Merian’s 1638 Bird’s Eye View of Hangzhou, China.

Xuntien alias Quinzay.

$575

1 in stock

Description

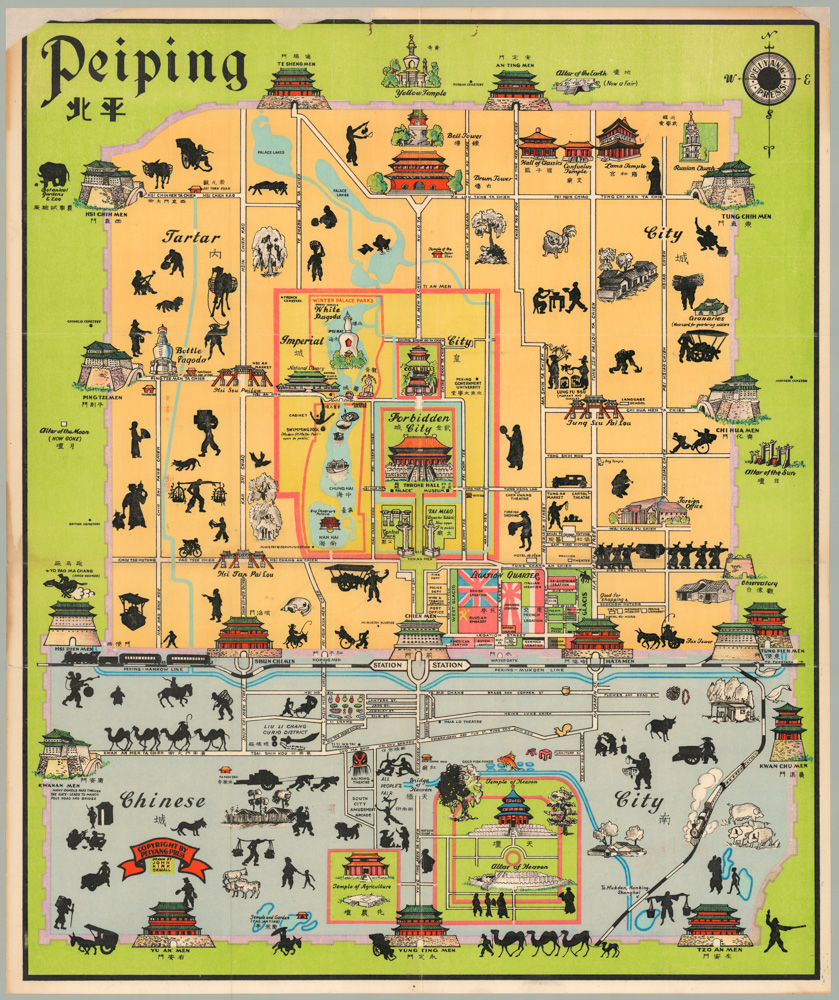

In the 1630s, European audiences had seen depictions of exotic cities like Tenochtitlan or Cusco, but Merian’s Quinzay was the first detailed view of a Chinese metropolis.

This is Matthäus Merian’s extraordinary bird’s eye view of the ancient Chinese city of Hangzhou (杭州市), the Ming emperors’ capital of the Zhejiang Province. Hangzhou was one of the major Chinese cities that Marco Polo described in great detail. It was a coastal trade hub that connected the markets of southern China with the rest of the world. This role is clearly reflected in Merian’s composition of the city, which is surrounded by a natural harbor and equipped with countless features to accommodate the maritime trade. Large ocean-going vessels are approaching the city via a narrow opening to the sea at the bottom of the image. This natural gateway to the city is protected by extensive fortifications, between which a thick chain prevented ships from entering or exiting the city without proper permissions.

Hangzhou was one of China’s eight historic capitals, serving as the principal city of the southern provinces during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Unlike Beijing, Hangzhou is an ancient city. It was founded over 2,200 years ago by the Qin Dynasty Emperors who united China and initiated the “Imperial Age” in Chinese history. Hangzhou was also one of the first South Chinese cities seen by a European when Marco Polo visited in the late 13th century. His description of the city shows that Polo was deeply impressed by its size and breathtaking beauty. Polo recounts how the city was built on a large lake, roughly 30 miles in diameter. At the lake’s center are islands with pavilions and palaces forming the city’s nucleus. Among the many features Polo tries to describe is the intricate network of paved roads and navigable canals within the city. The latter undoubtedly reminded him of home, although with more than 12,000 urban bridges, Hangzhou probably even outshone his native Venice (Polo is infamous for exaggerating, though).

