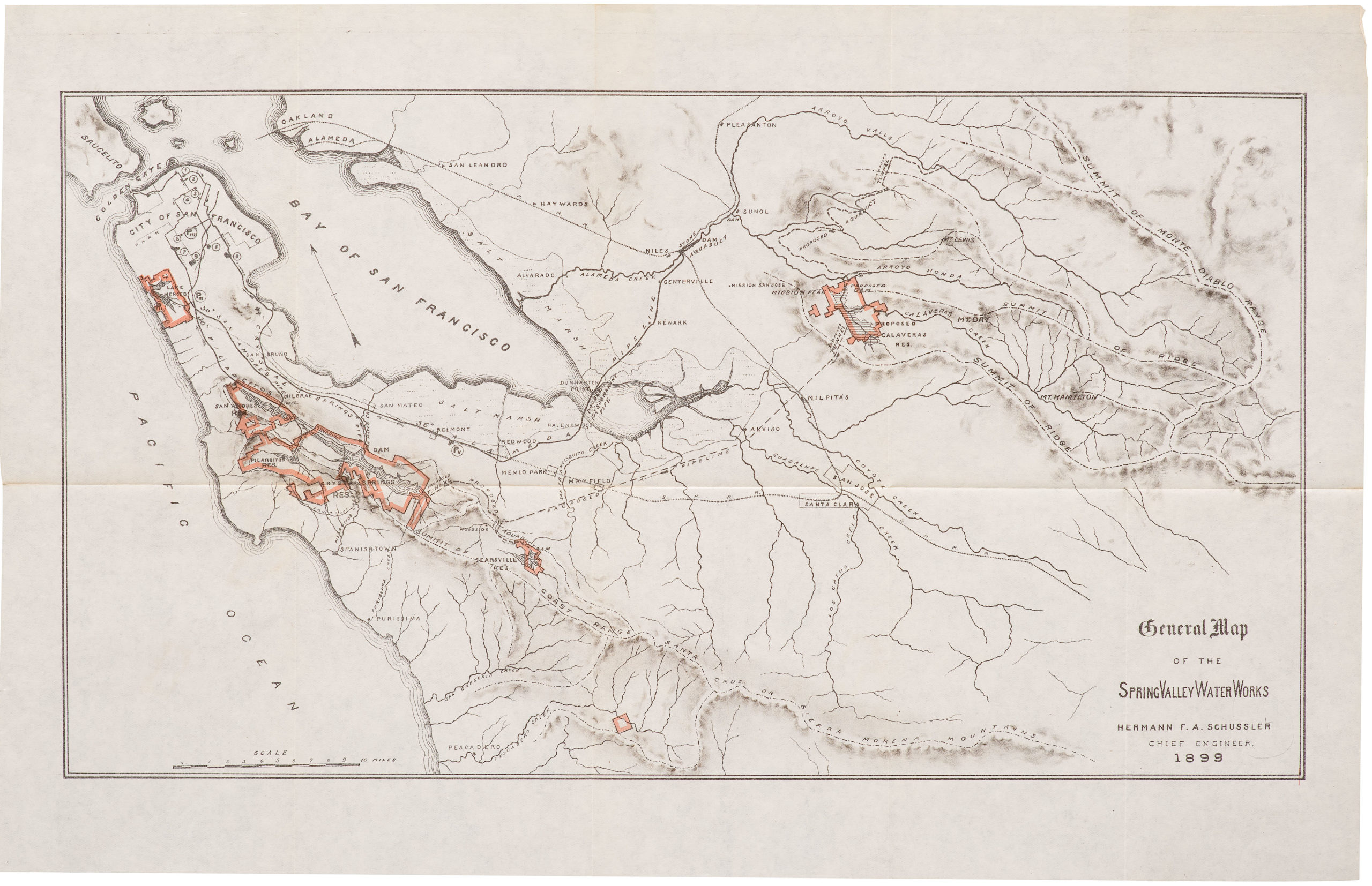

1853 United States Coast Survey steel-engraved master sheet map of the San Francisco Peninsula.

U.S. Coast Survey A.D. Bache, Superintendent, City Of San Francisco And Its Vicinity California. From a Trigonometrical Survey by R.D. Cutts, Assistant…

$2,500

1 in stock

Description

Listen to a short introduction to this map:

