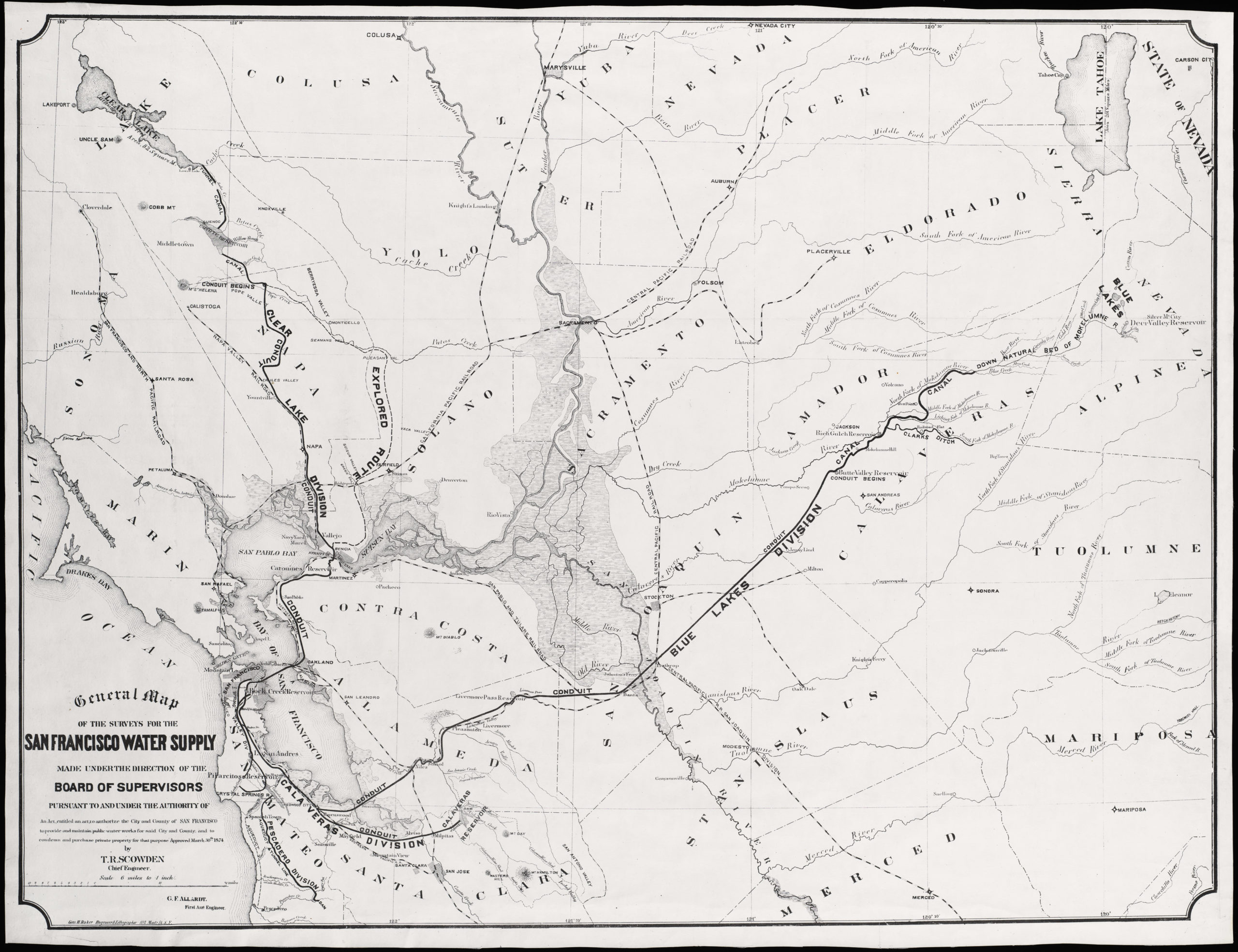

An urban panorama unlike any other: documentation of the devastation caused by the 1906 earthquake and fire.

[1906 EARTHQUAKE PANORAMA – FINANCIAL DISTRICT]

$3,400

1 in stock

Description

This incredible panorama provides a horrifying view across downtown San Francisco and the Bay, with Union Square and Stockton Street at the built up center of the photograph. Being a composite panoramic image, the view stretches from Telegraph Hill and in the left of the image, to Bernal Heights in the right. An annotation at the bottom of the image reveals that it was taken from the roof of the St. Francis Hotel on Nob Hill.