The first European map of a Chinese capital

Like most European cartographers working on Asia in the 17th century, Merian was fascinated by Marco Polo’s accounts and incorporated many of the features described by Polo into his bird’s eye view. Merian was the first to seriously attempt a comprehensive and realistic view of a great Chinese city. Inspired by some of the great collators of the 16th century (e.g. Theodor de Bry or Braun & Hogenberg), Merian published this view in 1638 as part of his Archontologia Cosmica. It was the first cartographic city view dedicated to a Chinese city at the time.

By 1653, Jan Janssonius also published a map of Hangzhou in his city atlas, Theatrum Urbium Celebriorum (part VIII). The map was larger than Merian’s view and, in many ways, more embellished. Janssonius had acquired the original Braun & Hogenberg Civitates plates and used these as the foundation for his atlas. The view of Hangzhou did not originate from this source but was built on a combination of Merian’s view and Janssonius’ reading of Polo’s travelogue.

European Corruption of Hangzhou

A note should be made on the odd title that Merian gave his iconic view: Xuntien alias Quinzay. Until the 20th century, the city of Hangzhou was known as Quinzay among Europe’s intelligentsia. The term is essentially a linguistic corruption of the Chinese toponym King-sze, which roughly translates to “capital” or “Big City.” The term Quinzay can be traced back to the accounts of Marco Polo, who visited Hangzhou in the late thirteenth century and was spellbound by it. While Quinzay is a direct reference to Hangzhou, the preceding term – Xuntien – constitutes a similar corruption of the regional name Shuntian Prefecture (顺天府), of which Hangzhou was the capital.

Martino Martini and the Jesuit Connection

While Merian undoubtedly drew heavily on the Polo account, his compilation may also have been inspired by another European presence in the city, namely the Jesuit Order. The Jesuits were among the first Europeans to settle in the Far East. In 1549, the Spanish Jesuit Francis Xavier landed in western Japan. A few decades later, in the early 1580s, Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) arrived in the Guangdong province of China, settling first in Nanchang (1595), then in Nanjing, and by 1601, in Beijing. Initially, their presence was sporadic and careful, with Jesuits often dressing up as Buddhist monks to avoid confrontations. However, the torture and violence that Jesuit missionaries were experiencing in Japan was not replicated in China, and by the 1630s, the Jesuits had become a permanent fixture of the city. It is entirely possible that Merian used Jesuit reports alongside the Polo account to get some of the details in his view just right.

In 1648, Martino Martini became head of the Jesuits in Hangzhou. Martini dabbled in cartography alongside his missionary work, and soon, he led an initiative to construct a new church in Hangzhou. The complex was directly inspired by the Gesù Church in Rome, and Hangzhou soon became the Jesuit headquarters in China. Martini died in Hangzhou in 1661 and was interred in the city. Even though his tomb and church were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, they have since been rebuilt and are now part of the city’s cultural heritage.

Cartographer(s):

Matthäus Merian (September 1593 – 19 June 1650) was a Swiss-born engraver who worked in Frankfurt for most of his career, where he also ran a publishing house. He was a member of the patrician Basel Merian family.

Early in his life, he had created detailed town plans in his own unique style, for example plans of both Basel and Paris (1615). With Martin Zeiler (1589 – 1661), a German geographer, and later (circa 1640) with his own son, Matthäus Merian produced a collection of topographic maps. The 21-volume set was collectively known as the Topographia Germaniae and included numerous town-plans and views, as well as maps of most countries and a world map. The work was so popular that it was re-issued in many editions. He also took over and completed the later parts and editions of the Grand Voyages and Petits Voyages, originally started by Theodor de Bry in 1590. Merian’s work inspired the Swedish royal cartographer, Erik Dahlberg, to produce his Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, which became a cornerstone in European mapping.

After his death, his sons Matthäus Jr. and Caspar took over the publishing house. They continued publishing the Topographia Germaniae and the Theatrum Europaeum under the name ‘Merian Erben’ (i.e. Heirs of Merian). Today, the German travel magazine Merian is named after him.

Condition Description

Even mild toning.

References