Braun & Hogenberg’s extraordinary rendition of Elizabethan London as Shakespeare knew it.

Londinum Feracissimi Angliae Regni Metropolis.

$8,500

In stock

Description

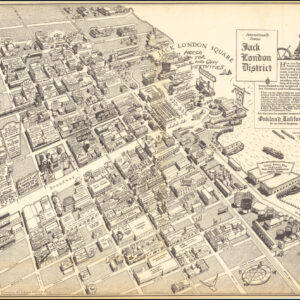

This gorgeous bird’s-eye-view is among the earliest obtainable depictions of London. It captures the English capital during one of its most dynamic and exciting historical periods. Compiled for, and printed in, the first volume of Braun and Hogenberg’s iconic city atlas, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, this particular view has become highly sought-after due to the detailed and time-specific rendition of Elizabethan London, especially because the Great Fire of 1666 changed the face of the medieval city forever.

Braun and Hogenberg’s view was likely based on a much larger wall map, compiled sometime between 1547 and 1559 and consisting of no less than twenty conjoining sheets. Known as the ‘Copperplate Map,’ this was most likely the earliest printed map of London, but sadly no examples of this groundbreaking cartographic endeavor have survived. In the 1990s, however, three original plates were identified, making it clear that Braun and Hogenberg’s rendition shares many crucial details with this important predecessor.

Among the striking parallels are the application of an oblique aerial view and the inclusion of key landmarks, such as the tall spire of St Paul’s Cathedral. The plate including this celebrated spire, was among those discovered in the 1990s, and the likeness with B&H’s depiction is indubitable. The inclusion of the spire indeed was an adaptation from the Copperplate Map is evident not only from the striking similarity in depiction but also by the fact that the spire was struck by lightning in 1561 and subsequently caught fire and collapsed. This event happened more than a decade before Braun & Hogenberg’s view was published and would have been an inclusion that hinged more on nostalgia and recognisability than contemporary cartographic accuracy.

In addition to St Paul’s Cathedral, we note several vital features that characterize Elizabethan London and constitute essential landmarks in the English capital today. On the right side of the view, bordering the north banks of the Thames, we find ‘The Tower,’ London’s oldest and most secure royal castle. For more than 500 years, English monarchs used this luxurious fortified complex to guard the royal family and its possessions in times of war and rebellion. Nevertheless, the enormous complex also served other key functions, such as housing the Royal Mint and safeguarding prisoners deemed a threat to the realm. Among those imprisoned and executed at the Tower were enemies of the state (e.g. Guy Fawkes and Thomas More) and rival nobility and royalty (e.g. the Scottish royals). Mistresses and royal consorts like Anne Boleyn and Lady Jane Grey were also imprisoned and executed here.

At the opposite end of the view, after the river has turned south, we find the equally famous borough of Westminister, built around the Abbey of the same name. This Gothic cathedral is perhaps the most famous in the UK and is consistently used for the realm’s highest ceremonies, such as royal weddings, coronations, and burials. The Abbey began as a Benedictine monastery almost a thousand years ago but had, in Elizabethan times, become the most important church in the country. Most importantly, Westminister constituted the royal residence during times of peace, standing in contrast to the Tower complex at the other end of the city. Beyond it lay the royal hunting grounds of St James Park, here depicted with stags and all. Perhaps one of Westminister’s most interesting features is the inclusion of the royal tennis courts.

More than simply being an early depiction of London, Braun and Hogenberg’s view is important because it documents how rapidly the Tudor city was being transformed during the mid-16th century. For one thing, it is clear that Tudor London had grown well beyond the city walls, which had defined the urban limits since the time of Alfred the Great. Extending west from the heart of the city, we find extensive gardens, manor houses, and palaces sprawled along the bank of the river in the direction of Charing Cross, and from there, along The Strand, to Westminster. These wealthy residences soon linked the mercantile center with the royal court at Westminster. Across the Thames, Southwark is also depicted as increasingly urbanized. It retains some features generally associated with the city’s outskirts, such as the bull and bear baiting rings, a hugely popular form of public entertainment during the Elizabethan era. This area would soon be transformed into a new theatre district, with Shakespeare’s Globe being erected in 1598.

The river is teeming with life, underscoring how London’s success as a trade center hinged on its riverine placement. Ships and boats of all varieties zig-zag its waters. Some of these are larger transport vessels, while others are smaller barges designed for crossing the Thames at various locations. In the middle of the image, we find the famous London Bridge spanning the Thames.

At the bottom of the image, four figures overlook the city, a common feature in Hogenberg’s engravings. In this case, depicting them as merchant couples underlines London’s status as a mercantile hub with a vibrant economy. Flanking either side of the figures are panels of text. The left provides a brief history of the city, whereas the right panel discusses the so-called steel yards, a remnant of the Hanseatic presence in London that ran from the 11th to the late 16th century. While the Hansa had played a crucial role in building up London’s mercantile and defensive capabilities, they came to be viewed as foreigners and were increasingly marginalized during the Elizabethan era. Queen Elizabeth finally expelled the Hansa from London in 1597.

Census

The view was originally published in Braun and Hogenberg’s famous city atlas: the Civitates Orbis Terrarum. This tome was an enormous endeavor and forever changed the nature of mapmaking and urban cartography.

Neatline’s example of this map is the second state, dating to 1574, which can be identified by the “cum privilegio” added to the top of the lower right cartouche and the alteration of Westmester to Westmu(n)ster.

Because this view was included in every edition of the first volume of Braun & Hogenberg’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum, a considerable number of institutional examples exist (OCLC nos. 433712775; 1197919624; 313164461). Single sheets of the view are also recorded, but only in the National Libraries of France and Spain (OCLC no. 1225129877). Because it is the earliest comprehensive view of one of the world’s greatest cities, it continues to command high prices in the open market.

Cartographer(s):

Georg Braun (1541 – 10 March 1622) was a topo-geographer. From 1572 to 1617 he edited the Civitates orbis terrarum, which contains 546 prospects, bird’s-eye views and maps of cities from all around the world. He was the principal editor of the work, he acquired the tables, hired the artists, and wrote the texts.

The main engraver for volumes I-IV was Frans Hogenberg (1535–1590), a Flemish and German painter, engraver, and mapmaker.

Condition Description

Old color, expertly refreshed. Minor repairs to chipping along the edges.

References

![[Pair of views] Rade et Ville de Sincapour & Rade de Sincapour prise de la maison du Gouverneur](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NL-00896-harbor_Thumbnail-300x300.jpg)

![The Original Silicon Valley Map & Calendar [1994]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/NL-00909_Thumbnail-300x300.jpg)