A true first state of one of the earliest maps of the Eastern Seaboard.

Tierra Nueva.

$1,800

1 in stock

Description

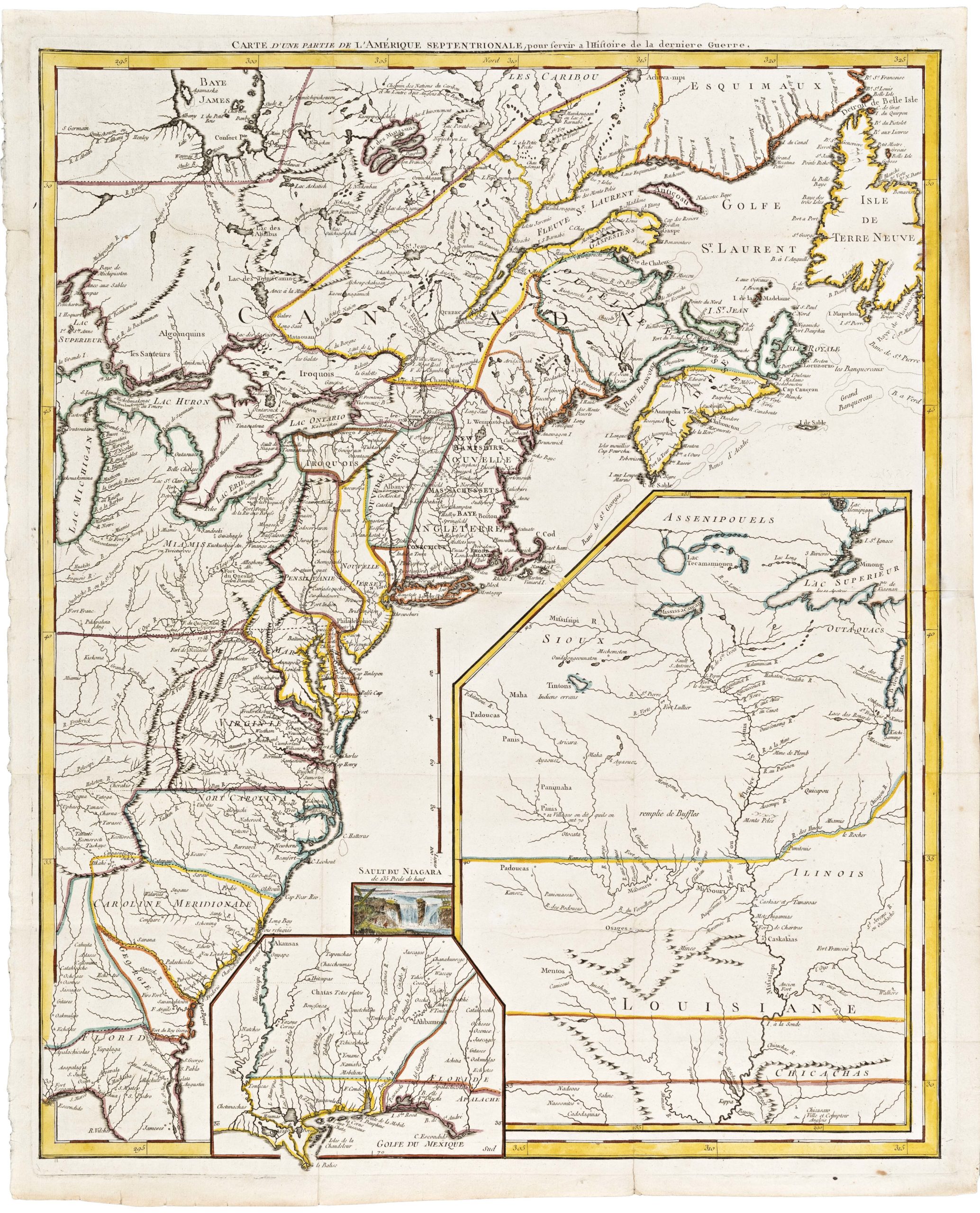

This is the first state of Girolamo Ruscelli’s 1561 map, Tierra Nueva, which represents a decisive moment in the cartographic history of North America’s Atlantic seaboard.

In this map, Ruscelli offers us an early and highly influential depiction of what eventually would become New England and the Maritimes of Canada. The map was compiled for Ruscelli’s edition of La Geografia di Claudio Tolomeo (1561) and constitutes one of the first dedicated maps of the East Coast. The scope of coverage is extensive, stretching from Labrador and Nova Scotia in the north to Cabo de Santa Maria and upper Florida in the south. Prominently included on the map are iconic locations such as Angoulesme (New York Harbor) and Larcadia (Kitty Hawk).

The early mapping of America’s interior

Ruscelli’s map was built on a predecessor map by Giacomo Gastaldi from 1548. Gastaldi’s map was one of the first serious attempts to delineate North America’s Atlantic coastline. Ruscelli expanded this effort by adding the first interior details, including a network of coastal rivers and one of North America’s earliest depictions of a mountain range.

Among the more notable interior details is a speculative conjunction of the Hudson River with the St. Lawrence. This is a noticeable departure from Gastaldi 1548, which includes the mouths of these rivers but provides no interior configuration and certainly does not join them. Instead, this idea seems to have been introduced by Giovanni Battista Ramusio in his 1556 map of New France. Ramusio likely drew his conclusion based on Cartier’s second voyage, which sailed as far up the St Lawrence River as modern Montreal, which merges with the Ottawa River. The speculative basis on which new ideas such as this were introduced and often accepted speaks to the speed with which the geographical understanding of America was evolving at the time.