The massive devastation that the city suffered is clear from the image. With a few skeletal exceptions, most of the horizon simply consists of rubble; a landscape of flattened structures of which there is next to nothing left. The more monumental and sturdy buildings visible in the front of the image are mostly ghostlike shells, reminiscent of the bombed out German cities at the end of the Second World War. Consequently, discerning some of the features described here can be difficult.

The combination of the earthquake and the subsequent fires meant that 80% of the city was completely destroyed. When one looks at these images, there is little doubt this is true. Even the buildings that remained standing, had in most cases suffered such serious damages that the only option was to demolish and build anew. There are nevertheless subtle glimmers of hope in the field of ruins: features that would become urban emblems linking San Franciscans with their past.

At the front and center of the image we have the built up area surrounding Union Square. Many of the visible buildings were in fact under construction when the earthquake hit. Standing tallest is the Call Building, built in the late 1890s by John D. Spreckels as his father Claus Spreckels to house their newly acquired paper, The San Francisco Call. Conceived and built by architects Reid & Reid, the tower stood 315 feet tall and was crowned by an ornate baroque dome flanked on each corner by a smaller dome. Upon its completion, it was the tallest building west of the Mississippi and an icon of Californian modernity. The building was badly damaged during the earthquake and subsequent fires, but as is evident from the photo, it remained standing and intact. The building still exists today as the Central Tower (703 Market Street), although an extensive refurbishment in 1938 reduced its height and removed the magnificent domes.

In roughly the center of the panorama, in the lower ruin fields just right of the Call Building, we see the darkened remains of the massive brick tower of the Cable Car Powerhouse on Pacific Avenue, which succumbed almost completely to the tremors. From here, there is a view down Market Street, Van Ness Avenue, and all the leveled neighborhoods in between them. After the earthquake, the axes of both Market Street and Van Ness became key thoroughfares in the urban infrastructure: a means of getting supplies in and out of downtown. Soon Market Street also became famous for one of its monuments, Lotta’s Fountain; a twenty-four foot cast-iron fountain, which in the aftermath of the earthquake served as a meeting point for people who had been separated from each other in the chaos. To this day, San Franciscans gather at Lotta’s Fountain in the early hours every April 18th to mark the tragedy.

Even though the Call or Spreckels Building undoubtedly was a San Francisco landmark at the time, the best-known pre-earthquake building still standing today is perhaps the Ferry Building, on Embarcadero and Market Street. Because of the photographer’s vantage point and the haze of smoke still hanging in the air, the building is barely visible down by the waterfront, but it too served as an important gathering point in the aftermath of the earthquake, as well as a means for civilian fire brigades to identify new fires throughout the northern part of the city.

The most imposing and important civic monument to survive the earthquake was the Old Mint, a massive sandstone structure set on a solid base of concrete, which protected it from the tremors. The enclosed courtyard in its center contained its own well, which helped prevent the ubiquitous fires from taking hold in the building. Its salvation was of crucial import, both as a symbol, but also because about one third of the United States gold bullion was kept here. It is only barely visible in the photograph as a large dark-grey mass along the southern flank of Market Street, but stands out clearly on the smaller image.

Despite the ominous and tragic background for this panoramic image, one senses that life gradually is returning to normalcy: a testament to just how resilient the inhabitants of San Francisco were. Ships are approaching her harbor and her streets are filled with cars, horses, pedestrians, carts, and even the famous trams.

In the far left of the image, with the Telegraph Hill in the background, we see a large sandstone church that has been left largely intact. The iconic remains of Temple Emanu-El, Grace Cathedral behind it, and St. Mary’s to the right are all visible. Nearby stand the sorrowful ruins of the Palace Hotel, San Francisco’s most celebrated hotel and a landmark in and of itself.

Background

Essentially, this is an image of a city destroyed. It conveys with uncompromising clarity the magnitude of destruction and suffering following the 1906 earthquake. Consequently, it might be helpful to provide a little background on the earthquake meant and what it meant for the history of San Francisco.

The San Francisco earthquake struck in the early morning hours of April 18th 1906. It preceded the Richter scale by which we measure earthquakes today by three decades, but calculations have since shown that its force would have been equivalent to about 7.9 on the Richter scale and a Mercali Intensity of XI (extreme). Soon after the tremors had abated, more than thirty fires broke out across the city and raged for four days. Most of these were caused by the raptured gas mains, but in some cases they were inadvertently started by local firefighters. The fires burned intensely hot and since most residential buildings were built of timber and brick, entire neighborhoods burned completely to the ground. It has been estimated that 90% of the total destruction caused by the earthquake resulted from the fires.

