San Francisco Before Gold: the town of Yerba Buena as it appeared in March 1847, shortly after its capture by the U.S.S. Portsmouth.

View of San Francisco, Formerly Yerba Buena, In 1846-7 Before the Discovery of Gold

Out of stock

Description

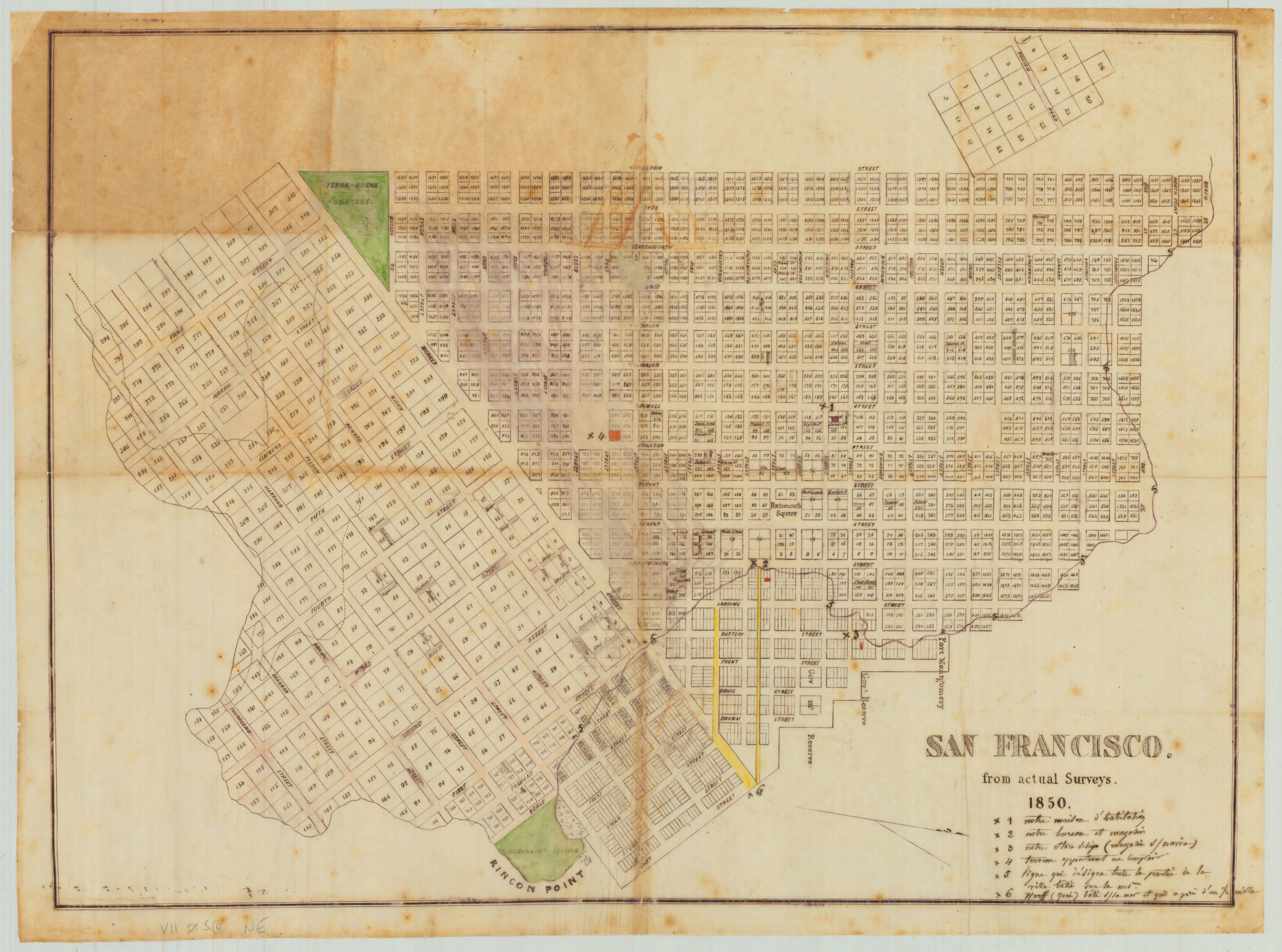

This superb chromolithograph depicts Yerba Buena/San Francisco in 1847, roughly a year before California formally became part of America and the Gold Rush started a massive immigration boom. Even though it shows San Francisco before the influx of tens of thousands of new citizens, the view was compiled and published in 1884. It was published by the prominent Bosqui Engraving and Printing Company and based firmly on the original drawings and depictions of Captain W.F. Swasey, who had settled there almost forty years earlier.

The view essentially provides an elegant overview of the small town of Yerba Buena, shortly after it had been taken from Mexico by Commander John B. Montgomery of the U.S.S. Portsmouth. At this time, there was little to indicate that a bustling city would replace this sleepy frontier town only a few years later. The perspective is a traditional bird’s-eye-view, which looks west from the Bay and across the peninsula. The town is centered around four main thoroughfares, all clearly indicated on the view. Running north-south, and thus parallel to our perspective, we find Kearney Street in the middle of town and Montgomery Street along the waterfront. The latter appears more like a walkway along the shore than a street. However, even today, Montgomery Street constitutes the original delineation of the coastline before redeveloping San Francisco’s waterfront. Intersecting these two streets at perpendicular angles are Clay Street and Washington Street. Together, these four streets form the heart of the city’s Financial District. The specific block formed by these streets and depicted in this view is the same today as occupied by the San Francisco Hilton and fronted by the iconic triangular skyscraper: the Transamerica Pyramid.

