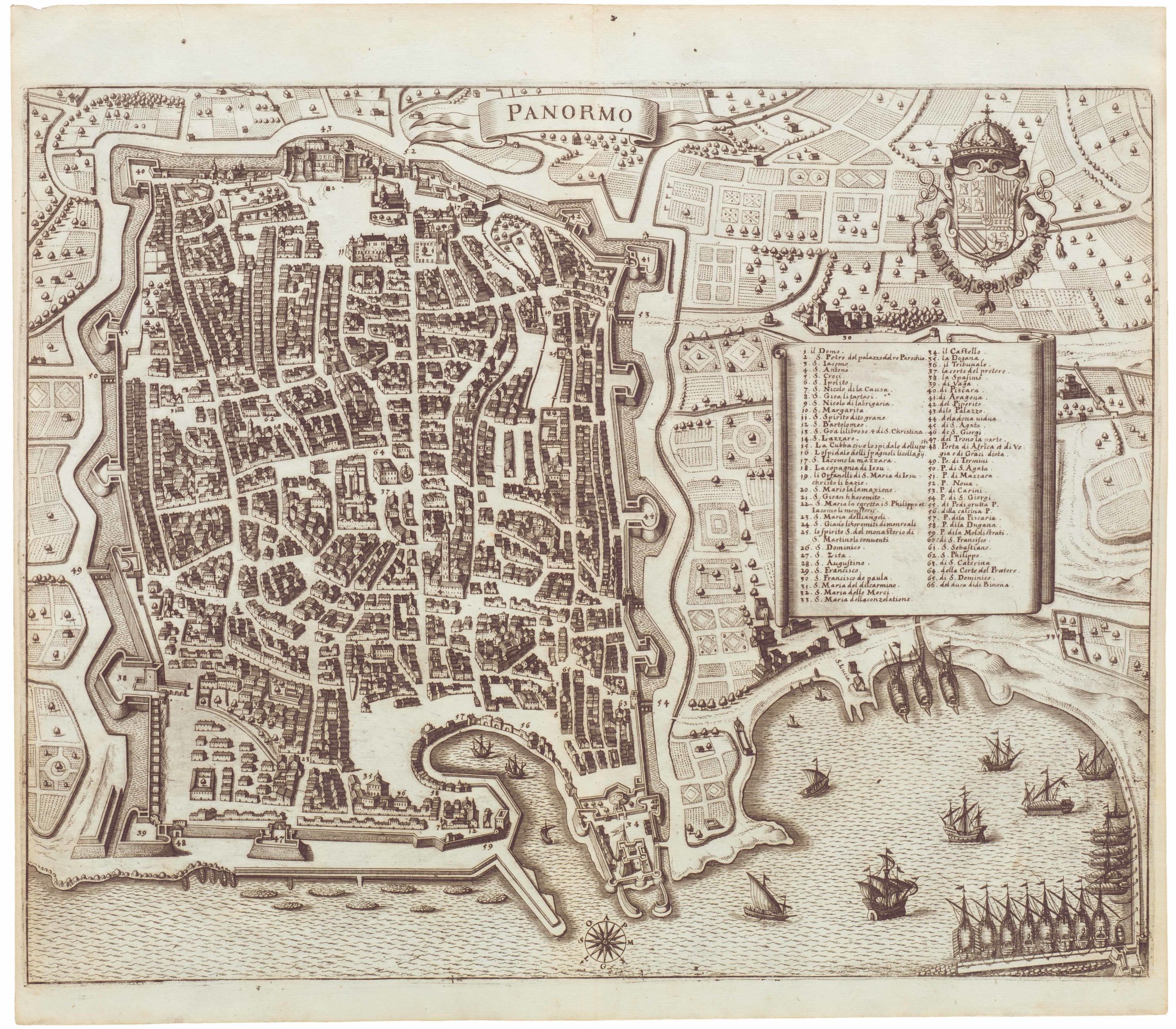

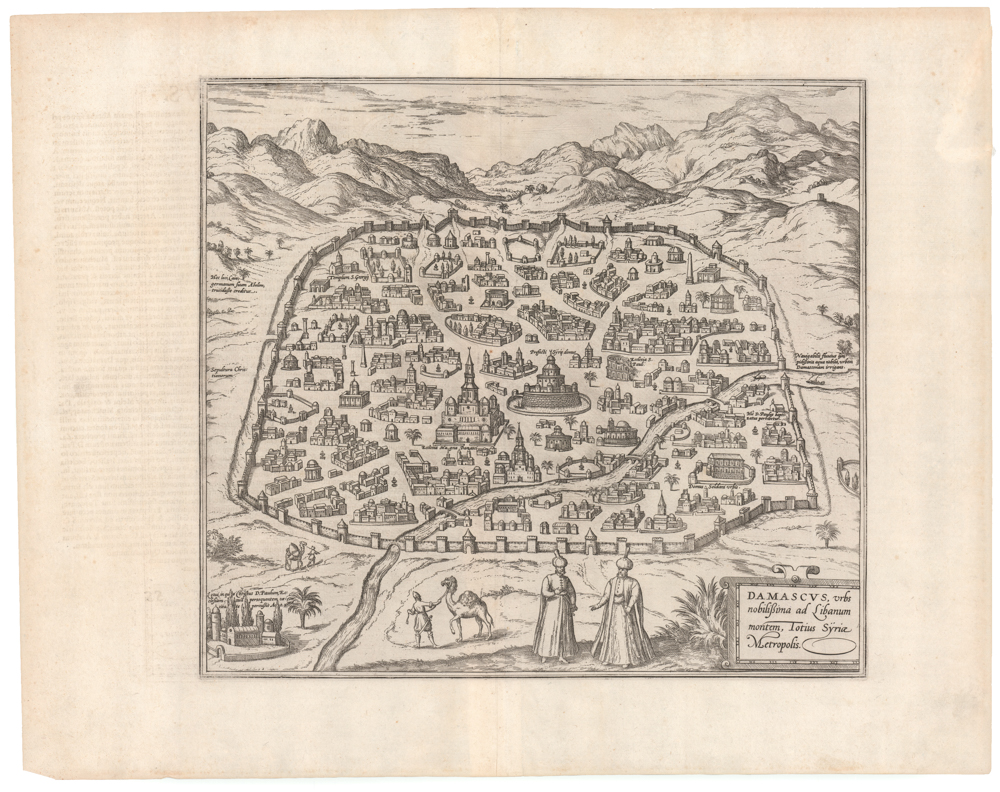

Lafreri-school rendition of Süleyman the Magnificent’s capital.

Constantinopoli

$4,200

1 in stock

Description

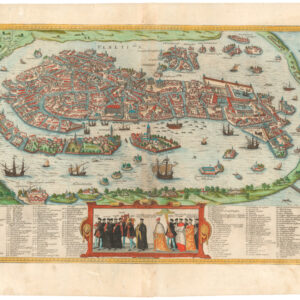

Claudio Duchetti’s panorama of Constantinople presents the city as seen from the heights of Üsküdar (Scutari) on the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus. The engraving unfolds a continuous sweep from the fortified ramparts of Pera, across the Golden Horn to the silhouette of the Seraglio Point, and thence along the Sea of Marmara to the harbor mouth. Duchetti renders the city’s famously impenetrable walls, battlements, and towers in clear profile; mosques and palaces rise above clusters of dense urban blocks, domes and minarets punctuating the skyline. The strait is animated with galleys and sailing vessels, underscoring Constantinople’s role as a maritime hub between Europe and Asia. A 16‑point compass rose in the Sea of Marmara reflects a Venetian mapping convention in which the rose is oriented with north‑west toward the top of the sheet.

Duchetti’s view generally follows the cartographic template established by Andrea Vavassore’s early sixteenth‑century woodcut (c. 1520–30), which in turn drew on a lost drawing that Giovanni Domenico Zorzi (Domenico delle Greche) made during the last years of Mehmet II’s reign. The broad, elevated perspective and arrangement of key landmarks owe much to Vavassore, although Duchetti refines the view with a sharper engraving and updates to the harbor quays. Presumably, vignettes in works by Paolo Forlani, Ferrando Bertelli, and Zenoi also inspired Duchetti’s pleasing composition and detail.

