Bird’s-eye-view and map of the Panama Canal issued the first year after its opening

Bird’s-eye-view of the Panama Canal

Out of stock

Description

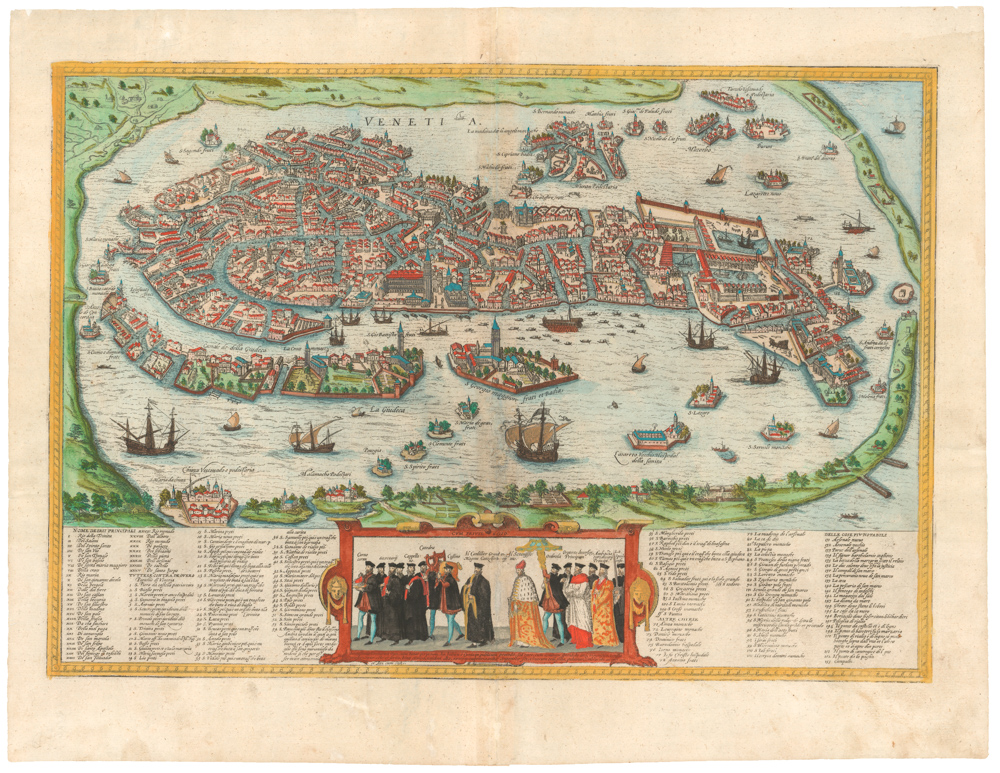

Working from the Atlantic (left) to the Pacific (right), the canal’s entrance in the Caribbean Sea can be found at Limon Bay and the port city of Colon. At the head of the bay, the Gatun Locks were to lift ships 85 feet (26 metres) up to Gatun Lake, a giant manmade reservoir newly created by the adjacent Gatun Dam. The main shipping channel, delineated by a white line, navigates the lake’s many islands (former hilltops) as it proceeds to the Culebra (or Gaillard) Cut, which is broken thought a broad hill 95 metres (312 feet) in height. Ships were then to descend though the Pedro Miguel and Miraflores Locks before entering the Pacific Ocean near Panama City. The recently relocated Panama Canal Railway skirts the left side of the canal, while a rich and mountainous jungle landscape surrounds the channel on either side.

The upper image shows the relief of the canal with the excavations done by the French, marked with red. France began work on the canal in 1881 but stopped due to engineering problems and a high worker mortality rate. The excavations done by the Americans from 1904 on is marked with black.

The Panama Canal is certainly one of the greatest and most consequential feats of engineering in world history. Over the last century, by allowing ships traveling between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to traverse the Panamanian Isthmus, it has saved immeasurable amounts of time, money (and lives), sparing vessels from the long and treacherous voyage rounding South America. The idea for a trans-isthmus canal was not new, as it had first been proposed by Emperor Charles V in 1534. However, it was not until the 19th century that such a feat was considered to be practically possible. By that time, the word’s great powers were well aware that whomever built and controlled any such canal would be conferred with immense political power and commercial advantage.

The French were the first out of the gate. Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had successfully completed the Suez Canal in 1869, ran a venture that proceeded to build a canal across the Panamanian Isthmus in 1881. This plan envisaged a sea level canal, like the Suez (i.e. without locks), that involved cutting a channel straight through the low mountains and dense jungle. This project was plagued by mass corruption, technical problems and rampant disease amongst the workers. It failed spectacularly in 1894.

The Americans moved in to aggressively to fill the vacuum, buying out the French rights and seeking to gain the backing of the Colombian government (which then controlled Panama). On January 22, 1903, the Hay–Herrán Treaty was signed which gave Bogota’s consent for the U.S. to build the canal and to control it for a period of 99 years.

However, when Colombia seemed to have second thoughts, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt concocted and supported a fake ‘independence rebellion’ in Panama that allowed the region to separate from Colombia, so becoming an American puppet state The new government of the Republic of Panama immediately approved any and all U.S. demands.

The Americans began constructing the canal in the spring of 1904, with the engineer John Finley Wallace appointed to lead the project. The endeavor was soon rocked, in 1905, by technical problems, disease and Wallace’s firing by President Roosevelt. However, it gained a strong footing when the famous railway engineer, John Frank Stevens, assumed leadership. Under his watch, a new scheme for the construction plan was developed that envisaged a raised canal with sets of locks carrying ships up to a height of 26 metres (85 feet) above sea level, before another set brought them back down to the sea on the other side. While immensely challenging, this plan was followed, and under Steven’s successor, George Washington Goethals, the project was brought to completion in the summer of 1914. At a cost of U.S. $375 million (equivalent to $ 9 billion today), it was by far the largest engineering project in the history of the Americas to date.

The first ship, the SS Ancon, passed though the canal, from sea to sea, on August 15, 1914. During the first year of the canal’s operation, 1,000 ships made this voyage, revolutionizing global shipping.

The United States retained control of the canal, formally run by the run by the Isthmian Canal Commission, and retained sovereign control of a strip of land running along either side of the channel called the Canal Zone. Control of the canal and the Zone was handed to the Panamanian government in 1979. Today, the canal has retained its vital role in global transport, and is currently undergoing an expansion that will allow it to handle mega-ships (so-called ‘PANAMAX’ class ships), which will be completed in 2016.

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Very good, soft folds, text, photography and original covers on the back.

References

![The Original Silicon Valley Map & Calendar [1994]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/NL-00909_Thumbnail-300x300.jpg)

![The Original Silicon Valley Map & Calendar [1994]](https://neatlinemaps.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/NL-00909_Thumbnail.jpg)