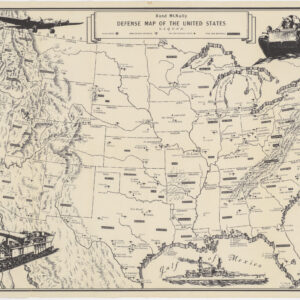

A map of American potential; a map that points towards a great, but still unfulfilled future.

Map of the United States of America, the British provinces, Mexico, the West Indies and Central America with part of New Granada and Venezuela

Out of stock

Description

Key points:

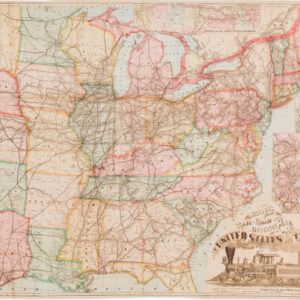

1. This large and imposing chart of the United States, issued by the renowned firm of Joseph H. Colton in 1850, is in many ways the primordial map of the American West.

2. The map manifests crucial themes like westward migration and the early territorial development of the Trans-Mississippi, and highlights the emergence of infrastructure and connectivity.

3. It was published at a momentous and dynamic time in American history, as reflected for example in the colossal geographical configurations of Texas and California.

Colton’s 1850 triumph captures the formative days of America, in which the United States had almost reached its current geographic outline, but where the internal configuration was ephemeral and still very much in its infancy. The map postdates the incorporation of vast Mexican territories into the Union following the cessation of the Mexican-US War (1846-48) and the ensuing Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, but it predates the creation of the first smaller territories, such as Utah, Washington, Idaho, and Kansas, which essentially took place in the years after this map came out. Consequently, we are presented with an American West in which California, Oregon, Texas, and Greater Nebraska were still enormous untamed frontiers.

Publication history and context

Colton published three distinct maps of the United States in 1850: a standard 1-sheet pocket-map, a 4-sheet wall-map, and then this very rare intermediate version, which consists of a two-sheet edition. The intermediate version was itself available in multiple versions, including as sheets (sometimes dissected and laid on linen) and as a folding-map (offered here). The three maps provided one of the most up-to-date and comprehensive views of the United States at the time, especially of the the western half of the country, including the large areas annexed after the Mexican-American War in 1848. The updated editions also tried to anticipate and preempt the the outcome of the Compromise of 1850. This set of five bills passed by Congress in September sought to defuse the growing tensions between slave-owning and free states in the new territories that had been incorporated into the U.S. following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which Mexico ceded more than half of its territory to the United States (including parts of present-day Arizona, California, New Mexico, Colorado, Nevada and Utah). The updated editions also included the most recent findings of John C Frémont, as well as the huge discoveries of gold made at Sutter’s Mill in California, which set in motion the famous 1849 Gold-Rush.

The template was widely used for the next decade, although the annual editions saw many amendments and changes, reflecting the dynamism of the epoch. Some of these have become seminal in their own right, such as the important 1854 editions, which gradually document the formalization of Nebraska and Kansas as US Territories: https://neatlinemaps.wpengine.com/antiquemap/nl-00919/coltons-1854-map-of-the-united-states-of-america

Essentially we see a united country in which the great Mississippi Valley forms a palpable dividing line between the highly developed East and the wild frontiers of the West. It is an exceptionally beautiful map of considerable historic importance. The map’s coverage extends from Canada in the north to Colombia (New Granada) and Venezuela in the south. It includes all of the United States, Mexico, Central America, and the West Indies. The entire map is surrounded by a decorative border consisting of slender stylized columns wrapped in grape-vines and interspersed with inset pictorial scenes from the American continent. While the map originally was compiled by Colton himself, and this border was designed and engraved by William S. Barnard, the engraving of the map itself was done by John M. Atwood, who captured an emergent nation in fascinating detail.

Part of what makes this particular Colton map so attractive among collectors are indeed the two artists involved in its execution. Atwood especially stood out, and this map is typical of his elaborate and ornamental style. In fact, collectors and map scholars have proposed that he probably oversaw Barnard’s work on the border as well. Barnard’s artistic contribution is nevertheless also among the features that elevates this map from its peers.

