Anonymous French manuscript map of Mombasa Island, likely created by an early French slaver sailing on Omani-controlled East Africa in the mid-18th century.

[Manuscript] Plan du Port de Mombase

Out of stock

Description

This remarkable French manuscript map depicts the Island of Mombasa – one of the most important ports of trade on the East African coast and a centuries-old locus of empire, slavery, and colonization. The map is undated but appears to have been sourced directly from the new nautical atlas, The English Pilot, whose third and decisive volume was published in 1734.

Several clues suggest that the map was produced in the early 1740s. Its features are much closer to the 1734 English Pilot chart than a chart of Mombasa drawn by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin, published in 1749. Furthermore, the paper used for the manuscript map has a watermark that experts date to the 1740s (https://www.memoryofpaper.eu/BernsteinPortal/appl_start.disp).

The map is anonymous, but the quality of its execution suggests that an experienced navigator drew it. Given the time frame, the most likely explanation is that it was created by a French slaver preparing to sail on the Omani-controlled port of Mombasa around 1740.

Of the European powers, only France and Portugal entertained serious mercantile ambitions in East Africa during the first half of the 18th century. British interest in this region was primarily a Victorian phenomenon, and the British colonization of Kenya did not begin in earnest until 1901.

After the expulsion of the Portuguese in 1698, French slavers were the only Europeans to consistently trade with the Omani Sultanate in Mombasa (Alpers 1970). Between 1735 and 1770, French trade – especially in slaves – boomed. Our map, which shows the island of Mombasa, including the surrounding headlands and the maritime approach, was likely drawn as a preparatory measure for a slaving expedition. With the third book of The English Pilot hitting the market a year before this trade took off, it makes sense that the cartographer behind the manuscript map adapted it from the most seminal nautical atlas of the age.

Background

After the Portuguese broke into the Indian Ocean, they quickly set about recasting the centuries-old trade systems in place there. The intention was to cement their new oceanic empire. The Portuguese had won the day by employing superior firepower and ship technology, but they would hold it by establishing an impressive string of fortresses and factories (trade stations) all around the Indian Ocean. Mombasa was among the first places that the Portuguese subjugated. Their presence there began with Vasco da Gama in the 15th century and continued until the Omani Sultanate took the city in 1698.

Mombasa Island is a three-by-two-mile coral outcrop located at the mouth of the Mombasa River on Kenya’s Indian Ocean coast. While Mombasa today has grown far beyond the scope of the coral island, remnants of the original Portuguese settlement (known as Old Town) can still be found along the island’s northern shore.

Features of the map

The map depicts two fortified settlements: one facing west or the mainland (labeled Mombase), and one facing the sea. The latter appears unlabelled, possibly a deliberate misrepresentation by the compiler, who we must remember was working after the Portuguese had lost Mombasa to the Omani Sultanate.

The original Portuguese settlement was dubbed Santo Antonio after Lisbon’s patron saint and was located on the northeast of the island. This port was guarded by the large fortress known as Fort Jesus, which the Portuguese erected in the 1590s. Since construction occurred during the short-lived Iberian Union (1580-1640), it was actually built on the order of Felipe II, King of Spain. Fort Jesus constitutes one of the most fascinating examples of Portuguese colonial architecture in Africa, in that it was built by a Milanese architect – Giovanni Battista Cairati – who designed it in the style of a Late Renaissance Tuscan fortress but then buttressed it like a Portuguese garrison. Yet despite this distinctly European design, all materials and labor used were indigenous, creating an exciting architectural amalgamation specific to this time and place.

Both forts appear to be flying the same flag. Although the nature of this flag is unidentifiable, it probably constitutes a simplified representation of the flag of the Omani Sultanate, which controlled the island between 1698 and 1856. Even under Islamic rule, we find several churches represented on the island, though interestingly, none of them appear to be named. This may be because they had gone out of function by then, but it could also be a deliberate omission to avoid confrontation with the Omani authorities.