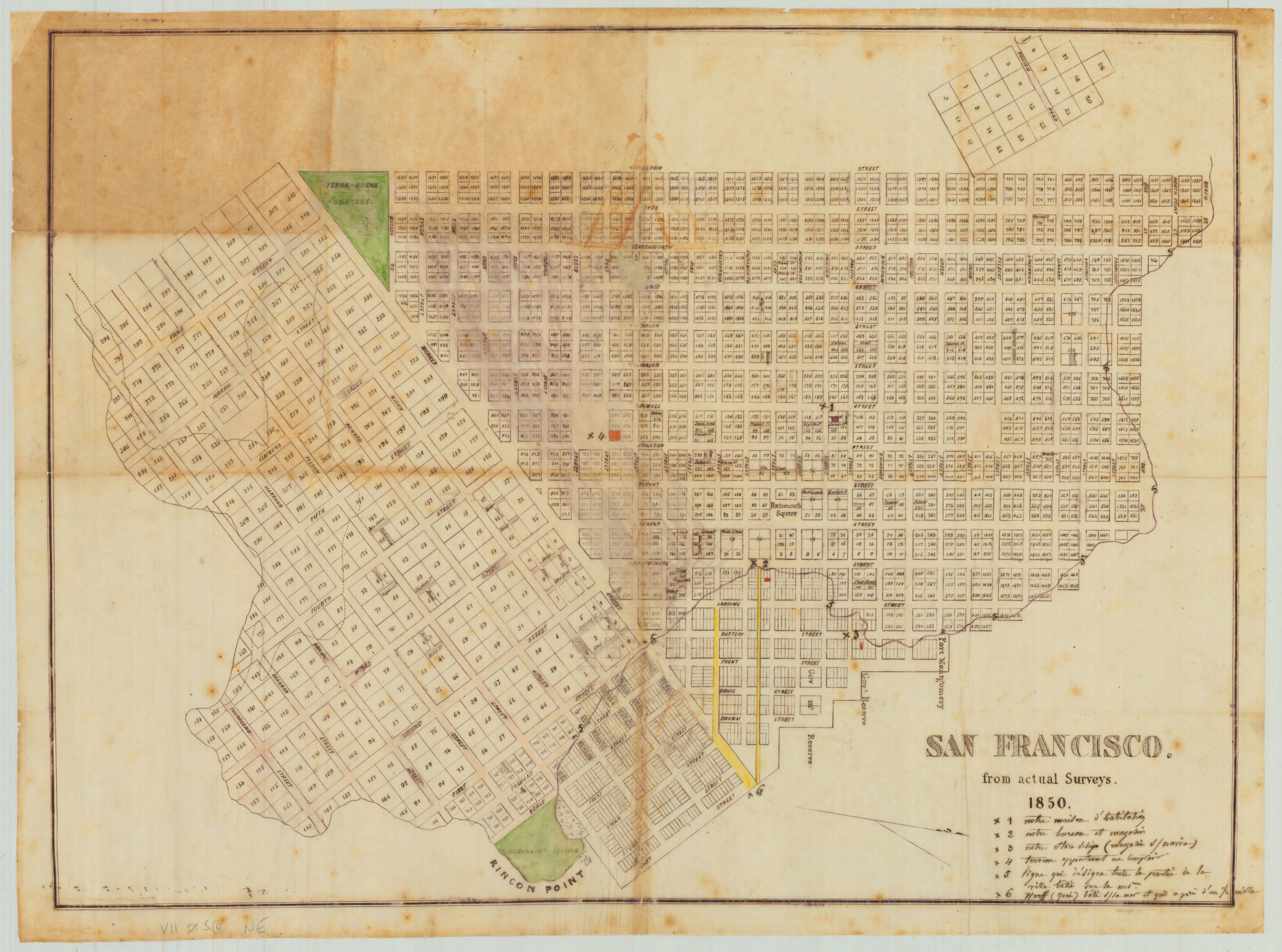

This is among our favorite maps because, perhaps more than any other, it accurately depicts the Gold Rush-era settlement on the San Francisco Peninsula. It is a product of the ambitious, large-scale mapping program known as the United States Coast Survey, which was created to accurately map the shifting borders and unknown lands of the ever-expanding American empire.

This early plan covers the northeastern corner of the San Francisco Peninsula, representing the city as it was in 1853. This included today’s downtown financial district, North Beach, the recently surveyed district south of Market Street, and the community clustered around Mission Dolores. It was derived from several sources, including Eddy’s official city map, with topography by A.F. Rodgers. The streets are laid out and named with detail down to individual buildings and contour lines at 20 ft. intervals showing elevation.

In the years before the publication of this map, San Francisco was a true boomtown, having grown from a sleepy village into a sizable city in about one year. In 1847, a year after the U.S. conquest of California, the pueblo of Yerba Buena was officially renamed ‘San Francisco’ by the newly appointed Alcalde Lt. Washington A. Bartlett. The following year, California was formally incorporated into the United States with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the cessation of the Mexican-American War. This set the stage for the greatest Gold Rush in history and the dramatic transformation of San Francisco into a bustling metropolis. In the summer and fall of 1848, after the discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills, the town of about 1,000 was nearly depopulated as its residents ran for the hills in search of gold. Two years later, after the 1849 Gold Rush brought gold seekers from all over the world, it had grown to a city of over 25,000—the largest on the Pacific coast of the Americas.