In its entirety, the map includes a total of thirteen pictorial scenes (as well as fifteen vessels inserted into the maritime sphere). Of these, twelve are incorporated into Barnard’s border, while the thirteenth consists of a dramatic scene showing a bald eagle perched on a star-spangled banner-shield and clutching the symbols of peace (olive branch) and war (arrows) in its talons. Any school child in the U.S. would immediately grasp this as a national symbol, but in 1850, following a massive expansion of the country and its citizenship, this unifying symbolism was more pertinent than ever. With its keen sight, the eagle constituted an embodiment of the all-seeing eye and the victory of freedom over tyranny. Surrounding the main scene we find all the trappings of an independent America: navigational tools, trade goods, and agricultural bounty — all set within the landscape of a well-developed bay.

Returning to Barnard’s pictorial scenes, we find a larger vignette in each corner, and two smaller scenes along each fringe. Clockwise from top right, the four corner vignettes illustrate the valley of the Connecticut River as seen from Mount Holyoke (and with a hunter firing his rifle from the shrubs); the still incomplete Capitol Building in Washington D.C.; the Great Cathedral of Mexico City, revealing a continued US interest in Mexico; and finally, salmon fishing at Willamette Falls in Oregon. The smaller vignettes at the top and bottom of the map illustrate John Jacob Astor’s fur trading outpost in Oregon, Lake Saratoga in New York, Mexicans engaged in catching wild steer, and ships entering an unidentified port. Along the right and left flank of the map we find illustrations of the Pulaski Monument in Savanna, the Battle Monument in Baltimore, the Bunker Hill Monument in Boston, and a mysterious ‘Washington Monument’ in New York City — an unbuilt commemorative monument meant for Hamilton Square on the upper east side of New York City.

We see an America divided by habitation, infrastructure, and development. With some important exceptions, the dividing line was basically the Missouri and Mississippi River Valleys. But America was a land of growth. It was in its DNA, and no river or frontier was to halt American progress. Thus we see that the lands on either side of the river were efficiently incorporated and developed in the early decades of the 19th century. Frontier States such as Iowa (statehood in 1846), Missouri (1821), Arkansas (1836), and Louisiana (1812), were all integral parts of the Nation. Beyond them lay the great unknown, full of dangers, but equally full of potential. This atmosphere, of an America that at least internally was still very much taking shape, has completely saturated the map. It is iconic precisely because it on one hand shows the great idea that is America, but on the other hand reveals the reality of this idea to remain undefined and amorphous.

Colossal Lone Star and Golden States

The most blatant example of the primordiality of America’s configuration in 1850 is perhaps Texas, which at this stage still includes two-thirds of New Mexico, as well as the Oklahoma Panhandle (although the labelling of the rest of Oklahoma as Indian Territory is new when compared to the 1849 original). The inclusion of New Mexico as a distinct territory reflects just how up-to-date Colton’s maps were, as this was only formalized that same year. The southern border of Texas and New Mexico is still somewhat fluid at this stage, and would only become firmly established with the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. In the north of Texas, on the other hand, a degree of clarity has been accomplished as to where the border of Texas was to be drawn. This had been an issue for some time and in the 1849 edition parts of southwestern Nebraska were hatched to show possible affiliation with Texas. But this issue was one of many resolved in the Compromise of 1850, and here we see Colton affirming the validity of this agreement by drawing a very clear border around Texas.

Moving out of Texas and New Mexico, one is immediately struck by the enormous size of California, which includes all of what would later become Nevada (1864) and Arizona (1912). Similarly gigantic is the Territory of Oregon, which virtually encompasses the entire Northwest Pacific. While Oregon would not attain statehood until 1859, California reached this important milestone the same year this map was issued, as part of the Compromise of 1850. Despite this fact, and despite the fact that other elements of the Compromise have been incorporated on the map, there is little to suggest that such progress was underway. California is, in fact, represented using the same terminology that was applied in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, namely as Upper or New California (in an attempt to distinguish it from its Mexican counterpart).