The history of Mombasa’s mapping

Mombasa was an important port of trade long before the Portuguese entered the Indian Ocean in the late 15th century, and it continued in this capacity under Portuguese dominance. The Portuguese quickly realized the value of Mombasa, and even the first commanders, like Vasco da Gama, made significant efforts to integrate it into the new sphere of Portuguese control. Being expert seafarers and navigators, the Portuguese secured the commercial approach to the island by taking depth soundings and mapping out sand banks and shallows. While the resulting charts were guarded as state secrets in the 16th century, by the 17th century, this information was gradually becoming available to European mapmakers.

There are multiple 16th-century depictions of Mombasa, including a city view published in Braun and Hogenberg’s famous city atlas Civitates orbis terrarum from 1572. But these were largely schematic in their rendition. A more detailed map of the island, which included the first depth soundings, was produced by the Portuguese hydrographer João Teixeira Albernaz, who created his maps before the Omani Sultanate expelled the Portuguese from Mombasa in 1698. Among his enormous output, Teixeira produced an important map of the East African coastline with three detailed insets of African ports, one of them Mombasa. The inset included important navigational information such as depth soundings, which Teixeira had access to as hydrographer to the Spanish and Portuguese kings (Phillip III and João IV, respectively). When Teixeira’s map was published around 1672, it was nevertheless by the French polymath Melchisédec Thévenot. In this way, nautical information on East Africa passed from the Portuguese sphere of cartographic awareness to that of the French.

The earliest French map of Mombasa Island was by Pierre Mortier, which Jaillot published in a new edition of the Atlas Nouveau in 1708. As in Teixeira’s map, Mombasa figured as an inset on a larger map of the Red Sea and Zanzibar coast (Carte Particuliere de la Mer Rouge). Its inclusion reflected a growing French commercial interest in East Africa – especially for slaves (Alpers 1970; Vernet 2009). However, a dedicated map of the island was not published until Jacques-Nicolas Bellin’s map in L’ abbe Prévost’s Histoire Générale des Voyages (1749). Within the repertoire of French cartography, these two maps form chronological bookends to our remarkable chart.

Our manuscript map was compiled as a practical document that noted crucial nautical information such as shallows and depth soundings. Studying these, we note that the numbers on our chart differ from those on the Mortier/Jaillot map but match the numbers on Bellin’s map. The primary source for the Mortier map seems to be Thévenot’s publication of Teixeira, for everything – from soundings and placenames to the features included – is identical to Teixeira’s map. In comparison, our chart (and the Bellin map) contain a completely different dataset. Our map was clearly drawing on another, better source than Mortier.

Groundbreaking English cartography and a French trade boom

When the English hydrographer and mapmaker, John Thornton, joined the combine to complete John Seller’s English Pilot project in 1677, he not only brought experience and know-how to the table, but also an abundance of geographic data that he had accumulated as Royal Hydrographer. We know that both John Thornton and his son contributed a number of charts to the third volume of Page & Mount’s English Pilot, which was published in 1734. This contribution significantly elevated the project’s quality and was crucial to its popularity. Among the charts included was a map attributed to Samuel Thornton, John Thornton’s son and heir, entitled: “A New Draught of the Island of Madagascar at St. Lorenzo With Augustin Bay and the Island of Mombass at Large.” This map includes an inset of Mombasa that not only breaks with the Teixeira model but aligns perfectly with our manuscript map in the following manner:

- Thornton’s inset applies the same upside-down orientation as our manuscript map, in which south is at the top.

- The depiction of the geographical grid is found only on the island itself. Cutting through the latitudinal line is the toponym of the Portuguese settlement and church facing the sea: Nossa Senhora de Esperanca. While the toponym clearly denotes the settlement, it has been drawn onto the map in a manner that makes it seem like it is labeling the latitude rather than the settlement. Our manuscript mirrors this but takes it further, revealing an obvious progression from the Pilot map.

