A spectacularly gilded first edition of Moreau’s allegory on the True Faith.

Typus Religionis. Estampe, du tableau trouvé dans l’eglise, des ci-devant soi-disans-Jésuites de Billom en Auvergne, l’an 1762.

Out of stock

Description

A superb engraving full of history and symbolism, the source of which is included under The Art of Blasphemy in scholar Edward Brooke-Hitching’s The Madman’s Gallery: The Strangest Paintings, Sculptures and Other Curiosities from the History of Art.

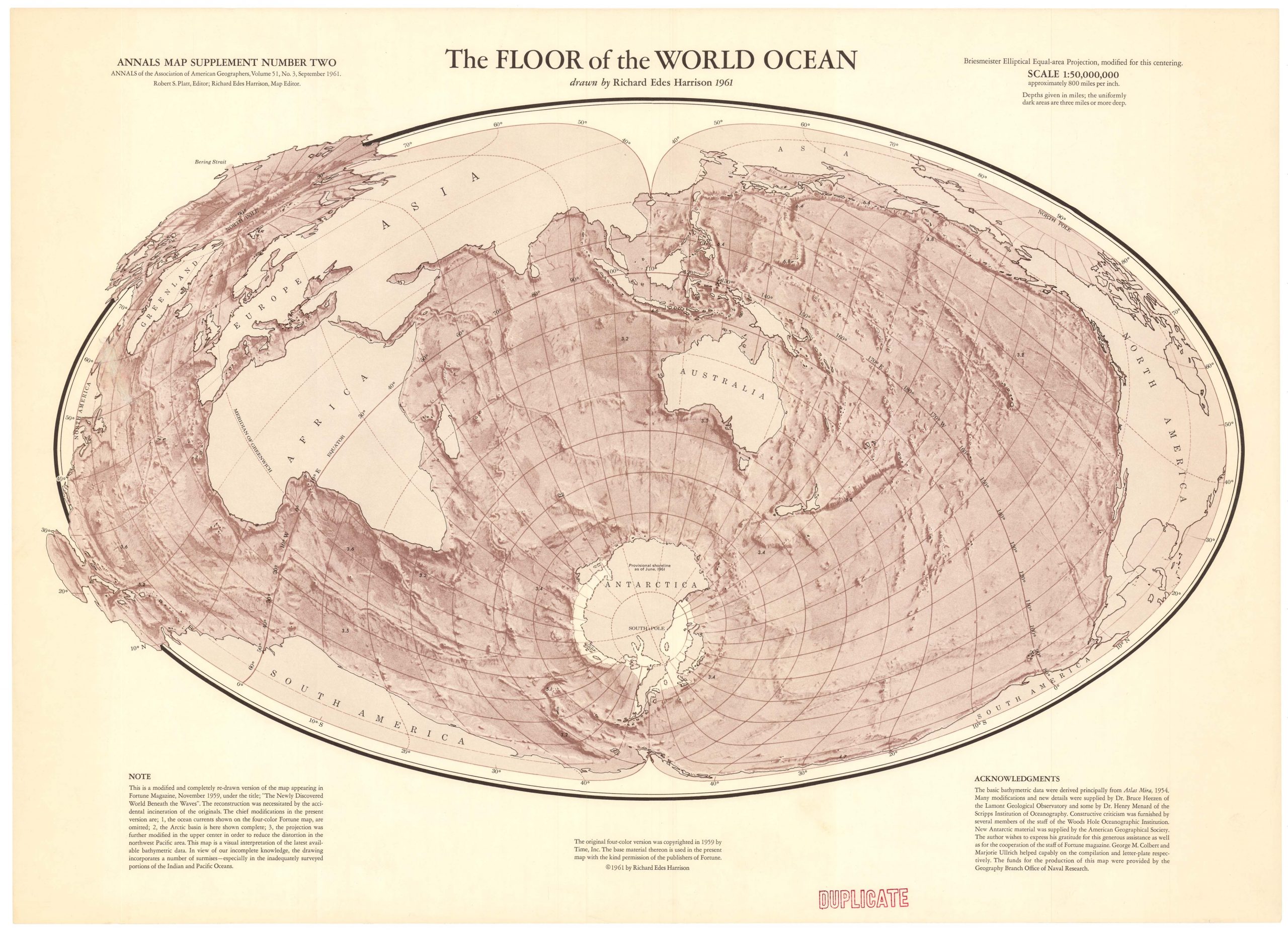

This highly decorative and large-format engraving is of considerable historical significance. It constitutes a reduced version of a famous late sixteenth or early seventeenth century (ca. 1700) oil painting, which today is housed at the Musée de l’Histoire de France in the Hotel de Soubise in Paris. The original painting once adorned the Jesuit Billom College in Auvergne, but it was ripped down and confiscated when the King of France persecuted many of the Catholic orders in 1762. The painting was offered as evidence of the Jesuit denigration of Catholicism and the Crown and played a crucial role in the fall of the Society of Jesus in France (Brooke-Hitching, p. 141).

The engraving is superbly colored in bright reds, blues, yellows, and greens and generously highlighted with gold leaf. Much like the original painting, an enormous ten by twenty feet canvas, the engraving is impressive, measuring 82.5 by 44.5 cm (32.5 by 17.5 in), including margins.

