One of the oldest maps of Persia and Mesopotamia, the Cradle of Civilizations.

[Persia & Mesopotamia] Tabula Quinta de Asia.

$16,500

1 in stock

Description

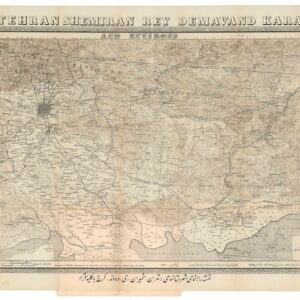

This is Francesco Berlinghieri’s Tabula Quinta de Asia, one of the rarest and most desirable early maps of Persia and Mesopotamia, where some of history’s first great civilizations arose, including some of the earliest agriculture, urbanism, and writing. It comes from Berlinghieri’s ground-breaking Ptolemaic atlas, Septe Giornate della Geographia, an innovative and exceptional volume first published in 1482.

In modern terms, most of the area shown on the map corresponds to the contemporary nation-states of Iraq and Iran (with parts of Kuwait, Azerbaijan, and Armenia also showing). This region has a richly varied topography, in which spheres of political and cultural influence are defined by natural boundaries formed by mountain ranges, rivers, or the sea.

The most notable feature on the map is the Zagros Mountains (Choathra Mote). Just as this massive range separates the modern nation-states of Iraq and Iran, it once separated the ancient Mesopotamian cultures from their Persian counterparts. In Berlinghieri’s map, the Zagros Mountains are shown linking up with the Taurus Mountains of southern Anatolia (Niphate Mote), in effect walling off Mesopotamia to the left side of the map.

Mesopotamia

The other notable feature on the map is its many sizable rivers. ‘Mesopotamia’ means ‘between the two rivers,’ referring to the floodplain between the great Euphrates (Eufrate Fl.) and Tigris (Tigri Fl.). The designation is not indigenous to the region but a later Greek name given to this area by geographers such as Strabo and Ptolemy. It was along this valley that some of the first civilizations developed.

Berlinghieri depicts the rivers of Mesopotamia with thick dark lines flowing south from the Taurus Mountains and into the Persian Gulf. Their actual course is somewhat different than what is represented here, but there is a degree of logic to the zig-zagging flows. Ever since the first civilizations developed here, manipulating river flow has been crucial for irrigation. This technology allowed agriculture to be harnessed to control food production. Generating surplus in food production was the essential pre-requisite that allowed humankind to develop all its other decisive attributes – from social hierarchies to empires.

Within Mesopotamia, we note the regional toponyms of Assyria in the north and Babylonia in the south. Among the significant centers noted in this region, we find most along the banks of the rivers. We see the great western capital of the Persian Sassanid dynasty at Ctesiphon on the Tigris River, and slightly further downstream – at the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris – is the ancient capital of Babylon (marked but not labeled), which in the 9th century CE was transformed by the Abbasids to become the Iraqi capital of Baghdad. Even though Baghdad lies on the banks of the Tigris, it is correct that its location is where the two river flows are closest to each other.

Ancient Iran

Moving east across the Zagros Mountains, Susa is one of the first famous place names to note. This was the capital of the Elamites, the greatest enemy to Mesopotamian kingdoms for millennia. Persian geography was generally not well-known to Europeans in Antiquity or during the Renaissance when this map was produced. A few key sources defined the region for both Ptolemy and Berlinghieri. While Ptolemy drew on ancient texts such as Xenophon’s Anabasis and the accounts of Alexander the Great, Berlinghieri also consulted the travels of Marco Polo.

The map’s geography of Persia is an excellent window into how this ancient region was understood in late 15th-century Europe. Territories are labeled according to ancient Persian dynasties, such as Media and Parthia. The Elbrus Mountains near the Caspian Sea have been moved inland, pushing the Central Iranian Plateau (Parthia) to the east. At the eastern edge of the map, Persia is delineated by another mountain range marked Masdorano Mo., which essentially denotes the Khorasan and Sistan Mountains and thus border with Afghanistan and Central Asia.

Berlinghieri’s map also includes two unusual illustrated place names:

- The Gates of the Zagros (Porta di Zagro), a label found in the easternmost reaches of the Zagros Mountains and enhanced with a simple vignette of a double gate. This represents the most critical pass across the mountains, known and fought over since the Bronze Age. It is one of the significant passes across the Zagros (i.e. the Tang-e Meyran).

- Slightly to the northwest of the gates and in the region labeled Media is a small depiction of a flower. Below it, we find the name Martiana Palube. Despite our best efforts, we have yet to determine the nature of this place name or the meaning of its rendition. It is one of many toponyms from 15th-century Ptolemaic atlases we can no longer identify.

Berlinghieri: A Unique Tradition of Cartography

The cartography of Francesco di Niccolo Berlinghieri is viewed as a distinct tradition within the framework of Ptolemaic mapmaking. Most scholars agree that Berlinghieri used sources different from his contemporaries to delineate the world’s land masses. The configuration of the Mediterranean, in particular, appears to have drawn on alternative sources. A common explanation is that Berlinghieri, as a Florentine, had access to far older and more accurate portolan charts and possibly even sources from within the Islamic world. Unfortunately, confirming what those alternative sources might have been remains speculative.