This view would have been virtually unrecognizable to most San Franciscans when published in the 1880s. We find letters, numbers, and other markers like arrows identifying concrete buildings, landmarks, or notable features to aid the viewer. These are linked to an extensive legend below the image. Among the identified places, we find early commercial structures such as William Leidesdorff’s warehouse (9) and City Hotel (5) or the Howard & Mellus Store (8), which the legend notes used to belong to the Hudson Bay Company. More public buildings like the Custom’s House (1), the Alcalde’s Office (4), or Yerba Buena’s first School House (3) are also noted. And then there are the residences of the pioneering families that made Yerba Buena their home. Among these, we see the Leidesdorff Cottage (11) or the residences of the Brannan (10) or Russ Families (12), among many others.

Immediately beyond Kearney Street is a large building with the American flag flying overhead: the so-called Calaboose or prison. Despite its seemingly imposing size, stories from the era tell of a flimsy structure where detainees would simply lift the doors off the hinges and roam about freely. On one occasion, a prisoner even headed up to the Alcalde’s office to demand that his breakfast be served! Once the Gold Rush saw men move in great numbers, a better solution was necessary, leading to the conversion of an abandoned ship to become San Francisco’s first real prison.

The legend does not only identify buildings, however. A series of ships lying at anchor in the Bay have also been lettered and named in the legend, allowing us to identify them firmly. The larger ships all belong to the U.S. Navy, with the biggest being the U.S.S. Portsmouth (A), which had seized Yerba Buena for the United States, and the slightly smaller craft to its right (B) being the troop transports that brought the New York 1st Regiment to be stationed here. The merchant ship Vandalia (C), consigned to Howard & Mellus, is seen to the far left of the scene, and beyond this, we see the small coastal schooner (D) that was among the most popular local craft.

Two arrows indicate important pathways away from the village. Beyond Washington Street, a path leads northwest out of town, past the residence of Francsico Cacarez (25). The legend identifies this as the pathway leading up to the military compound of the Presidio. On the other side of town, leading south from Clay Street is a similar path that leads down to the Old Mission Building. This structure was established by Father Francisco Pelou in 1776 and was, in effect, the oldest building in San Francisco. A few natural landmarks have also been noted on the view, including the peaks of Los Pechos de la Choco (33) and Lone Mountain (34), which respectively constitute today’s Twin Peaks neighborhood and the campus of the University of San Francisco.

Even though the information on the lithograph clearly attributes the composition to Captain W.F. Swasey, it was perhaps not him who compiled this final version of the image. Swasey’s sketches and drawings were nevertheless credible sources. He had settled in Yerba Buena as early as 1845 and was thus a long-time resident who had witnessed the changes personally.

The view was printed by the renowned San Francisco lithography firm Bosqui & Co., founded by Canadian immigrant Edward Bosqui in 1863, and is generally recognized as among the best lithography companies in San Francisco at the time. Bosqui issued two states of this retrospective color lithograph. While only the second was provided with an absolute date (1884), the two states were apparently issued just a year apart and showed only minute changes, indicating that it was a popular product that played on the nostalgia present in every rapidly developing society.

Two concrete features distinguish the two states: the expansion of the thick black copyright line at the bottom of the image itself. In the first state, this only notes the word COPYRIGHTED (e.g. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4364s.pm000332/?r=-0.232,0.202,1.75,0.828,0), whereas in our example it reads: COPYRIGHTED 1884 by W.F. SWASEY. Below this, in the white space of the title and legend, the words “C.P. HEININGER, Assignee” have been added, confirming that our example is a second-state issue. While there are no exact numbers for the print run of each state, and they are highly similar in appearance, the second state is generally considered the rarer of the two.

Context is Everything

The discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevadas in early 1848 drew so many hopefuls to California that over the course of just a few years, the sleepy town of Yerba Buena, with its roughly 300 inhabitants, was converted into the most prominent American metropolis on the West Coast and the most important Pacific port belonging to the United States. From when gold was first discovered at Sutter’s Mill in January until the following New Year, San Francisco grew with about 40,000 inhabitants. During 1849 – an iconic year in California’s immigration history – around 4,000 new settlers arrived in San Francisco every month.

Yerba Buena was originally a small town that had grown out of the nearby Mission. While the area was contested, it was officially a part of Mexico until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded it to the United States in 1848. The Mexican-American War started in May of 1846 when President James Polk called for the capture of California from Mexico. In July of that year, the U.S.S. Portsmouth, under the command of John B. Montgomery, sailed into the Bay of San Francisco and annexed the town of Yerba Buena without firing a single shot. While initially an illegal annexation, once the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, California officially came under the auspices of the United States.

Cartographer(s):

Edward Bosqui (1832–1917) was a Canadian artist and engraver born in Montreal. In 1850, he emigrated to California, eventually settling in San Francisco, where he became a well-known patron of the arts.

Little is known about Bosqui’s early life and training, but in 1863 he founded the Bosqui Engraving and Printing Company in San Francisco. Being a boom town, his firm did well in the beginning, living off the ample advertising opportunities that San Francisco and California presented. During this period of commercial success, Bosqui also dedicated himself to promoting culture – in particular, the arts. He was, among other things, a founding member of the San Francisco Art Association, which later would become the San Francisco Art Institute and which still exists today as the city’s Museum of Modern Art.

Bosqui’s success was not to last, though. In 1893, during one of the great conflagrations in early San Francisco (probably the Thomas Dye Works fire on August 9th), the Bosqui Engraving and Printing Company burnt to the ground. Four years later, another fire within the city destroyed his home.

Condition Description

Good. Previous repairs. Margins worn.

References