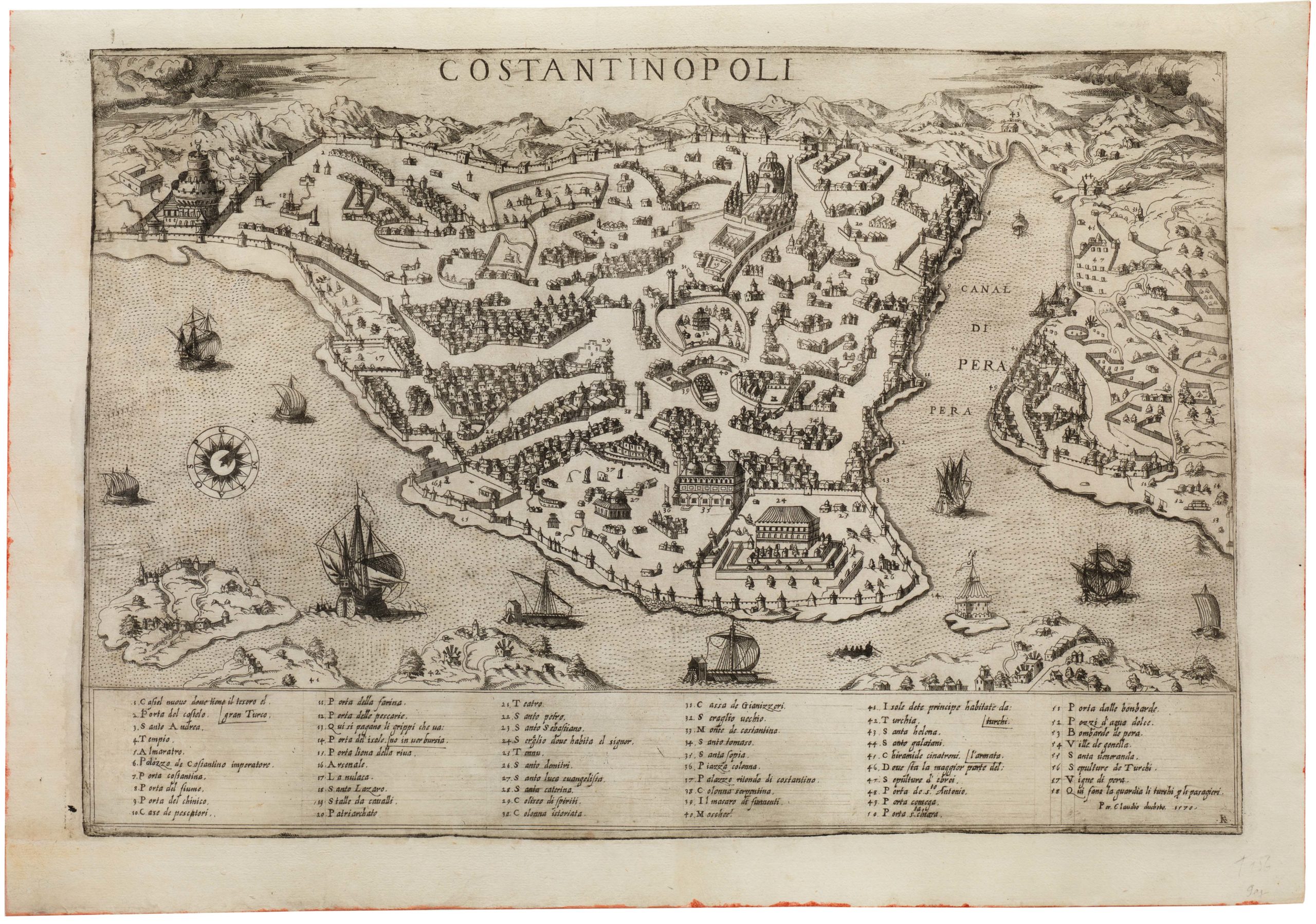

This impressive, large map depicts the heart of the Ottoman Empire, including Turkey, the Levant (modern Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan) and Iraq; plus adjacent regions, including parts of Persia (Iran), Egypt and the Caucuses. One of the most detailed and accurate geographical overviews of the region ever made to date, it was complied in 1883 by the immensely knowledgeable and well connected German geographer Heinrich Kiepert, and updated to 1909 under the supervision of Kiepert’s son, Richard, also a professional geographer. The present edition of the Kiepert map is especially interesting and important, as it, perhaps better than any other map, showcases the ‘New Great Game’, the grand German-Ottoman designs in the region, conducted at the expense of the new Anglo-Russian alliance, in the immediate run-up to World War I.