When it was all over, more than 80% of the city had been destroyed and more than 3000 people had lost their lives. The quake was felt as far away as Nevada, Oregon, and Los Angeles. Modern seismologists still debate the exact epicenter, but most agree that it was just off the coast, northwest of the Golden Gate. The extent of the damage meant that two thirds of the population became refugees overnight, and tents and shacks soon began to shoot up in the Presidio, Golden Gate Park, and North Beach. Eventually, many of the refugees moved across the Bay to Oakland and Berkeley. Important San Francisco landmarks were lost, including the famed Palace Hotel and old City Hall.

In addition to the immediate and short-term impact on the city, the earthquake also had long-term consequences. In 1906, San Francisco was not only the largest and most populous city on the West Coast, but it was also the most important port and bridgehead for American mercantile interests in the Pacific and Asia. Much of this dynamism was lost due to the earthquake. The sheer destruction of basic infrastructure and the chaotic conditions to supply a work force made maritime engagements difficult. As a result, a lot of trade was diverted south to Los Angeles, and with it followed money and people. In effect, and despite an impressively efficient rebuilding process, San Francisco lost its position as California’s major urban center to Los Angeles, and would not regain it again. This shift has come to characterize San Francisco and most of its contemporary inhabitants would have it no other way. Yet it is a powerful reminder of how easily trajectories change.

The process of rebuilding the city was a long and arduous one. While civic leadership began planning the process immediately, finding the necessary funding proved extremely difficult. There was only a single bank in San Francisco that was willing and able to provide the scope of funds needed for the extensive re-building plans. The Bank of Italy had been founded by Amadeo Giannini, an Italian immigrant who had settled in North Beach. He became a great patron of the reborn San Francisco, providing the city itself with much-needed loans and paying for building materials from his own pocket. Years later, the bank would be renamed Bank of America, which it still is known as today.

Due to the nature of the devastation and the difficulties in acquiring both funds and materials for the rebuilding, the process took time. But by 1915 the city had recovered to such a degree that it hosted the Panama Pacific International Exposition; a world fair that celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal that summer. This event showcased the city as a hub of modernity where one could experience the concrete results of technological advancement (incl. a cross-country phone line and the actual Liberty Bell). The exposition proved beyond any doubt that San Francisco had regained its former glory and perhaps now even outshone its former self. For the occasion of the exposition, a glamorous and monumental neighborhood of representative pavilions was constructed along the northern waterfront. Not much remains today, so to get a glimpse of just how impressive the new San Francisco would have been, we are relegated to the Palace of Fine Arts, the most important and imposing of the exposition buildings still standing.

Cartographer(s):

The Pillsbury Picture Company was founded in the spring of 1906, just a month before the earthquake hit. Its serendipitous timing propelled the company to fame and made the Pillsbury stock relevant across America and the world. It was founded by Arthur C. Pillsbury, a disgruntled photojournalist, after he quit his job with the San Francisco Examiner. Pillsbury was renowned for his innovative approach to photography and visual communication. Part of Pillsbury’s success in the wake of the catastrophe was that the company was based in his Oakland home. Here he had set up equipment and darkrooms and could run the entire operation. Because his company, unlike most official press outlets, was not based in San Francisco proper, Pillsbury was quickly able to corner the market. His innovative approach to photography no doubt helped him cement that position.

Pillsbury became famous through his images, but locally he had also won recognition as an uncompromising and innovative photographer. He had made his way into the city admits the ongoing aftershocks and was consequently able to circulate some of the earliest images of the calamity. Pillsbury made a significant amount of money on his earthquake images; in particular his early photos were highly sought after by newspapers around the world. The money he earned from these photographs was spent building his new Three Arrows studio in Yosemite.

Over time, the Pillsbury Picture Company became the largest distributor of post cards on the west coast and later went into film production as well (including the first time-lapse and underwater films). Pillsbury also went on to develop his own cameras, often refusing to patent innovations, because he wanted his inventions to benefit all photographers. In general, Arthur C. Pillsbury was one of the most innovative and productive geniuses in America when it comes to photography and film. His legacy is one of accomplishment, and since it all began with the 1906 earthquake, he has come to represent the resilience and greatness of San Francisco and her people.

Condition Description

Very good condition. The detail is so clear that horses can be seen in mid-gait. Some surface abrasions. On nice, thick matte paper. Some acid toning on verso from old framing shows through to front.

Newspaper fragments recovered when we unframed the map suggest it was framed and displayed just weeks after the earthquake.

References