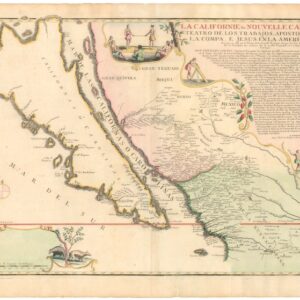

De Wit’s superb western hemisphere with carte-à-figures and Island of California.

Nova Totius Americæ Descriptio

Out of stock

Description

Uncommon, separately published, and attractive map of North and South America, with California as an island and a border comprised of engravings of cities at the top and a series of representations of native figures at the sides, including two from Virginia.

Burden describes it thus: “Frederick de Wit’s first map of America was not intended for any specific atlas, although it is sometimes found in the Zee-Atlas of Hendrick Doncker. Together with its desirability as an example of a carte et figures, it is relatively uncommon… The map is a blend from many different sources, which gives overall an appealing look. The decorative borders are taken from Van den Keere, 1614, although fewer towns are illustrated.”

The map is comprised of an amalgam of sources. The decorative figures at the sides of the map derive from Van den Keere’s map of 1614. The model for the island of California is based upon a rare English map by Luke Foxe, but the contiguous coast of the mainland from Foxe’s map is inadvertently engraved as a river. Hudson’s Bay & the Great Lakes are derived from Blaeu. New Amsterdam is shown, but no evidence of English settlements.

The depiction of California as an island, the cartographic enigma celebrated collectors and scholars alike, began in earnest around the 1620s, when it appeared on printed maps. The notion developed following early Spanish expeditions up the Pacific coast. In particular the writings of a Carmelite friar, Antonio de la Ascension, seem to have promulgated the idea among Spanish mariners and cartographers, and from here it soon spread to the formerly Spanish domain of the Netherlands. Throughout Europe, the competitive cartographic markets hungered for fresh information on the new world, and often ideas would be incorporated without much critical verification. It was all about being first.

The California-as-an-island idea had thus been well established by the time De Wit compiled his charts. Important predecessors such a Hendrik Hondius, Nicolas Sanson, and John Speed had all been taken in by the notion and included it prominently in their charts. It was, in other words, neither strange nor out of place for De Wit to follow in this tradition. In many ways, this De Wit map represents a unique point in time in which the geographic myth had transcended into cartographic reality, and before it was first debunked by Father Kino, who travelled the Pacific coast and verified the peninsular nature of California himself. Kino published his observations in Paris in 1705, but the insular depiction was continued well into the 18th century.

For its part, South America seems to have been portrayed in full, but there are still many aspects of its depiction that reveal it to be riddled with speculation and mythology. Highly important is of course the depiction of Cape Horn, as this was the only known route from the Atlantic to the Pacific at the time.

While still a largely unexplored region at the time, the Amazon includes an extensive network of rivers extending from the unknown interior to their various deltas on the coast. As waterways constituted the only transportation infrastructure through the dense vegetation, it is no surprise that rivers were the most accurately marked out physiographic features on the map. Indeed, prior to the Portuguese and English pushing them out of the region, the Dutch had entertained huge imperial ambitions for Brazil.

An interesting inclusion, albeit hardly unique for the time, is the depiction of Lake Parime in modern Guyana. This mysterious lake has been repeatedly associated with the legend of Eldorado; a city of gold supposedly located on its shores. While there exists no historical or archaeological data to corroborate that such a place ever existed, the myth has been both long-lived and extremely tenacious. Obviously, the notion must have sprung from the immense wealth that the conquistadors brought back from the New World. The opportunities that this new and vast territory afforded attracted many adventurers and opportunists, to whom history’s judgment has not been very kind.

The notion was nevertheless pervasive. So much so that expeditions continued to be launched well into the 20th century (e.g. Colonel Percy Fawcett). The most infamous expeditions to find the mystical city of gold were perhaps those lead by Sir Walter Raleigh, the close confidant and advisor of Queen Elizabeth I. Raleigh made several attempts to find Eldorado: the first in 1594 and a second in 1617 (under King James I). Both attempts failed miserably and when Raleigh against orders raided a Spanish galleon on his second voyage, he was recalled by King James and executed.

This is the second state of the map, with the 1660 date erased from the title.

Cartographer(s):

Frederick de Wit (1629–1706) was a Dutch cartographer and artist who drew, printed, and sold maps from his studio in Amsterdam. He was a pioneer of Dutch Golden Age cartography, and the founder of one of the most famous map-publishing houses in Amsterdam. He was born in Gouda but moved to Amsterdam at the end of the Thirty-Years-War (1618-48), which had engulfed most of Europe and ultimately liberated the Netherlands from centuries of Spanish dominion.

Soon after arriving in Amsterdam, probably in 1654, De Wit opened a printing shop named The Three Crabs (De Drie Crabben). A year or two before, he had married Maria van der Way, the daughter of a wealthy Catholic merchant, and this may have helped secure the funding to start his new operation. His aspirations as a cartographer were nevertheless made clear when he shortly after changed the name to The White Chart (Het Witte Pascaert), under which he gained international renown.

In the latter half of the century, De Wit began drawing, copying, and publishing atlases and maps. By the 1670s he was issuing large folios with up to a hundred maps in each tome, including a famous nautical atlas in 1675. From 1689, De Wit received a state privilege from the Dutch government to draw and issue maps. This protected his work from the illegal copying known from his earlier charts. De Wit was among the first to apply extensive coloring and his original color atlases and continental charts remain highly sought after to this day.

Following De Wit’s death in 1706, his wife ran the business for four years before selling it at auction in 1710. Their only surviving son was a successful merchant in his own right and had no interest in taking over. At the 1710 auction, most of De Wit’s plates were sold to Pieter Mortier, another Amsterdam cartographer and engraver. After passing the firm to his son, who teamed up with Johannes Covens, the firm became Covens & Mortier, the largest cartographic publisher of the eighteenth century.

Condition Description

Some minor soiling, map verso darkened, a few short marginal tears; The word "L'Amérique" has been boldly inked in top margin.

References

Burden 356; Leighly 40; McLaughlin 24; Wagner 385b.