The Ottoman lands are outlined in pink, and show how the empire is virtually surrounded by enemy powers. In Europe, to the northwest, are Christian nations, former Ottoman possessions that had a ‘complex’ relationship with Istanbul, to say the least. To the northeast, are the Caucuses, outlined in green, which are possession of Russia, an ancient foe of the Ottomans. To the east, is Persia, outlined in yellow, the Turks’ oldest adversary. Event though Egypt is shown to normally be a part of the Ottoman Empire, in reality, it was controlled by Britain, a power that was increasingly at odds with Turkey.

The main map is exceedingly detailed, based on the most advanced scientific surveys available. The names of many geographical features and towns are given in a variety of languages, as explained in the table below the title. All major topographical features are depicted, with mountains expressed through shading. Innumerable cities and towns are noted in their precise locations, while all major roads and railways (many of which had been completed only recently) are delineated. Importantly, Kiepert includes ethnographic information, labeling the local peoples in each area, critical information in such a politically volatile region.

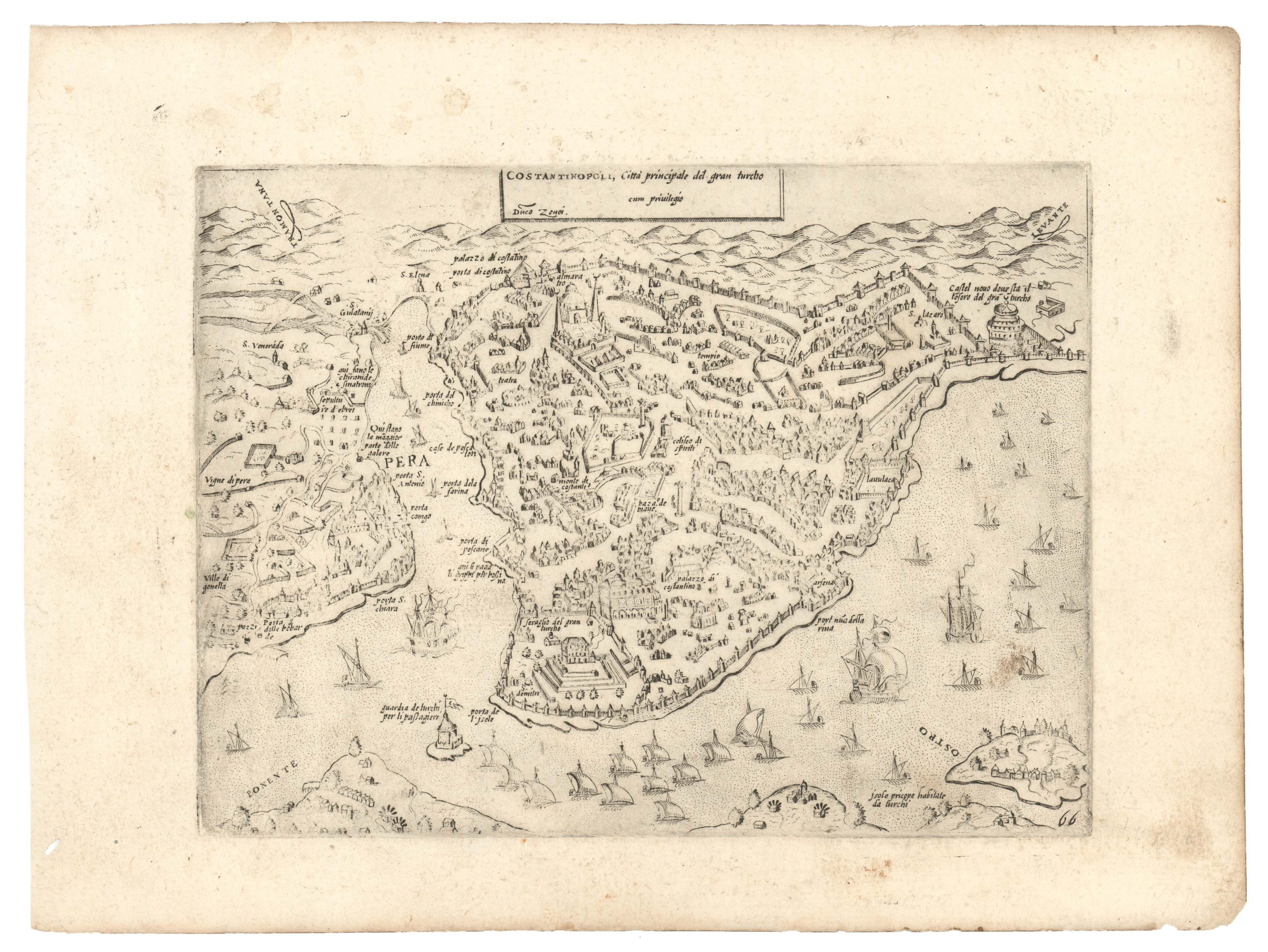

The separate, but accompanying smaller map, Aperçu General de la Division Administrative des Provinces Asiatiques de l’Empire Ottoman, is a political map of the area depicted on the main map. The map delineates the various sanjaks (vice-regencies), vilayets (provinces), and kazas (cantons), which are listed in the surrounding tables. Kiepert sensibly notes on the main map (in the lower-left corner) that he did not include these political divisions on the larger map, as it would leave it cluttered.

Heinrich Kiepert drafted the main map in 1883, and the first edition was chromolithographed onto 6 large sheets and published in 1884 by Dietrich Reimer in Berlin. The map was very highly regarded and examples were ordered by German industrial concerns and government agencies all across Europe. It was reissued in several updated editions, in 1891, 1898, 1899, 1909 (the present edition), 1910, 1912 and 1917. Richard Kiepert, Heinrich’s son, oversaw the editions issued after the elder Kiepert’s death in 1899.

The present example of the map bears the seller’s pastedown stamp of ‘Edward Stanford Ltd.’ of London, then the world’s leading publisher and dealer of cartographic materials. It also bears the former owner’s pastedown stamp of the Library of the Institute of Civil Engineers of Great Britain, in London, which suggests that some important individuals who were members of that august society likely consulted the map.