A lot had happened in the few years between the end of the Mexican-American War and the publication of this map. Consolidating the Mexican territories under an American aegis was a messy and somewhat rushed process, which is why maps from this period are often cutting-edge in some ways, but antiquated in other ways. California’s formal incorporation into the Union was of course a major development and in part spurred by the 1849 Gold-Rush, which saw mass emigration to California from both the East Coast and the Old World. Colton knew how important it was to tap into this inflated demand for reliable and accurate maps. Indeed, part of the reason for amending and reissuing the 1849 map was to include the most recent information as it pertained to gold. Consequently, while even the 1849 edition included references and demarcations such as ‘Eldorado’ or ‘Gold Region’ in California, from 1850 we also find the routes of John C. Frémont’s expeditions in eastern California, where especially his exploration of the Humboldt River was of interest to prospectors.

Another interesting feature of California is found in its northeastern corner, in what today is Utah. Here, at the culmination point of Frémont’s easternmost ventures, we find the Great Salt Lake clearly delineated in the landscape. By 1850, the area is already clearly recognized as being dominated by the Mormons. But when the initial Mormon settlers arrived here in 1847, this was still Mexican territory. It was only with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that it came under the aegis of the United States, and only with the Compromise of 1850 that it was separated from California and declared its own Territory. Along the eastern banks of the lake we see a bold black label claiming the area as a Mormon Settlement, and on the southeastern shore we find the original Mormon fort that would soon develop into Salt Lake City. This original fortification, which was fondly known as ‘Plymouth Rock of the West’, expanded so rapidly between 1847 and 1849 that by the time this map was published, it was already something of an anachronism. The settlement had simply outgrown the constraints of the original fort and its inclusion on this map thus constitutes a unique window into the brief foundational years of Salt Lake City, and even Utah itself. For while Utah remains formally unrecognized on this map (other than as a tribal denomination), its formalization into a U.S. Territory was happening at the same time that this map was issued. The decisive changes following from the Compromise of 1850 would soon be recognized cartographically as well, and by the time Colton issued his next big national map in 1854, the American West looked and felt completely different.

Greater Nebraska

This paucity of certain territorial toponyms on the map brings us to the fourth and final quadrant of the West, namely the unorganized terrain of Greater Nebraska. This enormous territory encompasses the endless plains between the Missouri River and the Rockies, as well as the many Native cultures that it sustained. This was a time before the Transcontinental railroad had connected America’s coasts and so anyone wanting to make it out west would need to either arrive in California by ship (usually from the Central American isthmus) or traverse these immense lands. Most settlers would follow a network of overland routes known as the Oregon Trail. This cut from Ohio across Nebraska and the Rockies, to Oregon and California. Following the Gold-Rush, these trails saw a spike in traffic, which meant that soon after important details started appearing on Colton’s map. Among them are delineations of the Oregon Wagon Trail, including distance markers in miles along the route. The fact that these are the earliest days of the American Westward Migration is quite clear from the omission of other established trails, such as the southerly Santa Fe Route. Instead, we are provided with the route of General Kearney’s 1846 military expedition.

But things changed quickly in the 1850s and by the time Colton published his next new map of the Nation in 1854, the inclusion of multiple wagon trails and overland routes had become standard. The paucity of mapped trials at this stage, made it all the more important to depict the larger rivers in detail, as these served as the main fix points and traffic arteries for pioneer travelers. In addition to providing reliable direction, drinking water, and game, rivers were easy to identify and were often associated with a degree of infrastructure like trading outposts, forts, and other types of frontier settlements. Just as wagon trails, river valleys, and frontier forts are all neatly demarcated, so too are the regional divisions of Native American Tribes. Interaction with Native Americans was virtually impossible to avoid for settlers moving across the prairie, so knowing who was friendly and who was less so, was of critical import.