A note should also be made about the regional label of Tierra de Nuremberg (a.k.a. Norumbega) along the New York/Connecticut coastline. This toponym first appears on Verrazano’s 1529 manuscript map of America as Oranbega but was since widely adapted as the more familiar term used by Ruscelli and others. The name is supposedly an Algonquian word and was believed by many Europeans to refer to a mythical city of great wealth, a legend comparable to the fabled cities of El Dorado and Cibola. The source of this legend is unknown, but its inclusion on early maps and in early travelers’ accounts prompted a century of endeavors to find it.

Conflating the sources

Ruscelli’s map signaled a significant advancement in American cartography. It was one of the earliest attempts to reconcile the discoveries of Giovanni Verrazano (1520s) with those of Jacques Cartier (1530s and 40s). Thus, we note how many southern toponyms, such as L’Arcadia and Angoulesme, come directly from Verrazano’s accounts. Meanwhile, the names of places further north reveal his influence but are not lifted directly from Verrazano. Examples of the latter include Flora (southern Long Island) and Brisa (Block Island?).

However, while Verrazano was the source for many new additions, we may also lay several oversights and omissions at his feet. Important coastal features such as the bays of Chesapeake and Delaware, Cape Cod, and Boston Harbor are all seemingly absent from Ruscelli’s map. Verrazano’s fear of reefs was the most likely reason for this, which prompted him to sail so far from the shore that such coastal features could not be identified.

The configuration of the coast further north was anchored in Cartier’s voyages, which extended deeply inland along the course of the St. Lawrence but never advanced further south than Prince Edward Island. This physical disconnect between the two primary sources leads Ruscelli to reduce the distance between these areas of mapping and exploration. The result of this contraction is evident when looking at the coast of Maine, which Ruscelli has reduced to a single deep bay (Cape Cod?) and a short stretch of unlabelled coast that leads out to Cape Breton. While one of the unlabelled islands out here may constitute a representation of Nova Scotia, none are labeled, and none take on even a remotely correct outline. Once we move further north into the area explored by Cartier, Ruscelli’s map once again becomes reliable, providing new presentations of the Gulf of St Lawrence, Newfoundland (Terra Nova), and Labrador (Tierra del Labrador).

Concluding remarks

Ruscelli’s “Tierra Nueva” is a cartographic masterpiece and a historical artifact that offers profound insights into the early European exploration and mapping of North America. Its detailed representation of the eastern coastline, combined with its incorporation of significant exploratory discoveries, makes it an invaluable resource for understanding the development of geographic knowledge during this period.

As one of the earliest acquirable maps of the North American East Coast, it remains a foundational piece for collectors and historians, reflecting the dynamic and transformative nature of Renaissance cartography.

Cartographer(s):

Girolamo Ruscelli (1518–1566) was an Italian mathematician, polygraph, and cartographer active in Italy during the early 16th century. He was born around 1518 in Viterbo to a family of minor nobility and humble origins. Throughout his life, Ruscelli moved around, living all over Italy. He started in Aquilea, but his work soon drew him to more important centers of learning. He moved first to Padua, and around 1540, he settled in Rome, where he founded his Accademia dello Sdegno. Around 1545, Ruscelli left Rome for Naples, and in 1548 he finally settled in the city that would make him most famous, Venice.

While posterity primarily remembers Ruscelli as one of the most important cartographers of the Venice School, his primary source of income came from publishing – both his works and copying the work of others. While he wrote on a broad range of subjects himself, the works plagiarised from others were often published by his partner, Plinio Pietrasanta. This lucrative relationship lasted until 1555 when Ruscelli was arrested and tried by the Inquisition for re-publishing a satirical poem by Pietrasanta without his formal permission. Any confrontation with the Inquisition was unpleasant enough, but Ruscelli may have been particularly susceptible to pressure because his wife’s family entertained Protestant sympathies. His brother-in-law was burned at the stake in Rome some years later.

The relationship with Pietrasanta had nevertheless soured, and the publishing firm was soon closed. Instead, Ruscelli partnered up with another Venetian publisher, Vincenzo Valgrisi. It was with Valgrisi that Ruscelli published his famous Ptolemaic Geografia in 1561. This atlas contained sixty-nine engraved maps sporting the latest ideas in Italian cartography. Despite containing some of the latest cutting-edge ideas about the world’s composition, Ruscelli’s atlas also drew heavily on earlier works. Forty of the 69 maps in Ruscelli’s atlas were copied almost directly from Giacomo Gastaldi’s Geografia from 1548.

Despite Ruscelli’s fame as a cartographer, he also achieved considerable recognition under his pseudonym Alessio Piemontese. His greatest success in this regard came the same year as his arrest (1555), with the publication of De Secreti del Alessio Piemontese. In this book of alchemy, Ruscelli reveals himself as a true Renaissance man, dabbling proficiently in multiple disciplines at the same time. His ‘Secrets‘ contained instructions on how to make everything from alchemical compounds and medicines to cosmetics and dyes. The work was so popular that it was re-issued numerous times over the next two centuries, and translated into French, English, German, Latin, Dutch, Spanish, Polish, and even Danish.

Condition Description

Very good.

References