The ‘New’ Great Game: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and German-Ottoman Designs

It is not surprising that the present work, perhaps the period’s best general map of the heart of the Ottoman Empire, was made in Germany. By the beginning of the 20th Century, an increasingly ambitious and wealthy German Empire was looking for ways to gain its place under sun, preferably at the expense of Great Britain. While it knew that it could not likely acquire any major conquests in Asia comparable to the British colonies or the Russian holdings, it saw an opening to assume great political and economic power in the Middle East by stealth. The Ottoman Empire was decaying, lacking the financial and military resources to maintain its immense domain. The Germans seemed provide the perfect solution, as they offered to invest vast capital in the Ottoman lands, while promising not to assume political control over any of the territory – they only requested a business stake in their proposed mutual projects.

As presented on the map, there were two main German geo-strategic plays in the Ottoman Empire, both of which centred around the construction of railways. The first was to create fixed link from Istanbul to the Persian Gulf. Not only was the Gulf long considered a key British zone, but geologists were convinced that the region possessed immense reserves of oil, an assumption which would be proven true by 1908, the year before the present map was issued.

In 1903, the Germans, who had already sponsored the construction of the railway which ran from Istanbul to Aleppo (Syria), spearhead the construction of the Baghdad Railway (German: Bagdadbahn), which when completed would provide a direct link from Berlin to Basra, the gateway to the Persian Gulf (and presumably beyond that by sea to India). Both the Germans and the Ottomans would then be able to move large numbers of troops thousands of kilometres to the heart of the Middle East in only a few days – much faster than the British or the Russians. They could also have transported commercial goods from Asia to Europe far more quickly than through the Suez Canal. The famous contemporary orientalist Morris Jastrow observed: “It was felt in England that if, as Napoleon is said to have remarked, Antwerp in the hands of a great continental power was a pistol levelled at the English coast, Baghdad and the Persian Gulf in the hands of Germany (or any other strong power) would be a 42-centimetre gun pointed at India.” The uncompleted proposed main leg of the line, from Aleppo to Basra (and beyond) is shown as a dotted red line on the map, and this clearly shows both the uniquely great promise and threat of such a railway.

