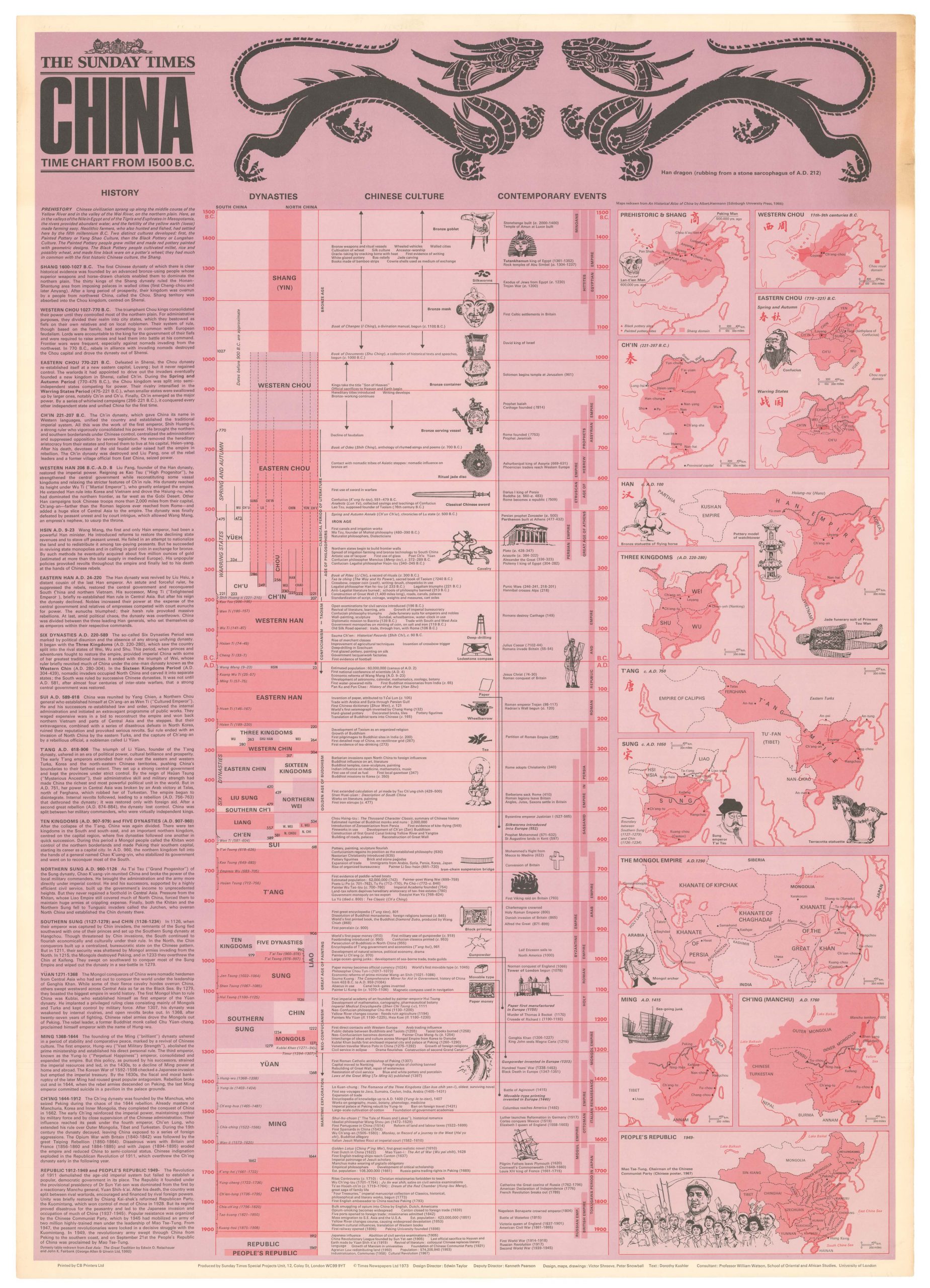

The Japanese capital on the verge of modernity.

安政改正 府鄉御江戶繪圖 / [Sketch Map of the City and Villages of Edo, Ansei Revised Edition].

Out of stock

Description

Neatline is excited to present this large and detailed map of Edo, the capital of the Tokugawa Shogunate in early modern Japan. Like most Japanese maps from the Edo period (1603-1867), this chart was produced as a woodblock print. The maker was Takashiba San’yū, although it seems that he had some help in compiling it (more on this below). Typical of Japanese cartography at the time, the map is dated by period, not by year, which means the exact publication date is difficult to establish.

What we can say, however, is that the map belongs to the Ansei period, which lasted from November 1854 through March 1860. This is the exact same period that Japan, which at this stage had been isolated from the rest of the world for centuries, was forcibly opened to the world by the Americans. The consequences were rapid and profound social, economic, and cultural changes that rattled even the most progressive Japanese citizens.

The subject of this map is the Tokugawa capital at Edo, which soon would be renamed Tokyo. It depicts a sprawling urban center on the eve of dramatic upheaval. The swiftness with which everything changed would unsettle Japanese society and eventually lead to the downfall of the Tokugawa Family in 1868. But it would also usher in a period of intense modernization and cultural experimentation known as the Meiji Restoration.

The map is oriented west at the top and with the famous Chiyoda Castle (御城) at the heart of the map. This flatland castle was originally built in 1457 by Ota Dokan but was converted into the Imperial Palace and the seat of the Military Government by the legendary founder of the dynasty, Tokugawa Ieyasu. The palace can be easily identified on the map as the urban nucleus and the only place within the city not characterized by a dense sprawl of buildings and narrow streets. This was the residence of the Shogun and his immediate family, whereas the extended family and other elites (daimyo and samurai) lived in large dwellings close to the Castle.