A vital aspect of the urban growth of San Francisco was its expansion eastward into Yerba Buena Cove. The in-filling of the cove was made possible by massive sand dunes, which were relocated into the Bay, and the sale of the resulting water lots generated much-needed revenue for the city. The city effectively consumed its natural environment to create new flat land. Indeed, this dynamic story is told by the map, which depicts the original shoreline around Montgomery Street — in this way, we see that a considerable portion of the heart of today’s downtown, from the Ferry Building north to Clark’s point, is built on land that was created ex novo in just a few years before the creation of this plan.

This map is also fascinating because it depicts areas that haven’t yet been developed. Beyond the western edge of the urban street grid at Taylor St., we see the contour lines of Russian and Nob Hills, followed by the bucolic plain of today’s Cow Hollow and Marina District. Exiting from about Mason and Broadway, we see the old Presidio road, a path connecting the original military garrison at the Presidio to the original maritime settlement of Yerba Buena. It follows a path likely used by Native Americans for millennia, as it is here that there is a slight dip between the heights of Russian and Nob Hill (even today, the best bike route over this area follows Pacific Ave). The Presidio road travels northwest towards the upper left corner of the map into an area known as Spring Valley. Partially extending out of the mapped area is Washerwoman’s Bay, a freshwater lagoon located around today’s Lombard, Filbert, Gough, and Octavia Streets. This became the site of a lucrative laundry industry until it became over-used and polluted, leading to several cases of cholera. The lagoon no longer exists because it was filled in by prisoners from the local jail in 1877; its memory survives in the name of Laguna St.

The original civilian settlement (as opposed to the military encampment at the Presidio) was the religious community at the Mission San Francisco de Asís, popularly known as Mission Dolores after a nearby creek named Arroyo de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores, meaning “Our Lady of Sorrows Creek.” As our map shows in dramatic detail, the center of gravity has shifted 2.6 miles northeast to Yerba Buena Cove at what could then be described as the distinct settlement of San Francisco, but a Plank Road connects the two. Plank roads were built by driving long tree trunks (usually redwoods from Marin County) deep into marshland, one after another, to create a passable walkway. They were often paid toll roads. The Mission Plank Road, as the name suggests, followed the line of today’s Mission St. It was built in 1850 with private funding.

The Mission itself is shown to be a small community dominated by the church, with an exhibition ring that featured such spectacles as duels and bull vs. bear fights located opposite. The natural landscape is still recognizable — indeed, this is one of the last maps before this area becomes drastically altered — with marshlands and small creeks extending well into today’s Mission neighborhood. The preferred alternative to travel from downtown San Francisco to the Mission was by boat, south around Steamboat Point (near the Giants baseball stadium today), into Mission Bay, and up Mission Creek to various docks in the marshes. From there, it was a short walk up what would become today’s 16th Street.

This example is a scarce master sheet, which was steel-engraved and probably for maritime or academic use. The paper is long-strand to accommodate the intaglio engraving. Such steel plates were used to create the lithographic impression for replicating and reducing the map into derivative lithographs and other printings. As such, it is very rare to find these on the market.

A note for the David Rumsey Map Collection listing states: “Vogdes shows this as the first edition. Vogdes says that the survey was completed in April, 1852, and that the interior topography was taken from Eddy’s official map of the city…In the Annual Report of the Survey for 1853, another issue of the chart was published (litho) with the addition of more notes regarding tides in the upper left – this same chart was also issued (engraved on thin paper) in the collection of charts published by the survey in 1854.”

Cartographer(s):

The Office of Coast Survey is the official chartmaker of the United States. Set up in 1807, it is one of the U.S. government’s oldest scientific organizations. In 1878 it was given the name of Coast and Geodetic Survey (C&GS). In 1970 it became part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The agency was established in 1807 when President Thomas Jefferson signed the document entitled “An act to provide for surveying the coasts of the United States.” While the bill’s objective was specific—to produce nautical charts—it reflected larger issues of concern to the new nation: national boundaries, commerce, and defense.

Alexander Dallas Bache, great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin, was the second Coast Survey superintendent. Bache was a physicist, scientist, and surveyor who established the first magnetic observatory and served as the first president of the National Academy of Sciences. Under Bache, Coast Survey quickly applied its resources to the Union cause during the Civil War. In addition to setting up additional lithographic presses to produce the thousands of charts required by the Navy and other vessels, Bache made a critical decision to send Coast Survey parties to work with blockading squadrons and armies in the field, producing hundreds of maps and charts.

In 1871, Congress officially expanded the Coast Survey’s responsibilities to include geodetic surveys in the interior of the country, and one of its first major projects in the interior was to survey the 39th Parallel across the entire country. Between 1874 and 1877, the Coast Survey employed the naturalist and author John Muir as a guide and artist during the survey of the 39th Parallel in the Great Basin of Nevada and Utah. To reflect its acquisition of the mission of surveying the U.S. interior and the growing role of geodesy in its operations, the U.S. Coast Survey was renamed the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey (USC&GS) in 1878.

Condition Description

Very good. Thick paper. Strong impression with platemark evident.

References