- The most important detail is the fact that all of the depth soundings on the Thornton chart match the readings on our manuscript map exactly, suggesting it was a template for the Bellin chart as well, although Bellin omits the two soundings at the opposite end of the island.

- In addition to the extra depth soundings, the island’s western end also includes a fortified settlement that is not on any of the French maps. This site is labeled Mombass both on our map and the Thornton chart.

The Thornton chart also has other elements that match conspicuously well with our manuscript map but imperfectly with any of the printed French maps. These elements include the labeling of the sand bank near the entrance to the island. On the Teixeira map, these are labeled Pouco fundo in Portuguese, roughly translating to ‘little depth.’ This terminology is maintained in the Mortier/Jaillot map but has disappeared from the Bellin. On the manuscript map, there is a single label off the northern shallow that reads’ pointe fonda,’ but other than this, the sandbanks are just drawn in. It is in the Thornton map that we discover the connection. Here, the original Portuguese terminology is still applied, though completely erroneously, suggesting that the compiler did not fully understand the meaning. Teixeira’s two labels, ‘ pouco fundo,’ have in Thornton’s chart been moved to the land promontory on the southern side and to deeper waters outside the sandbank on the north. The northern sandbank has, in turn, been labeled ‘should,’ which could refer to shoulder, but most likely is a contraction of shallow. Interestingly, this trend is repeated in our map, which only demarcates the shallows, but doesn’t label them, while the term ‘pointe fonda‘ is located in the open waters beyond the shallows.

Watermark and Dating

The paper is watermarked with “B★C★RICHARD,” corresponding to Bernstein 0019272A, 0019300A, and 0019307A. This paper was manufactured in Auvergne and its use is traced to between 1742 and 1749, thus providing a narrow range for the production of this map.

**Co-owned with BLR Maps in La Jolla.

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Manuscript chart in pen & ink with a light ochre wash depicting sand bars, on a clearly watermarked rather coase 18th century paper. Some offsetting & damp staining.

References

Edward Albers (1970). The French Slave Trade in East Africa (1721-1810). Cahiers d'études africaines 10,37: 80-124. (https://doi.org/10.3406/cea.1970.2845)

Monique de la Roncière (1965). Manuscript Charts by John Thornton, Hydrographer of the East India Company (1669-1701). Imago Mundi 19: 46–50. (http://www.jstor.org/stable/1150328)

Thomas Vernet (2009). Slave trade and slavery on the Swahili coast (1500-1750). In Slavery, Islam and Diaspora, pp.37-76.Edited by B.A. Mirzai, I.M. Montana et P. Lovejoy. Africa World Press.

![[With Extensive Contemporary Annotations] Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai Made in 1868-9 By Captains C.W. Wilson, and H.S. Palmer, R.E. Under The Direction of Major-General Sir Henry James, R.E. F.R.S. &c. Director of the Ordnance Survey](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/NL-00842_Thumbnail-300x300.jpg)

![[With Extensive Contemporary Annotations] Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai Made in 1868-9 By Captains C.W. Wilson, and H.S. Palmer, R.E. Under The Direction of Major-General Sir Henry James, R.E. F.R.S. &c. Director of the Ordnance Survey](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/NL-00842-scaled-300x300.jpg)

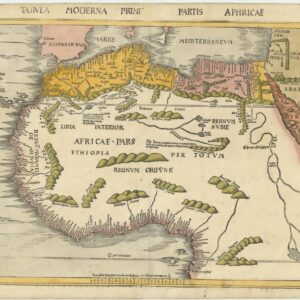

![[Title on Verso] Tabula Prima Aphricae Continent Mauritania Tingitanam, & Mauritaniam Caesariensem](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NL-00293_Thumbnail-300x300.jpg)

![[Title on Verso] Tabula Prima Aphricae Continent Mauritania Tingitanam, & Mauritaniam Caesariensem](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NL-00293_r-scaled-300x300.jpg)