Insets and additional features

A final note should be made on the a number of features found at the bottom of the map. In addition to a table that provides the overland distances from eastern hubs to western hubs in miles, there are two inset maps, both of which are directly related to the migration of new people to the American West — in particular California. The largest, in the lower left corner of the map, constitutes a map showing the Atlantic Ocean and the various steamer routes crossing it. It is quite clear from this map that there were certain fixed routes of getting to and from the American West, especially if you were arriving from Europe. The inset map shows the standard steamer routes at the time, underlining that European travelers primarily would depart from either Liverpool in England or Bremen in Germany (with stops on the Isle of Wight as well).

An alternative route veered south to stop at Madeira, before crossing closer to the equator. In these cases, the destination was usually somewhere in the Caribbean, with off-shoots to Caracas. Like the larger map, this inset has been supplied with a small Table of Distances (in Africa) specifying the nautical distances between major ports. The oceanic space in this little map has — much the like the larger map — been adorned with several depictions of ships. These are a mix of sailing ships and steam driven carriers, such as the ones used when emigrating from European this time. This is in fact an interesting detail, for our map was published in the middle of the major transition from sail to steam in passenger ships. American vessels had dominated the crossing in the first half of the 19th century, but when steamships took over in the second half, British ship-building technology revealed itself as vastly superior to that of America. The new British steamers were larger, faster, and more reliable in bad weather, and their introduction revolutionized (and streamlined) trans-oceanic travel and opened up America to the world. They also very nearly destroyed the American carrier industry. Once again, our map captures this important transition in American history. Soon steam engines would be transporting passengers across the continent as well.

The last inset, just right of the Atlantic Crossing one, shows the Central American isthmus around Panama in great detail. Following first the incorporation of massive territories after the Mexican-American War and then especially the California Gold-Rush of 1849, many European emigrants were of course looking to settle in the American West. But they were perhaps not inclined to take the arduous and wild journey across land. Instead, the wealthier would travel directly to San Francisco, from where they would set up their various enterprises. This was of course a long time before the construction of the Panama Canal, but the narrow strip of land was already then recognized as the easiest place to cross from the Atlantic to the Pacific seaboard. For this reason, the authorities had begun constructing a railway stretch that was meant to carry passengers and goods across the isthmus, from Panama City to the Pacific port of Chagres, where people and property could be loaded unto new ships and sail north to California. Construction of this railway began in 1849 and so it has been tentatively included on Colton’s map. But the project was not completed until 1855, and is thus still under construction when this map was issued.

Cartographer(s):

The Colton Mapmaking Company was a prominent family firm of cartographic printers, who in the nineteenth century were leaders in the American map trade. Its founder, Joseph Hutchins Colton (1800-1893), was a Massachusetts native who in 1830 moved to New York City and slowly began setting up his publishing business, which in the beginning drew heavily on licensing maps by established engravers such as David H. Burr, Samuel Stiles & Company, and later Stiles, Sherman & Smith. Smith was a charter member of the American Geographical and Statistical Society, as was John Disturnell. This connection would later benefit Colton, in that it helped him to acquire the rights to several important maps.

By the 1840s, the Colton firm were producing their own maps. They produced anything the markets desired, from massive and impressive wall-maps to pockets guides, folding maps, immigrant guides, and atlases. One of the things that set the Colton company aside from many of its contemporaries in terms of quality, was the insistence that only steel plate engravings be used for Colton maps. These created much more well-defined print lines, allowing even minute features and labels to stand out clearly. By 1850, the Colton firm was one of the primary publishers of guidebooks, immigration itineraries, and railroad maps in America.

In the 1850s, Colton’s two sons, George Woolworth and Charles B., were brought on board to the firm. This inaugurated a process of expansion in which the company began taking international commissions and producing wholly independent maps and charts. From 1850 to the early 1890s, they also published several school atlases and pocket maps. The firm continued until the late 1890s, when it merged with a competitor and then ceased to trade under the name Colton.

Condition Description

Folding map with original covers. Discoloration along several folds. Minor loss at one fold intersection.

References

Cohen, Paul E. 2002 Mapping the West. America’s Westward Movement 1524-1890. Rizzoli: New York.

Hayes, Derek 2007 Historical Atlas of the United States. With Original Maps. University fo California Press: Oakland.