As is evident from our map, it was the residences of this elite class, along with temples and shrines, that occupied the vast majority of the urban space in mid-19th century Edo. Many of the elite residences have been shaded green on our map and in some instances even provided with tiny drawn-in trees to underline the tranquility and beauty of these urban estates. The large population of commoners (shomin, 庶⺠), on the other hand, lived in tightly packed gated-off neighborhoods (machi 町) and small villages on the outskirts of the city, some of which are included on the map.

The map is detailed and notably dense with information. There are countless labels – many in red cartouches – which identify everything from Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples to streets, bridges, and the individual blocks of specific neighborhoods. At the bottom left of the map, we find a tabled legend in Japanese, which lists the distance of various neighborhoods from Nihonbashi (日本橋). Nihonbashi is a commercial district located immediately east of Chiyoda Castle (i.e. below it on the map). It grew up around the canal bridge of the same name, which had linked the two sides of the Nihonbashi River since the early 17th century. In addition to being the city’s marketplace, Nihonbashi was also the terminus of the Tōkaidō Road, which was the most important of the five official routes that connected Edo with the old cultural capital at Kyoto. Along with the Kyobashi and Kanda areas, this constituted the Shitamachi, or the original downtown center of Edo.

Complex compilation

This map was officially compiled by Takashiba San’yū (高柴三雄) and published by Suharaya Mohē (須原屋茂兵衞). However, several other Tokyo-based cartographers and publishers also appear to have contributed to its creation, including Yamashiroya Sahē (山城屋佐兵衞), Kobayashi Shinbē (小林新兵衞), Izumoji Manjirō (出雲寺萬次郎), Yamazakiya Seishichi (山崎屋清七), Okadaya Kashichi (岡田屋嘉七), Yamashiroya Heisuke (山城屋平助), and Tsutaya Kichizō (蔦屋吉藏). Our map bears a strong resemblance to a contemporary chart titled 萬世御江戶繪圖 by Yorozuya Shōsuke (萬屋庄助), Fujiya Kichizō (藤屋吉藏), and Yamashiroya Masakichi (山城屋政吉). Still, given the multiple editions and vague dating, the exact printing order is unknown.

Context is Everything

During the tumultuous 16th century, Japan underwent a process of unification that was strongly influenced by its long preceding history of civil war and social instability. During this period of strife, Japan had been open to the world, enjoying trade not only with its Asian neighbors but also with the Portuguese out of Goa and later with the Dutch as well. After the Tokugawa clan ousted competition and took over control of the entire country, concerns about the impact of foreign ideas (especially Christianity) and foreign goods (especially firearms) on the newfound stability of the Shogunate caused the ruler to initiate an isolationist policy known as Sakoku (鎖国, literally “chained country”). This saw Japan closed off to the outside world on pain of death. Some external influences continued to seep into Japan, primarily through the mercantile hub of Nagasaki, where Dutch and Chinese traders were still allowed to reside and trade.

During the 19th century, foreign ships began landing on Japanese shores with increasing frequency, but the isolationist policy was maintained. It was only with the arrival of a US Navy fleet under Commodore Matthew Perry in July of 1853 that Japan was forced to open itself to the outside world again. The ubiquitous and comprehensive changes that ensued would eventually bring down the Tokugawa Shogunate and initiate the Meiji Restoration.

Sakoku Cartography

Despite the isolationism of the Edo period, some Japanese intellectuals did have a superficial awareness of the outside world, as well as of the advances in cartography that the 19th century had seen. Working with limited materials and under strict censorship, Edo cartographers were still able to produce relatively accurate maps of Japan and East Asia using a combination of local surveying techniques, Chinese maps, and older European maps. While the exact date of this map is difficult to determine, it is clear that it was compiled at a time when foreign influences were first being felt among Japan’s intelligentsia. With the end of isolationism, the established market for Edo-period maps exploded due to growing public interest.

Census

The OCLC catalogs examples of this map in the institutional collections of the University of California Berkeley (4 distinct holdings) and Yale University (no. 61744825). Similarly, examples are found in various Japanese archives, including the National Museum of Japanese History.

The map is extremely scarce on the market.

Cartographer(s):

Okadaya Kashichi or 岡田屋嘉七 (c.1658-1874) was a prominent Tokyo-based publishing house that produced a wide variety of publications, including maps.

Suharaya MohēSuharaya Mohē or 須原屋茂兵衞 (c.1684-1904) was a prominent publishing house and bookseller in the Edo and Meiji periods. The firm was known for publishing works related to the city of Edo (modern Tokyo), including some of the best maps of the imperial compound.

Takashiba San'yūTakashiba San’yū or 高柴三雄 (c.1848-1879) was a Sokuku cartographer who primarily made maps of his hometown Edo. He is also known for an updated and more accurate map of Japan from the late 1840s (大日本国郡輿地全図).

Condition Description

Very good. Original fold lines visible. Some wear along margins.

References

![[Pair of views] Rade et Ville de Sincapour & Rade de Sincapour prise de la maison du Gouverneur](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NL-00896-harbor_Thumbnail-300x300.jpg)

![[Pair of views] Rade et Ville de Sincapour & Rade de Sincapour prise de la maison du Gouverneur](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NL-00896-harbor_Thumbnail.jpg)

![[Cook’s Discovery of Eastern Australia] Carte de la Nle. Galles Merid. ou de la Cote Oriental de la Nle. Hollande.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/NL-01183_Thumbnail-300x300.jpg)

![[Cook’s Discovery of Eastern Australia] Carte de la Nle. Galles Merid. ou de la Cote Oriental de la Nle. Hollande.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/NL-01183_Thumbnail.jpg)