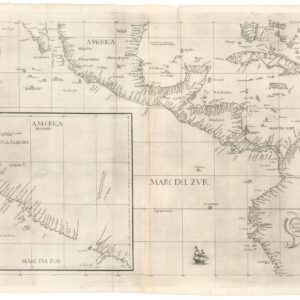

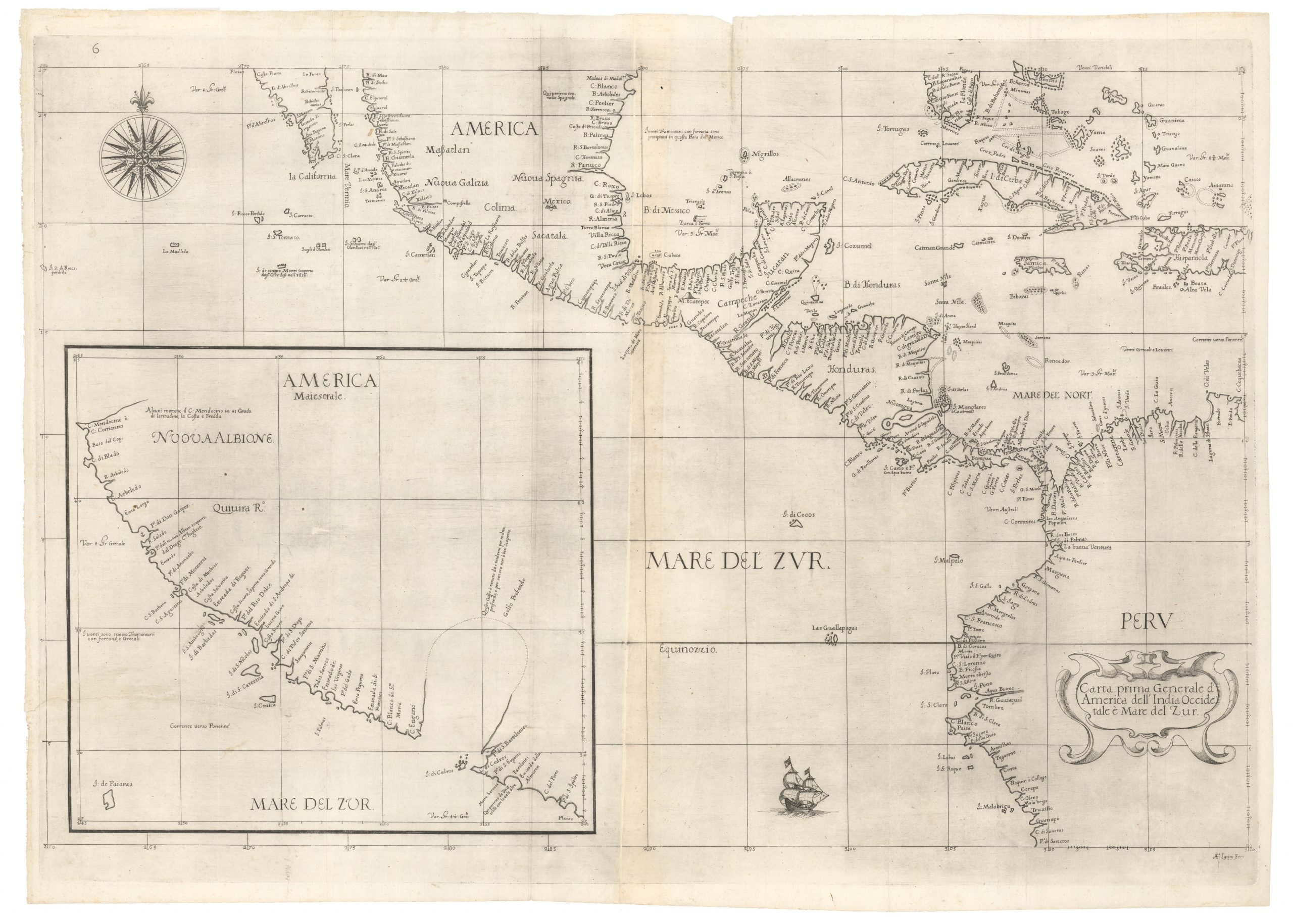

1541 map of the New World with references to Christopher Columbus, from the Admiral’s Map

[Title on Verso] Tabula Terra Novæ

Out of stock

Description

One of the earliest and most important maps available to collectors of American maps, this is Laurent Fries’s slightly reduced, and more decorative, version of Martin Waldseemüller’s landmark map covering the Atlantic coastline of the Americas, including the Florida peninsula and the Gulf Coast, and islands.

In 1513, Waldseemüller published an edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia that included a supplement of twenty modern maps. Two of these depicted the New World: a world map, and the forerunner of the example offered here, the first map devoted to the Americas to appear in an atlas. Waldseemüller is most famous for being the first cartographer to use name ‘America,’ a term which he placed on his 1507 world map; before this land was labeled ‘terra incognita.’ In doing so, he was giving discovery credit to Amerigo Vespucci – ‘Amerigo’ became ‘America’ in the tradition of continents taking a feminine gender. The only known copy of this map was bought from Germany by the United States in 1999 for $10 million.

