Sebastian Münster’s World Map According to Ptolemy.

Ptolemaisch general Tafel begreifend die halbe kugel der Weldt.

$1,200

1 in stock

Description

A Tribute to the Father of Geography.

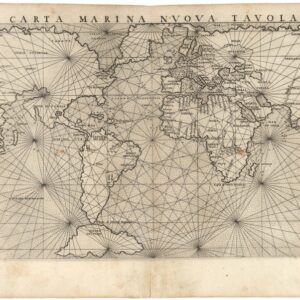

This extraordinary map represents the world as conceived by Claudius Ptolemy, the 2nd-century Roman geographer and astronomer. Created by Sebastian Münster, one of the most influential cartographers and scholars of the mid-16th century, the map offers a striking contrast between the classical geographic worldview and the revolutionary discoveries of Münster’s time.

First published in Münster’s 1540 edition of Cosmographia, this map was included in every subsequent edition of this seminal work. The example presented here originates from the 1567 German edition.

The map provides an invaluable historical perspective on world geography, tracing how Ptolemaic geography persisted from Antiquity through the Middle Ages. It was only during the Renaissance, with the groundbreaking discoveries of the 15th and 16th centuries, that this ancient understanding was finally challenged and replaced. As a result, Münster’s map serves as a retrospective piece, capturing a turning point in geographic thought at a time of significant intellectual upheaval and exploration.

The Original Source

Münster based this map on the works of Claudius Ptolemy, whose geographical writings were rediscovered in the 14th century. The map details the Oikoumene, or the inhabited world, as understood at the height of the Roman Empire. It extends from the Atlantic Ocean to Southeast Asia, and from the Arctic north to the Tropic of Capricorn in the south.

Using a conic projection, which was a common cartographic technique at the time, the map adheres to Ptolemy’s tripartite division of the world into three continents: Europe, Africa, and Asia.

1. In the upper left, Europe is depicted in a recognizable form.

2. Below, an enormous Africa stretches into the unknown. Although much of the continent remains largely speculative, Münster includes two great rivers—the Nile and the Niger—as well as the mythical Montes Lunae (Mountains of the Moon), which ancient scholars believed to be the source of the Nile. These mountains appear at the bottom of the map but are left unlabeled. Despite limited knowledge, Münster incorporates Ptolemaic place names, such as Meroë, while others, such as Arabia Felix, reflect the long-standing trade relationships between the Roman world and these distant regions.

3. Asia, by far the largest of the three continents, remains highly fragmented in terms of knowledge. It includes notable misconceptions inherited from Ptolemy, such as an oversized Sri Lanka (Taprobane) and an almost nonexistent Indian Subcontinent. These distortions arose from the close mercantile ties between Rome and Sri Lanka, which were better documented than the rest of South Asia. Other features typical of the Ptolemaic worldview include the rectangular Persian Gulf and the conflation of India and the Malay Peninsula.

Perhaps the most significant feature of the map is its depiction of the Indian Ocean as a closed sea, completely enclosed by a massive, unexplored southern continent. According to Ptolemaic theory, this mythical landmass was believed to balance the northern continents and prevent the Earth from tipping over. This idea remained a dominant feature in European cartography until the late 16th century, when circumnavigations of the globe proved otherwise.

While Münster intentionally aimed to convey an ancient worldview, he also introduced elements unknown to Ptolemy. The most striking example is the large Scandinavian landmass extending into the Arctic, reflecting the growing cartographic interest in northern Europe following the pioneering efforts of Claudius Clavus and Olaus Magnus in the 15th century.

Why a Retrospective Map?

Münster’s decision to include this ancient geographic representation in his otherwise modern Cosmographia highlights the enduring influence of Ptolemy’s work on Renaissance geography. Although Ptolemy’s system consisted primarily of coordinate-based descriptions of places, there is no evidence that he ever produced an actual map. The visual representations we associate with Ptolemaic geography emerged only after his works were rediscovered and reinterpreted in a period of rapid global exploration.

This revival of Ptolemaic geography coincided with the development of the printing press, a serendipitous event that transformed mapmaking forever. Münster’s work, therefore, was not just a reproduction of an ancient worldview but a testament to the evolution of geographic thought.

Sebastian Münster was not merely a Renaissance polymath—he was a visionary cartographer. His ambition was to map the entire known world, and as global discoveries continued to expand Europe’s understanding of geography, Münster actively updated his works. This ambition is evident in his Cosmographia, which introduced revised maps of Asia and Africa, along with the first printed map of the American continents.

The inclusion of a Ptolemaic world map was more than just a contrast between the old and the new—it was a tribute to the man who laid the foundations for modern geography. By incorporating this historical reference, Münster provided readers with a visual tool for understanding how far geographical knowledge had advanced in the 16th century.

Publication information

This map was first published in Münster’s 1540 edition of Cosmographia and remained a fixture in all subsequent editions until 1578. After Münster’s death, new posthumous editions of the Cosmographia were published by Sebastian Henricus Petri. From 1588 onward, these later editions were updated with woodcut maps based on the geography of Abraham Ortelius, reflecting a more modern perspective.

While all editions of Münster’s Geographia were printed in Latin, the Cosmographia was published in Latin, German, French, and Italian, broadening its reach across Europe.

The present example originates from the 1567 German edition of Cosmographia.

Cartographer(s):

Sebastian Münster (1488-1552) was a cosmographer and professor of Hebrew who taught at Tübingen, Heidelberg, and Basel. He settled in Basel in 1529 and died there, of the plague, in 1552. Münster was a networking specialist and stood at the center of a large network of scholars from whom he obtained geographic descriptions, maps, and directions.

As a young man, Münster joined the Franciscan order, in which he became a priest. He studied geography at Tübingen, graduating in 1518. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Basel for the first time, where he published a Hebrew grammar, one of the first books in Hebrew published in Germany. In 1521, Münster moved to Heidelberg, where he continued to publish Hebrew texts and the first German books in Aramaic. After converting to Protestantism in 1529, he took over the chair of Hebrew at Basel, where he published his main Hebrew work, a two-volume Old Testament with a Latin translation.

Münster published his first known map, a map of Germany, in 1525. Three years later, he released a treatise on sundials. But it would not be until 1540 that he published his first cartographic tour de force: the Geographia universalis vetus et nova, an updated edition of Ptolemy’s Geography. In addition to the Ptolemaic maps, Münster added 21 modern maps. Among Münster’s innovations was the inclusion of map for each continent, a concept that would influence Abraham Ortelius and other early atlas makers in the decades to come. The Geographia was reprinted in 1542, 1545, and 1552.

Münster’s masterpiece was nevertheless his Cosmographia universalis. First published in 1544, the book was reissued in at least 35 editions by 1628. It was the first German-language description of the world and contained 471 woodcuts and 26 maps over six volumes. The Cosmographia was widely used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and many of its maps were adopted and modified over time, making Münster an influential cornerstone of geographical thought for generations.

Condition Description

Hand color. Visible repairs, as seen on the image. Overall nice.

References

![[Dr. Seuss] This Is Ann….. She Drinks Blood!](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NL-01354_thumbnail-300x300.jpg)