The other strategic play was for the Germans to control a railway extending deep down into the Red Sea area. The realization of such a line would threaten Britain’s naval dominance over the sea, and its vital link to India and Southeast and East Asia via the Suez Canal. The Ottomans had long dreamed of having a rail link from Istanbul to Medina and Mecca, so as to better facilitate the Hajj, and it seems that this religious imperative perfectly coincided with practical German ambitions. As shown on the map, the line of the Hejaz Railway had been completed from Damascus to Medina by 1908, with the dotted lines showing its intended extension to Mecca.

Meanwhile, Russia and Britain, whose rivalry had overshadowed the Middle East and central Asia since the 1830s, had both become exhausted, and tired of opposing each other in particular. Britain had won the Second Boer War (1899-1902) in South Africa, but at an awesome cost. Russia’s navy was crushed in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5), and the Czarist regime subsequently faced severe internal unrest. Moreover, both powers were more than a little spooked by the speed and success of the German operations in the Ottoman Empire. The dramatic expansion of the German military and a series of provocations had convinced both St. Petersburg and London that Berlin’s aims in the Middle East were far from peaceful. They saw Germany as being a far greater threat to their mutual fortunes than they were to each other.

Accordingly, both empires signed the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907, whereby Russia agreed to respect Britain’s domination of Afghanistan; Britain agreed to recognize Russia’s conquests in Central Asia; both parties agreed not to make moves on Tibet; and they mutually agreed to divide Persia into respective zones of influence. As shown on the present map, Russia gained control of an exclusive zone of interest that embraced all of Northern Persia, while Britain assumed agency over south-eastern Persia as far west as Hormuz, while the area between the two zones was to be open to both British and Russian activities. Curiously, the Russians and the British did not even bother to consult the Persian government, as even though Tehran protested, it was too weak to interfere with the Anglo-Russian plans in any meaningful way.

The ‘New’ Great Game became the Anglo-Russian design to hinder and contain the German-Ottoman alliance, the geo-strategic realities of which are perhaps no better illustrated than on the present map.

As it happened, the ‘New’ Great Game was not to last long. The Ottoman-German designs quickly collapsed during World War I (1914-8), with the British seizing Iraq and T.E. Lawrence, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ disabling the Hejaz Railway. After the war, Germany was utterly vanquished and the Ottoman Empire disintegrated, largely to Britain’s gain, making her the undisputed master of the Persian Gulf and its oil reserves. Nevertheless, the present map brilliantly illustrates the keystone region of global geo-politics during a crucial juncture in history.

Cartographer(s):

Heinrich Kiepert (July 31, 1818 – April 21, 1899) was a distinguished German geographer and cartographer renowned for his detailed and accurate maps. Born in Berlin, Kiepert developed an early interest in classical studies and geography, studying at the University of Berlin under notable scholars such as Carl Ritter and Leopold von Ranke. His expertise in historical and regional geography and meticulous approach to cartography set him apart in the field. Kiepert’s early works included maps for historical atlases and travel guides, highly praised for their precision and clarity.

Throughout his career, Kiepert produced numerous influential maps and atlases, including his notable Atlas von Hellas und den hellenischen Kolonien (1846) and the Formae Orbis Antiqui (1893). These works were instrumental in studying ancient geography and were widely used in German educational institutions.

Condition Description

Good; some areas of light toning, separations in linen at some folds (since mended) with very minor chipping and loss to edges of few map sections; case heavily worn with loss to upper part of spine. Dissected into 65 sections and mounted upon original linen (104 x 172 cm / 41 x 67.5 inches), plus smaller chromolithographed political map, dissected into 10 sections and mounted upon original linen (33 x 55 cm / 13 x 21.5 inches), all folding into original card case, pastedown seller’s stamps of ‘Edward Stanford Ltd.’ and former pastedown owner’s stamp of the ‘Library of the Institute of Civil Engineers’ of Great Britain.

References

La Géographie: Bulletin de la Société de géographie, vol. 19 (Paris, 1909), p. 367; Cf. (Ref.: 1912 edition): G7420 1884 .K5.

![[Mısır Haritası / Map of Egypt]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/NL-02391_thumbnail-2-300x300.jpg)