For its part, Waldseemüller’s Atlantic map is often referred to as the Admiral’s Map because he attributed his source of information on the New World to ‘the Admiral’ – assumed to be a reference to Christopher Columbus. Waldseemüller attempted to distance himself from the credit he had given to Vespucci by specifically crediting Columbus with two lines of Latin text, which read: Hec terra cum adiacentib insulis inuenta est per Columbu ianuensem ex mandato Regis Castelle (this land with its adjacent islands was discovered by Columbus, sent by authority of the King of Castile). These lines are kept by Fries, next to which he has added graphic depictions of cannibals and a fierce-looking opossum, both of which had been reported by Amerigo Vespucci.

The geography of Fries’s map follows that of the 1513 Waldseemüller and delineates the Atlantic from latitudes 35° south to 55° north, with a surprisingly accurate depiction of the American coastline. In the Caribbean, the islands of Cuba, Hispaniola (Spgnoha), and Puerto Rico (Boriguem) are shown, along with numerous other islands. Fries added the Spanish flag flying over Cuba (named Isabella after the Queen of Spain) and a text block beneath Hispaniola that describes the island and Columbus’s discoveries in 1492. He renamed the new world Terra Nova and retained the two famous lines of Latin text from the 1513 edition.

The map shows a continuous coastline between North and South America, with the massive east-west coastline of South America being the map’s single largest feature, extending south to approximately the Rio de la Plata lies. North America is plotted to beyond the mouth of the St. Lawrence; at the correct latitude of the St. Lawrence there is a river named Caninor, quite possibly the St. Lawrence. This region had almost certainly been already explored by various Bristol expeditions. In all, over 15 place-names are shown on the North American Coastline, drawn primarily from Portuguese sources, including the Cantino Map of 1502 (for more on this map see: https://neatlinemaps.wpengine.com/blog/2017/2/10/the-cantino-planishpere-returns-to-ferrara).

The map also features two imaginary islands that are well-known to researchers of cartographic history. The first is Hy Brasil, a circular island split in the middle, which is most often found off the coast of Ireland. Hy Brasil is said to emerge either from a thick fog or from the ocean itself for only one day every seven years. A short distance to the south is another famous phantom island: Mayda (on this map called ‘Asmaidas’). Possibly born as a duplication of Hy Brazil, Mayda is one of the most enduring myths we see on antique maps, being depicted for over five centuries. This persistence despite a complete paucity of written evidence to support the existence of the island has long puzzled map scholars. Brooke-Hitching argues that the island may have in fact existed in the past, only to sink beneath the waves after a geologic event and points to observations by ships off the coast of southern Brittany corroborating this theory.

Burden identifies four different states of this map, as determined by the title on the reverse of the maps: TABVLA TER. NOVAE (Strasbourg 1522), Oceani occidëtalis Seu Terre Noue TABVLA (Strasbourg 1525), OCEANI OCCIDENTALIS SEV TERRAE NOVAE TABVLA (Lyon 1535), and the current example, Tabula terræ nouæ (Vienne 1541).

The book in which this map was published proved controversial; Jean Calvin ordered copies destroyed, and the publisher, Michael Servetus, was burned alive for heresy. As noted by Burden, the Lyon and Vienne editions weigh in on the debate over the use of the ‘America,’ with two lines of text at the end of the page on the verso: Toto itaque, quod ajunt, aberrant coelo qui hanc continentem Americam nincupari contendunt, cum Aericus multo post Columbum eandem terram adierit, nec cum Hispanis ille, sed cum Portugallensibus, ut suas merces commutaret, eo se contulit.

Cartographer(s):

Laurent/Lorenz Fries (ca. 1485-1532) was born in Alsace circa 1490 and studied medicine and mathematics at a number of European universities. He was trained as a physician but was also keenly interested in cartography and medical publications. From 1518-19 Fries is mainly based in Strasbourg, where he was commissioned to compile the first edition of Waldseemüller’s atlas after his death in 1520.

Martin WaldseemüllerMartin Waldseemüller (c. 1470 – 16 March 1520) was a German cartographer. He and Matthias Ringmann are credited with the first recorded usage of the word ‘America’ — on the 1507 map Universalis Cosmographia in honor of the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci.

Condition Description

Excellent impression on paper with a bunch of grapes watermark and minor show through of text on verso. There is an old crease that has been pressed flat, with professional repairs to several short separations along the crease and the centerfold.

References

Burden, Philip. The Mapping of North America: a list of printed maps. Rickmansworth: Raleigh Publications, 1996, #4. Brooke-Hitching, Edward. The Phantom Atlas: The greatest myths, lies and blunders on maps. London: Simon & Schuster, 2016, 130-3 & 158-61. Goss (NA) #3; Portinaro & Knirsch, pp. 64-65; Mickwitz & Miekkavaara #211-28.