Rare St. Louis-printed map of antebellum Missouri, meant to inspire a new wave of emigration and settlement.

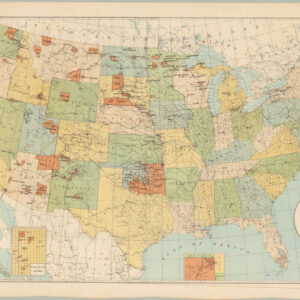

Clark’s New Sectional Map of Missouri compiled & engraved from the United States land surveys and other reliable sources. St. Louis: J.C. Clark & Co., 1860

Out of stock

Description

Published just before the American Civil War, this is one of the rarest and most impressive mid-19th century documents pertaining to the development of the “Show Me State.” It was published locally in St. Louis, and constitutes an important cartographic record of antebellum Missouri; a region that following the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and the Missouri Compromise (1820) became America’s official ‘Gateway to the West.’

The map was issued at a time when Missouri had been part of the Union in one form or another for more than half a century. During the course of these fifty-some years, massive settlement had taken place across the sea of grass to the west beyond the Mississippi River. This trend continued throughout the 1840s and 50s, underscoring just how pivotal Missouri had become for all those seeking a new life and prosperity in the West, as well as anyone seeking to profit from these hopes and dreams.

It is consequently of no great surprise, and entirely in line with the deep-rooted American spirit of entrepreneurship, that this unique and extremely detailed map of the state should have been commissioned by real estate agents rather than by the government.

A work of the highest quality

The map is one of the most comprehensive and elaborate maps of Missouri following the extensive settling that occurred in the wake of statehood (1821). It measures an impressive 29 by 33 inches (73.5 x 85 cm) and was originally issued for commercial purposes by the St. Louis-based real estate agents J.C. Clark & Co. It was drawn and lithographed by Julius Hutawa, also of St. Louis. Indeed, this emergent metropolis played a crucial role, not only in the map’s composition, but on the state’s historical development.

Hutawa printed the map as a lithograph on two separate sheets, which were subsequently joined and hand-colored. The coloring frames the map both visually and thematically, in that allows each of the individual counties to be clearly distinguished. Moreover, it depicts every town of significance within the state, as well as roads, railroads (both extant lines and planned ones), steamboat navigation points, postal offices, and county churches. The survey work of the General Land Office is clearly identifiable in the map’s organizational grid layout.

Two other interesting features plotted by the mapmakers are active mills and iron banks. The former speaks to the nature and goal of this map: it was meant to appeal to those seeking a homestead. It was the intention of Clark & Co. to instill in the viewer a sense that one could actually live here. For that purpose, domestic infrastructure such as congregational venues and mills to process home-grown yields were central elements when conjuring up images of a new life in the minds of its viewers. For their part, the iron banks, which belonged to J.C. Clark himself, speak to the possible economic opportunities offered by the land here.

Another element prominently included in the legend on Clark & Co.’s map are Missouri’s United States Land Offices. These were charged with overseeing the allocation of available land and verifying ownership once claimed or bought. Five Land Offices are listed: at St. Louis, Boonville, Warsaw, Springfield, and Jackson. The distribution of the offices would seem to relate to the five irregularly-shaped land districts demarcated on the map by thick red hachure lines. In any event, the Land Offices are just another example of the attention to detail offered to contemporary purchasers of this map. To this point, there is a clue on the inside of the map’s covers, namely a Cincinnati book seller’s advertisement. We can thus allow ourselves to imagine that this particular map was purchased in Cincinnati by an intrepid traveler set to make his or her way to the west.

In the open space west of the depicted landmass, we find a legend specifying a number of elements on the map. At the top are the explanations of symbols and specific line types, each of which denote a concrete function. Below these, we find an interesting list of so-called ‘Chartered’ (i.e. proposed) railroad lines planned for the coming years. These would of course increase connectivity within the state and thus facilitate everything from personal travel to the ability to acquire goods and building materials by mail order. Below this, we find the addresses of the state’s five Land Offices, the importance of which we have already stressed.

