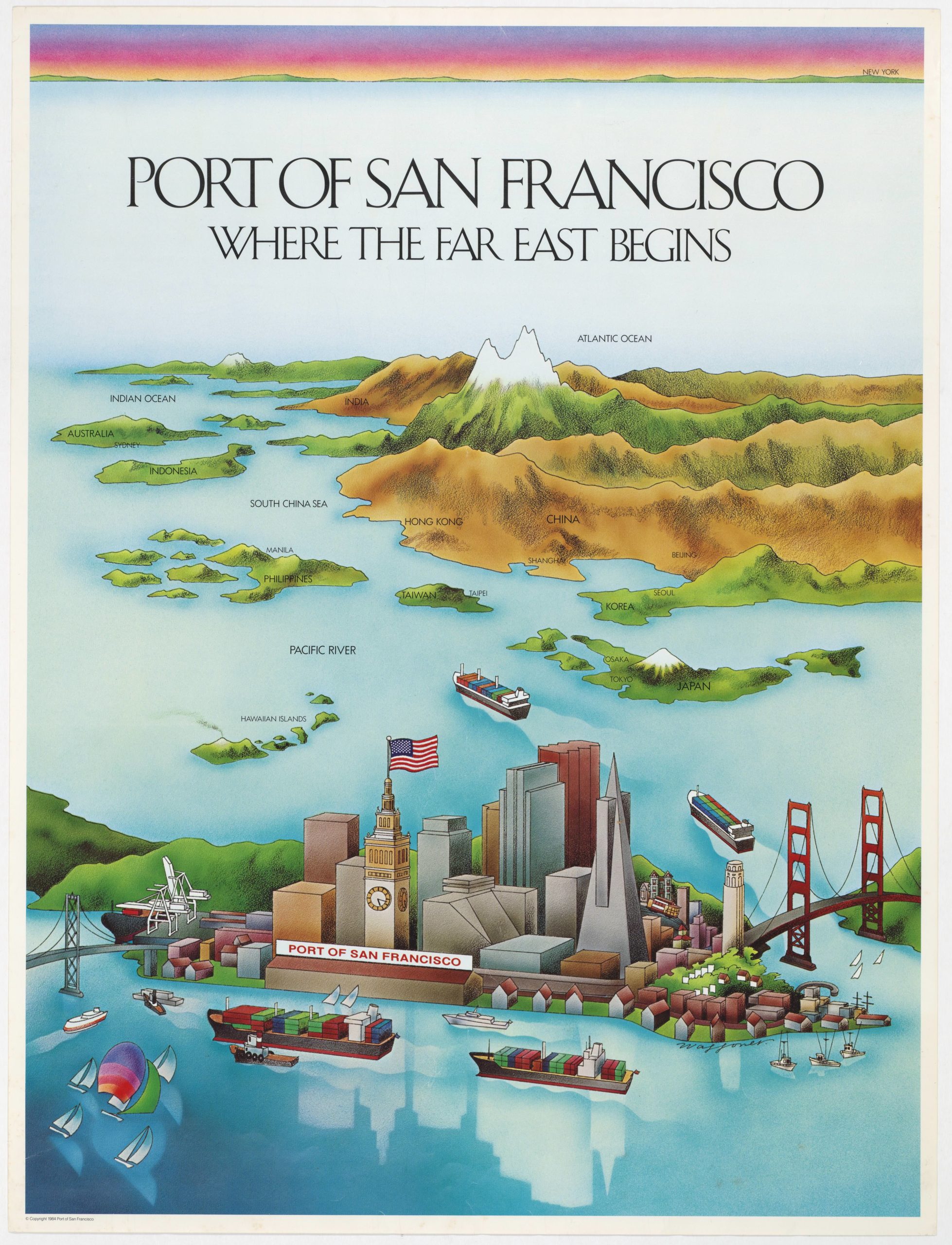

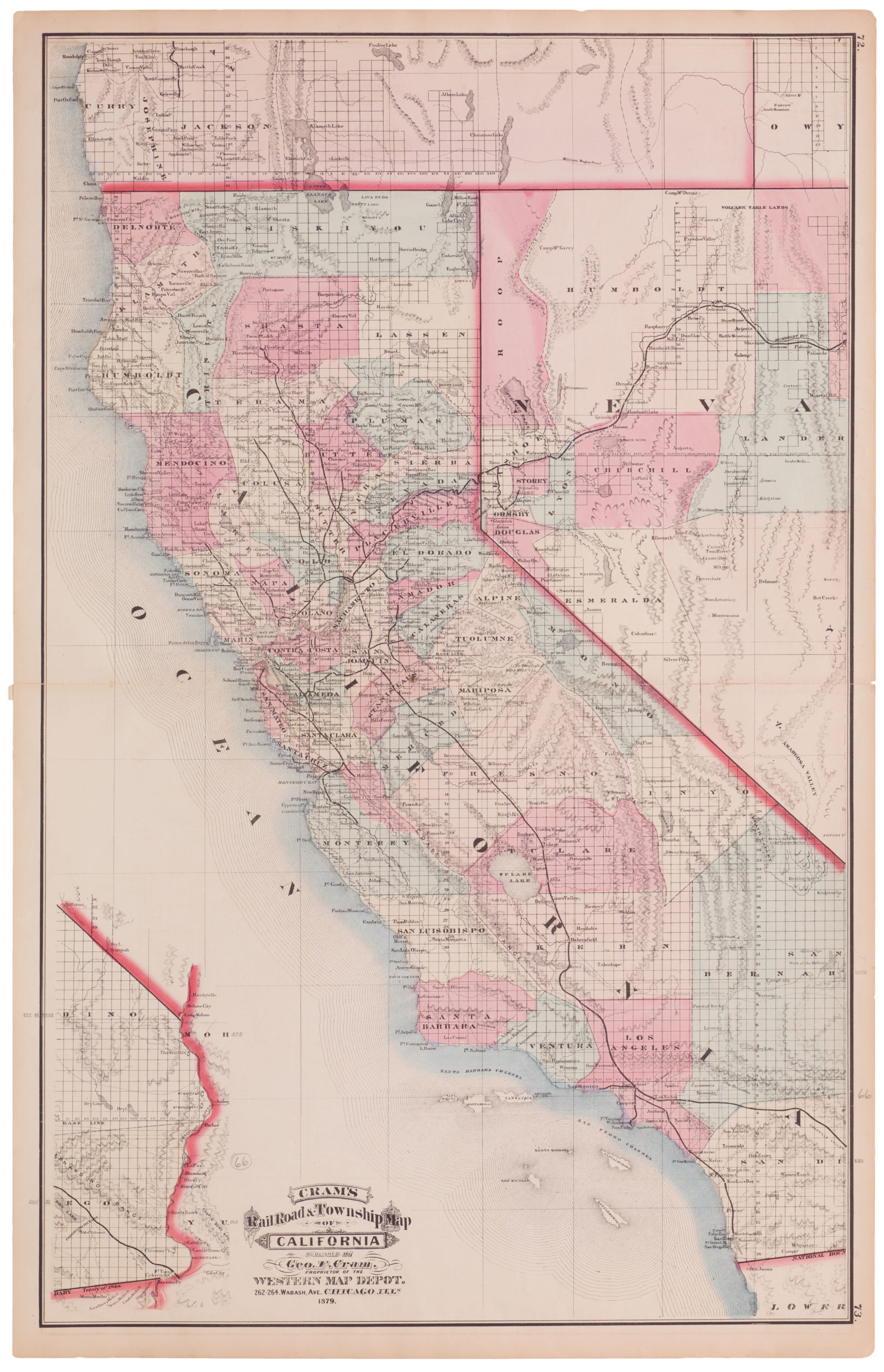

One of the most fantastic and interesting early maps of California ever to be produced!

Granata Nova et California

Out of stock

Description

Three factors make Wytfliet’s 1597 map of California and the west coast a seminal cornerstone work in the cartography of the region:

- It is the earliest obtainable regional map of California, with all other examples being manuscript maps held in libraries or works in private collections.

- It is one of the earliest known portrayals of the Colorado Delta, where the Colorado River meets the Gulf of California.

- It is the most important regional map to portray California as a peninsula; shortly after its publication, the mythological Island of California would dominate the cartography of the region for centuries.

