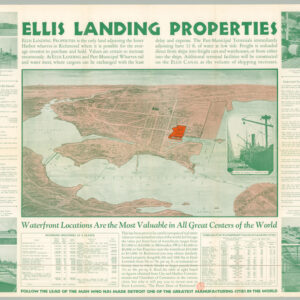

A rare and important 1860 Bay Area rancho map.

Map of the Country 40 Miles Around San Francisco, Exhibiting County Lines, and correct Plats of all the Ranchos finally surveyed and of the Public Land Sectionized. Compiled from United States Surveys by Leander Ransom

Out of stock

Description

Rare separately issued map of San Francisco and environs, published in San Francisco by Leander Ransom and lithographed by L. Nagel in San Francisco.

Leander Ransom was among the most important and influential mapmakers and surveyors in the early years of California, having conducted the foundational survey work for the U.S. Surveyor General and having served as the first clerk of the General Land Office’s San Francisco Office beginning in 1851.

The present map was produced by Ransom likely in part due to the demand for information on the location of ranchos in the Bay Area, at the height of the pre-Civil War Rancho Claims litigation. The present map would likely have been useful to lawyers, speculators and title companies as a small format overview of the tangled web of rancho claims and claimants in the decade following California Senator William M. Gwin’s “An Act to Ascertain and Settle Private Land Claims in the State of California,” was approved in 1851, which set off decades of litigation over the ownership of the vast majority of the settled and inhabited lands in California.

Unlike most other maps of the period, Ransom’s map is focused on the location of the Spanish and Mexican ranchos in the San Francisco Bay area, with the map locating and providing the details of dozens of ranchos. The rancho detail is quite fine, with the name of the rancho and its original grantor shown, as well as additional information for many ranchos, including the date of the grant and the number of acres.

The map also locates the borders of the then existing counties, including San Francisco County, Santa Cruz County, San Mateo County, Santa Clara County, Alameda County, Contra Costa County, Sonoma County, Napa County and Solano County.

Among the ranchos noted is Suscol Rancho in south Napa County and extending into Solano County. This Rancho would become the subject of one of the most important bits of litigation (and the subsequent Suscol Act) during the resolution of the title claims of the various Rancho owners after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

The history of the ranchos dates to Spanish rule in Upper California. Following Mexico’s independence, the land grant system continued, with many of the area owners taking their grants in the 1830s and 1840s.

Following the conclusion of the war with Mexico, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided that the Mexican land grants would be honored. In order to investigate and confirm titles in California, American officials acquired the provincial records of the Spanish and Mexican governments in Monterey.

In 1851, the United States Congress passed “An Act to Ascertain and Settle Private Land Claims in the State of California.” The Act required all holders of Spanish and Mexican land grants to present their titles for confirmation before the Board of California Land Commissioners. Contrary to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, this Act placed the burden of proof of title on landholders. In many cases, the land grants had been made without clearly defining the exact boundaries. Even in cases where the boundaries were more specific, many markers had been destroyed before accurate surveys could be made.

Aside from indefinite survey lines, the Land Commission had to determine whether the grantees had fulfilled the requirements of the Mexican colonization laws. While the Land Commission confirmed 604 of the 813 claims it reviewed, most decisions were appealed to US District Court and some to the Supreme Court. The confirmation process required lawyers, translators, and surveyors, and took an average of 17 years (including the interruption caused by the Civil War, 1861–1865) to resolve. It proved expensive for landholders to defend their titles through the court system. In many cases, they had to sell their land to pay for defense fees or gave attorneys land in lieu of payment.

Land from titles not confirmed became part of the public domain, and available for homesteaders, who could claim up to 160-acre plots in accordance with federal homestead law. Rejected land claims resulted in claimants, squatters, and settlers pressing Congress to change the rules. Under the Pre-emption Act of 1841, owners were able to “pre-empt” their portions of the grant, and acquire title for $1.25 an acre up to a maximum of 160 acres. Beginning with Rancho Suscol in 1863, special acts of Congress were passed that allowed certain claimants to pre-empt their land – without regard to acreage. By 1866 this privilege was extended to all owners of rejected claims.

The rancheros became land rich and cash poor, and the burden of attempting to defend their claims was often financially overwhelming. Grantees lost their lands as a result of mortgage default, payment of attorney fees, or payment of other personal debts. Land was also lost as a result of fraud. A sharp decline in cattle prices, the floods of 1861–1862, and droughts of 1863–1864, also forced many of the overextended rancheros to sell their properties to Americans. They often quickly subdivided the land and sold it to new settlers, who began farming individual plots.

The Ransom map is rare. OCLC locates two examples (Bancroft and UC Davis). The second example may be a photocopy.

Cartographer(s):

Leander Ransom was born on September 5, 1800, in Colchester Connecticut. He spent time in New York State, before moving to Ohio in 1825. Early in his career Ransom was employed by the Ohio Canal Company and in 1826 he was appointed to locate a portion of the Ohio Canal. Later he was appointed as Commissioner to the Ohio Canal Commission. In 1836 he was appointed as President of Board of Public Works of Ohio, a position he held for 13 Years.

Ransom first came to California in 1851 to work with Samuel D. King, who was the U. S. Surveyor General for California. King and Ransom left New York by steamer for California in May of 1851. They left their ship and crossed the Isthmus of Panama overland, then boarded another steamer and continued their trip to San Francisco. They landed in San Francisco on June 14, 1851, and set up offices there.

On July 8, 1851, King issued special instructions to Ransom for the establishment of the Initial Point on Mount Diablo and the initial surveys of the Meridian and Base Line. King charged Ransom to “Go to Mount Diablo and provide that: an east and west Base and north and south Meridian line be run and established passing through the most prominent peak of Mount Diablo.”

From July 1851 to September 1851, Ransom conducted the first Public Land Survey in California as Deputy Surveyor. The Mount Diablo Principal Meridian and Base Line extending from the Mount Diablo Initial Point, established on July 17, 1851 by Ransom, controls Public Land Surveys within two-thirds of California and all of Nevada. In August of 1852, King ordered Ransom to examine the southern California region of San Bernardino Mountains to see if it would be feasible to establish an initial point on its summit. Ransom reported to King that it would be possible. In September of 1852, King issued instructions to Henry Washington, Deputy Surveyor to establish the San Bernardino Initial Point.

After completing these tasks, Ransom would go on to serve as Chief Clerk in the California Surveyor General’s Office in San Francisco until the 1860s.

In 1853 Ransom became a Charter Member of the California Academy of Sciences. In addition, he was an early and active member of the Academy, serving as President for eleven terms beginning in 1856.

Condition Description

The map has been expertly cleaned, conserved and restored. A number of tears have been repaired and several large areas of facsimile added to the bottom right and left corners of the map, the top left corner and the area to the west of San Mateo, along with several lesser repairs along the neat lines. Margins extended.

References