Frederick de Wit’s large folio of the British Isles in old color.

Nova totius Angliae, Scotiae et Hiberniae

$450

1 in stock

Description

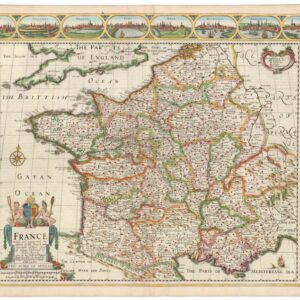

This scarce map of the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland is a splendid example of the systematic and highly aesthetic approach of 17th-century Dutch cartography.

The map is elegant and tightly executed, depicting one of the world’s hubs of political and military power at the time. While it was Frederick de Wit who compiled the map, it was published as part of an atlas issued by Nicholas Visscher in Amsterdam around 1680 and titled: Atlas Minor sive Geographia Compendiosa, qua Orbis Terrarum, per Paucas Attamen Novissimas Tabulas Ostenditur. Amstelaedami, ex Officina Nicolai Visscher.

The subdivision of the British Isles into its three constituent kingdoms is underlined by the original coloring, which leaves England yellow, Scotland pink, and Ireland green. The same three entities are also represented by their official coats of arms in the upper left corner, juxtaposing the elaborate and decorative title cartouche typical of the era. The cartouche is surrounded by putti and flanked on both sides by what appears to be water nymphs or sprites, as they sport both dragonfly wings and a fish-tail.

Within each kingdom, administrative subdivisions, such as counties, are also delineated using the same color scheme. While England is flanked by the North Sea, along the right fringe of the map, we find continental Europe represented by the Low Countries of Belgium and Holland. Within the North Sea, a small compass rose straddles an intersection of longitude and latitude delineations. Like most of his Dutch colleagues, Frederick de Wit applied the Mercator projection to many of his maps, including this one. This innovative way of projecting a three-dimensional sphere on a two-dimensional plane had first been proposed by Gerhard Mercator in 1569 but had by the 17th century become the dominant way of mapping large – especially maritime – expanses.

The technique stretches out space proportionally to its proximity to a pole to compensate for the Earth’s curvature when shown on a map. While this meant that both the northernmost and southernmost landmasses became more and more warped the closer one came to the poles, it also dramatically facilitated the correct navigation across open bodies of water in an age when doing so was of crucial importance to an aspiring empire.

Cartographer(s):

Frederick de Wit (1629–1706) was a Dutch cartographer and artist who drew, printed, and sold maps from his studio in Amsterdam. He was a pioneer of Dutch Golden Age cartography, and the founder of one of the most famous map-publishing houses in Amsterdam. He was born in Gouda but moved to Amsterdam at the end of the Thirty-Years-War (1618-48), which had engulfed most of Europe and ultimately liberated the Netherlands from centuries of Spanish dominion.

Soon after arriving in Amsterdam, probably in 1654, De Wit opened a printing shop named The Three Crabs (De Drie Crabben). A year or two before, he had married Maria van der Way, the daughter of a wealthy Catholic merchant, and this may have helped secure the funding to start his new operation. His aspirations as a cartographer were nevertheless made clear when he shortly after changed the name to The White Chart (Het Witte Pascaert), under which he gained international renown.

In the latter half of the century, De Wit began drawing, copying, and publishing atlases and maps. By the 1670s he was issuing large folios with up to a hundred maps in each tome, including a famous nautical atlas in 1675. From 1689, De Wit received a state privilege from the Dutch government to draw and issue maps. This protected his work from the illegal copying known from his earlier charts. De Wit was among the first to apply extensive coloring and his original color atlases and continental charts remain highly sought after to this day.

Following De Wit’s death in 1706, his wife ran the business for four years before selling it at auction in 1710. Their only surviving son was a successful merchant in his own right and had no interest in taking over. At the 1710 auction, most of De Wit’s plates were sold to Pieter Mortier, another Amsterdam cartographer and engraver. After passing the firm to his son, who teamed up with Johannes Covens, the firm became Covens & Mortier, the largest cartographic publisher of the eighteenth century.

Condition Description

Various repairs and infill, and other blemishes. Nice old color.

References