Census

This map is rare and rarely offered for sale. The OCLC lists only five institutional copies, held at the University of Michigan Clements Library, the State Historical Society of Missouri, the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, the British Library, and the Kansas City Public Library.

Context is everything

The great expanse known as the Missouri Territory was initially included in the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase (1803), in which President Thomas Jefferson bought an enormous swathe of land from Napoleon, on behalf of the United States. Settlement in the former colonies had by then pushed as far west as possible within the extant land constraints, and the Louisiana Purchase opened up an entirely new world of possibilities for the ambitious or dedicated emigrant. For almost a century, Missouri, and St. Louis in particular, were known as the ‘Gateway to the West’ – a role encapsulated in the monumental Gateway Arch that since the 1960s has been St. Louis’ primary landmark. Many of the iconic journeys west, be they of expedition or exodus, started from here; St. Louis was, for example, both the beginning and end point of the great Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806). Our map draws heavily on this idea of a bustling gateway, which of course manifested itself in a plethora of physical and political infrastructure, cementing Missouri as the ideal staging point for any westward journey.

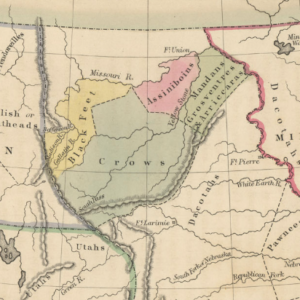

While Missouri had been part of the Louisiana Purchase, it was only admitted as a formal part of the Union when the Missouri Territory applied for admission as a Slave State in the 1819 legislature known as the Missouri Compromise. From 1821, it was formally acknowledged as a state and the speed with which this occurred is a direct reflection of the area’s importance vis-a-vis a continued push west. Initially, Missouri’s western and northern borders were delineated at a right angle. This delineation hinged on the Kawsmouth, or the point where the Kansas River flowed into the Missouri. This point set the state’s western border, also known as the Osage Line. However, in 1836 additional land was usurped from Native American tribes to the northwest through a forced buy-out known as ‘The Platte Purchase.’ This saw the already enormous territory significantly expanded to the northwest, making the Missouri River itself the new borderline. This map captures this expansion mid-process and is thus highly representative of Missouri’s historical formation.

Among the many people emigrating into this new area of the United States from an early stage were farmers and plantation owners from the south, who brought with them the scourge of slavery. During the 1830s, more emigrants settled on the Missouri frontier, many of them Mormons coming from the east or north. Conflict soon arose between the ‘old’ settlers and the new arrivals leading to the Mormon War of 1838. By the following year, most of the Mormons had been evicted from the state and their lands had been confiscated. Rather than returning east or north where they came from, this prompted a new Mormon drive further west. In this way, Missouri history is one of the key drivers behind the eventual creation of Mormon lands in Utah.

Missouri’s central geographical placement in America and its role as the ‘Gateway to the West’ meant that this region saw significant development, and conflict, in the latter half of the 19th century. Despite being a slave state, Missouri never actually ceded from Union during the Civil War, but being a border state in more than one sense, it did see deep internal divisions and numerous violent confrontations. It nevertheless also meant that Missouri’s greatest city, St. Louis, was the fourth largest in the United States at the dawn of the 20th century. Its pivotal role as the hub of the Midwest meant that in addition to rapid demographic growth, it hosted grand national events such as the 1904 World Fair (also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition) and Olympics.

Cartographer(s):

J.C. Clark & Co. was a 19th century real estate agency based in St. Louis.

Julius HutawaJulius Hutawa was among the early German immigrants to Saint Louis, arriving with the Berling Society in 1833 along with his brother Edward. The brothers were soon engaged in lithography and publishing, and among the maps created by Julius Hutawa are Frémont and Nicollet’s Map of the City of St. Louis (1846), Map and Profile Sections Showing Railroads of the United States (1849), Map of the United States Showing the Principal Steamboat Routes and Projected Railroads Connecting with St. Louis (1854). They also published city views.

Condition Description

Expertly flattened and backed for preservation. Includes original green cloth covers, the upper cover lettered in gilt; advertisement for map publisher E. Mendenhall of Cincinnati pasted to front pastedown. Wear visible along old fold lines and where previously attached to covers.

References