The map was published in the first printed atlas to depict North America regionally. It arrived in the window between Hernan Cortés and Father Antonio de Ascension; Cortés fervently believed that California was an island and launched or sponsored a series of explorations between circa 1520-40 to prove this belief, but then the notion fell out of favor until it was revived by Ascension’s account of the Vizcaino expedition, published in 1613. As a result, Wytfliet’s overall geography is more accurate than some maps that came centuries later, even maps made by some of the most accomplished figures in the history of cartography.

The Sea of California is named Mer Vermeio (Red Sea), in accordance with descriptions provided by Cortés and his lieutenants. The Baja Peninsula is annotated with toponyms that demonstrate the strong Spanish presence here; however, as one might expect, there are fewer attributions as one moves up the west coast towards Alaska. The place names are a mix of early Spanish designations and common 16th century cartographic misconceptions. One example is ‘Capo del Engaño’ (‘Cape of Disappointment’ or ‘Deceit’), so named by commander Francisco de Ulloa in 1540 because it was at this latitude that he expected (and failed) to find the north end of the Island of California.

One of the reasons that the earliest Spanish explorers had such a hard time in determining whether California was an island or not is that the northern end of the Gulf of California, where a definitive observation may have been possible, was a confusing place for early ship captains, who did not understand the powerful forces and the massive extent of Colorado River Delta. The meeting of the two waters results in a dangerous tidal bore, which time and again forced early expeditions to retreat. That delta is represented on Wytfliet’s map by means of a stippled pattern, constituting one of the earliest depictions of this key natural feature on any map.

Multiple large rivers extend inland from the Gulf of California, several of which link up to mountain ranges. One is most certainly the Colorado River. There is also a common error found on maps of the region published in the 16th and 17th centuries (it was not until Nicolosi’s seminal maps that the error was corrected). A large river, which many see as an erroneous depiction of the Upper Rio Grande, flows into the Gulf of California from the area of present-day Arizona and New Mexico.

This river is fed by a large lake surrounded by seven villages or settlements. These seven settlements (Septem civitatum Patria) refer to the legend of Cibola and the Seven Cities of Gold, an extremely popular myth in the 16th century, and the aim of many a fortune-seeking conquistador. The origins of the myth are elusive but it gained serious popular momentum thanks to Franciscan friar Marcos de Niza. De Niza was sent north from Mexico City by Viceroy Mendoza in 1538-39 to search for wealthy cities that were rumored to be somewhere past the northern frontier of New Spain. In early 1539 he left the frontier at Compostela and journeyed into the unknown. In the summer of 1539 he returned and wrote a report stating that he had discovered the cities in a province called Cibola (the present-day native American pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico). He related that he reached the first city and saw it from a distance, but because his companion had been killed there, he returned without entering it.

Most popular writers claim De Niza reported gold in Cibola, but his original report says nothing about gold. Nonetheless, conquistadors in Mexico City were excited by his news and assumed Cibola would be as wealthy as the great cities of the newly-conquered Aztec empire. This stimulated a frenzy of expeditions, none of which were successful in penetrating deep enough inland to locate any hidden cities. In 1540, De Niza led Coronado’s army back to Cibola, but he became the scapegoat when Cibola turned out to have no golden cities, just numerous villages built in adobe.

Coronado’s soldiers accused De Niza of being a liar, but the allure of such myths and the lust for treasure nevertheless led to renewed pushes inland, which in turn provided fresh data, however spurious, for cartographers. The mythical cities represented on Wytfliet’s map are thus representative of the late 16th conception of the American West, an area still very much on the frontier of cartographic knowledge.

Cartographer(s):

Cornelis van Wytfliet (died around 1597) was a geographer from Leuven in the Habsburg Netherlands, best known for producing the Descriptionis Ptolemaicae augmentum sive Occidentis notitia brevis commentario, as a supplement to Ptolemy’s Geographia.

‘Descriptionis‘ was published in Leuven in 1597 and is considered the first atlas devoted exclusively to the New World. It featured nineteen maps: one world map and eighteen regional maps. The regional maps, in particular, are notable as early representations of specific areas of North and South America.

Condition Description

Very good. Minor repair to top margin.

References

Burden #106; Heckrotte #7; Wheat (TWM) #29; Wagner #188.