The astounding composition is essentially an allegory of Salvation through Christ. It consists of a large central galleon – the ship of the True Faith – brimming with clergymen on all decks and with the Jesuits firmly in charge. While the craft is a metaphor for Catholicism, its destination would have been very real to many people in the 17th and 18th centuries. Departing a fundamentally sinful world of the flesh, this great vessel of Christ is heading towards the Kingdom of God – seen here as a golden city on the left side of the image. Flanking the Port of Salvation sits Death on a podium.

Immediately below the main mast and seemingly in command of the vessel, we find St. Ignatius de Loyola (1491-1556), co-founder of the Jesuit Order. Hovering above his outstretched hand is a glowing Christogram of the Society’s official seal while he firmly grasps the Holy Book in his other hand. Standing in a long row behind him are several influential Church Fathers, including St. Francis of Assisi (Order of the Friars Minor), St. Bruno (Order of Carthusians), St. Dominic (Order of Preachers); St. Basil (Eastern monasticism), and St. Anthony (Western monasticism). The inclusion of these specific characters is not random but rather a visual framing of Ignatius – and thus the Jesuits – as the culmination of great Church fathers. Immediately behind this impressive lineup, the helmsman and navigator are keenly focused on the task at hand.

The image was produced at a time when allegory and symbolism were the mainstays of political critique. The eternal threat of humankind’s sinfulness is represented as vessels on the prowl in the distant upper right corner of the image. Each is labeled as one of the seven deadly sins, and all of their flanks are dominated by golden shields to underscore their violent intent and capabilities.

The waters around the galleon are brimming with enemies of the Faith, which become physical threats to the faithful desperately trying to escape. In the lower-left corner of the image, we see how one of the smaller vessels is filled with demonic figures with grotesquely deranged faces. These representations of evil are tugging at a large, bountiful fishing net cast from the galleon. The fish symbolize the meek and faithful, here seen rescued by the Jesuits. Moving left to right along the bottom panel of figures, we find apostates struggling in the water next to the boat of demons. Several of these are finely dressed, probably because they represent the nobility that opted to support the French Crown. One is in the unfortunate situation of being swallowed whole by a rather dog-like sea monster or whale.

Squeezed between the lower panel of boats and the more distant ‘deadly sin’ vessels, we find a small craft labeled Naves Seculariom, representing secular power. Its passengers include King Henri IV of France with crown and scepter, and the Pope, lost in the pages of a large book. The vessel tries to latch onto the larger craft but is repelled by a shield on which is written ‘Doctrina Sana’ (Right Doctrine). Presumably, the artist was trying to convey that while the King may publicly strive to rekindle relationships with the Church, his apostasy is recognized by those of True Faith.

Context is Everything

Even though they wielded immense political, social, and economic power throughout most of Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Catholic Orders gradually became too autonomous, too obstinate, too violent, and too arrogant for local rulers to keep accepting their presence and power. The Portuguese crown was the first to expel the Jesuits in 1759. France followed suit and made them illegal in 1764, and Spain and Sicily began taking repressive actions from 1767 forward. Opponents of the Society of Jesus achieved their greatest success when they took their case to Rome. By 1800, the power and influence of the Catholic Orders – in particular the Jesuits – had been dramatically reduced.

Census

The painting behind this print is undated. The engraving was made later to accompany a notice on the fate of the College of Billom, which was published in the Recueil de plusieurs des ouvrages de Monsieur le President Rolland in 1783. A second state, with all the texts translated into French, was produced in 1826 for La galère Jesuitique.

Our example of this historic engraving is the first state from 1783. This edition can be found in a small number of institutional collections in Europe, including the Bibliothèque national de France (OCLC no. 693492896) and The British Museum (museum no. 1998,1004.27). In the United States, the OCLC lists examples at the Newberry Library in Chicago, Loyola University Library (no. 187317250), and the Getty Research Library (no. 801825552).

Cartographer(s):

Jean Michel Moreau, a.k.a. Moreau le Jeune (1741-1814), was a French draughtsman, illustrator, and engraver. The son of a Paris wig-maker, Moreau was attuned to fashion and style from an early age. In 1758, he apprenticed as a painter and followed his master to St Petersburg. The experience left him wanting, and Moreau returned to Paris the following year, completely abandoning painting in favor of engraving. He soon proved to be a skilled draughtsman and was given prestigious commissions such as Diderot’s Encyclopédie or the novels of writers such as Voltaire or Rousseau.

In 1770, Moreau was named Designer to the King of France, and in 1781 promoted to Engraver to the King. During the bloody years of the French Revolution, he managed to survive and prosper as an engraver and illustrator. In 1814, Louis XVIII re-appointed him to a royal office, but Moreau died shortly after.

Condition Description

Excellent condition, with later color with lavish gold highlights.

References

Brooke-Hitching, Edward. The Madman's Gallery: The Strangest Paintings, Sculptures and Other Curiosities from the History of Art. Chronicle Books, 2023.

![[Set of Four Allegorical Mezzotints of the Continents] America. Europa. Africa. Asia.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/NL-01491-asia_thumbnail-scaled-300x300.jpg)

![[Set of Four Allegorical Mezzotints of the Continents] America. Europa. Africa. Asia.](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/NL-01491-asia_thumbnail-scaled.jpg)