Below the panorama, a numerical legend identifies 58 sites. Divided into six narrow columns, it references everything from the Hagia Sophia (35) to the Arsenal (16) and the Ottoman Sultan’s Topkapi Palace (24). The extensive key underscores that the map was both ornamental and utilitarian.

Duchetti merges the cartographic heritage of Andrea Vavassore with the flourishing print culture of the Lafreri school. In doing so, he offered Renaissance Europe an evocative window onto the Ottoman capital. With its precise engraving, systematic legend, and elegant merger of prior models, Duchetti’s bird’s‑eye view is one of Constantinople’s finest 16th-century representations.

A jewel to rival oneself: The glorious capital of Süleyman the Magnificent

Under Süleyman’s reign (1520–1566), Constantinople’s skyline was radically recast to express Ottoman imperial power and Islamic piety. At the heart of this transformation was the Süleymaniye Mosque complex on the city’s Third Hill, built by his chief architect Mimar Sinan between 1550 and 1557. The mosque redefined the city’s profile with its massive central dome flanked by semi‑domes, four slender minarets, and a raised terrace overlooking the Golden Horn. Around it, Sinan laid out a full külliye, or charitable foundation, comprising a madrasah (theological school), a darüşşifa (hospital), an imaret (soup kitchen), a caravanserai, and a hammam (bathhouse). This ensemble provided social services to thousands of people and set a model for Ottoman urban planning, in which religious complexes defined neighborhoods by ordering streets, markets, and public spaces.

Beyond monumental mosques, Süleyman’s building campaigns repaired and extended the city’s infrastructure and amenities, reinforcing Constantinople’s role as the empire’s thriving capital. He had the ancient Theodosian Walls strengthened and gates like Yedikule refurbished, improving defense in a period of Ottoman‑Habsburg rivalry. He restored aqueducts – most notably the Valens line – to ensure a steady water supply to his new külliyes and growing population. He patronized the expansion of covered bazaars, including the spice and silk markets, integrating commercial quarters more tightly into the urban fabric. Each külliye was complemented by public baths, fountains, and caravanserais, reflecting a new pattern of Ottoman urbanity.

Census

Duchetti (d. 1585) inherited half of Antonio Lafreri’s plate collection and operated in Venice from 1565 to 1572, before moving his workshop to Rome, where he remained active until his death. His imprint – Per Claudio ducheto 1570 – is found at the lower right base of the plate, marking the present example as a rare first state of the engraving. In the same corner, the interlaced monogram IAF identifies Giacomo Franco as the engraver. The sheet bears a shield‑and‑star watermark, typical of Venetian laid papers of the period, confirming a print date around 1570.

Duchetti himself printed only a single state of this view in 1570. However, the plate had several owners after that. By 1598, it had entered the inventory of Giacomo Gherardi (as Constantinopoli Reale), and in 1602, Giovanni Orlandi reissued it, adding his own imprint on the verso. Francesco de Paoli acquired the plate in 1633, though no further states are recorded.

The first state is rare, with the OCLC listing only three institutional examples (234170896).

Cartographer(s):

Claudio Duchetti was a prominent Italian engraver and print publisher based in Rome during the late 16th century. Active from around the 1570s to the 1580s, Duchetti came from a notable family of printmakers. He was the nephew of Antonio Lafreri, a highly influential figure in the Roman print trade. After Lafreri’s death in 1577, Duchetti continued the family business and became one of the key figures in the production and distribution of prints in Rome. His workshop was known for producing engravings of maps, classical antiquities, religious subjects, and popular imagery, catering to the growing demand for printed material during the Renaissance.

Duchetti’s prints often reflected his time’s intellectual and artistic currents, appealing to scholars and collectors interested in Italy’s classical heritage. His work contributed to the spread of visual culture across Europe and was part of the more significant movement of cartography and printmaking that characterized the late Renaissance. Although he did not achieve the same lasting fame as Lafreri, Duchetti’s role in maintaining and expanding the family print business established him as a significant figure in the history of Roman publishing.

Condition Description

Excellent impression on thick paper. Small restoration on right side, expertly done; for the rest, excellent conservation.

References

Tooley, Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century, 156 I/II; Meurer, The Strabo Atlas, 166; Franco, Novacco Map Collection, 114.