An important distinction between his Ptolemaic atlas and other 15th-century versions was Berlinghieri’s deliberate use of the archaic homeotheric or equidistant cylindrical projection, which is attributed to Ptolemy’s predecessor and primary source of geographic information: Marinus of Tyre (c.100 CE). As far as we know, Ptolemy never actually made maps himself, so we do not know which projection he favored.

Nevertheless, by the time the first Ptolemaic Geographies were going into print, most mapmakers had shifted to the new trapezoidal projection attributed to German cartographer Donnus Nicolaus (c.1420-1490).

Cartographic scholar Peter Meurer points out that all known Ptolemaic Geographies from the 15th century were built directly on the manuscripts of Donnus Nicolaus but that Nicolaus himself used different projections over time. While the new trapezoidal projection, known as the “Donis-projection,” was used in the Rome Ptolemy and the influential maps of Henricus Martellus, the Ulm edition returned to an equidistant cylindrical projection to present the new and updated understanding of Scandinavia based on the work of Danish cartographer Claudius Clavus.

Berlinghieri’s Septe Giornate is the only 15th-century atlas to use multiple projections depending on what parts of the world were presented. The creative process behind the Septe Giornate thus differed from that of contemporary Geographies.

States of the map

For a long time, most scholars agreed that much, if not all, of the Septe giornate was completed by 1479, including the maps, which were interpreted as having been printed in a single large batch and then subsequently bound and published in 1482 (Skelton 1966; Campbell 1987). A significant number of extra sheets were left over from the original printing. After Berlinghieri died in 1501, these were purchased and bound into a new edition with a new title page issued around 1503-1504.

A new and comprehensive study by Peerlings and Laurentius (2023) has nevertheless managed to identify subtle distinctions in many of Berlingheiri’s maps, denoting that there were amendments made and that different states thus exist.

For Tabula Quinta de Asia, Peerlings and Laurentius identify two distinct states (2023: 1884-185), which can be distinguished by over-printing one letter in a single regional toponym. Located on the left side of the map, near the centerfold and just above the central meridian, we find the regional toponym: SAGARTII or SAGAREII. SAGARTII indicates the first state, and SAGAREII (with the ‘E’ overprinted) marks the second state. The current example is the second state.

Census

There are several listings of Berlinghieri’s Septe Giornate in the OCLC, including at the Universities of Oxford, Manchester, and Yale, as well as with the New York Public Library, the LIBRIS library in Stockholm, and the Morgan Library and Museum in New York (no. 644313849). For the Tabula Quinta de Asia, the OCLC has only two listings, one at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich (no. 164796934) and one at Middlebury College in Vermont (no. 227145483).

Cartographer(s):

Francesco di Niccolo Berlinghieri (1440–1501) was a 15th-century Italian scholar, humanist, and a keen student of Classical Greek learning. He was one of the first Italians to print a text based on Ptolemy’s Geographia, which he supplemented with his other great passion: poetry.

Niccolò TedescoNiccolò Tedesco (a.k.a. Nicolaus Laurentii; Niccolò di Lorenzo) was a German printer who lived in Florence during the late 15th century. He most likely learned the basics of printing in his native Wroclaw. Tedesco was among the first Italian printers to use copper plate engravings, and he was behind a number of important works from the Italian Renaissance.

Having moved from what is today Poland to Florence, Tedesco first worked in a nunnery of the Dominican Order, where the sisters served as compositors and printers. Among Tedesco’s most famous works, we find Cristoforo Landino’s commentary to Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (first printed in 1472) and the Septe Giornate della Geographia di Francesco Berlinghieri, which was among the first printed atlases based on Ptolemy.

Condition Description

Very good. Minor wear and age.

References

Abshire, Corey, Dmitiri Gusev, Sergey Stafeyev & Mengjie Wang (2020). Enhanced Mathematical Method for Visualising Ptolemy’s Arabia. e-Perimetron 15, 1: 1-25.

Campbell, Tony (1987). The Earliest Printed Maps (1472-1500), British Library: London.

Gibson, D. (2013). Suggested Solutions for Issues Concerning the Location of Mecca in Ptolemy’s Geography.

Nabatea Hamad bin Seray (1997). The Arabian Gulf in Syriac Sources. In: New Arabian Studies, Vol. 4. G.R. Smith & B.R. Pridham (eds.). Exeter: Exeter University Press. Pp. 205-232.

Helas, Philine. (2002). The "Flying Map". Le 'Septe Giornate della Geographia,' by Francesco Berlinghieri \ dedicated to Federico da Montefeltro and Lorenzo de Medici, and depictions of the world in 15th-century Florence (Cartography). Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 46: 271-320.

Peerlings, R.H.J. & F. Laurentius (2023). Berlinghieri’s Geography Unveiled. Freely available at www.berlinghieri.eu Skelton, R.A. (1966). A bibliographical note prefixed to the facsimile of Berlinghieri’s Geographia, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum: Amsterdam.

Meurer, Peter H. (2007). 42 - Cartography in the German Lands, 1450–1650. In The History of Cartography, Volume 3, Part 2. David Woodward (ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 1182–1183.

![[Arabian Peninsula] Tabula Sexta de Asia.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/NL-02008-NEW_thumbnail-300x300.jpg)

![[Great Game] Map of Aderbeijan compiled principally from personal observations and surveys made in the years 1851-55 by N. Khanikof…](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NL-01994_thumbnail-300x300.jpg)