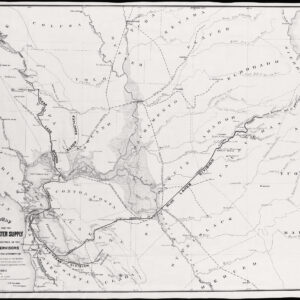

Extremely rare 1851 map illustrating San Francisco’s first water project.

Map of the City of San Francisco with its additions, Showing Two of the Routes for the Introduction of Water by the Mountain Lake Water Company. As Surveyed By Henry S. Dexter C. E. December 1851

Out of stock

Description

Rare, separately published map of San Francisco, prepared by the Mountain Lake Water Company, San Francisco’s first water project. A detailed outline of the project, its costs and specifics are set forth in an article in the Daily Alta California on October 11, 1851.

The map was created in connection with the Company’s efforts to raise money to fund construction of a canal and tunnel to bring water from Mountain Lake in the area then known as Larkin Ranch to San Francisco in 1851. In the November 4, November 8, and December 6, 1851 Daily Alta California, the company advertized $500,000 in Capital Stock, with shares selling for $50.00 each, of which 5% was required as an initial contribution.

The present map illustrates two prospective routes from which water would travel from Mountain Lake into the city, the Northern Route, which would feed into a reservoir in the North Beach area and the Pacific Street Route, which would feed into a reservoir on Cannon Hill, near the intersection of Pacific Street and Presidio Street.

The map is noteworthy as both an early map of San Francisco and for its depiction of this early water project. Of particular note is the meticulous depiction of both the San Francisco City street grid and the depiction of the existing topographical features of the city, showing a number of projected streets in areas which were then still marshlands which had not yet been dredged and filled.

The map also names a number of the earliest wharves in the city, including:

Taylor Street Wharf

Carr’s Wharf

Cowell’s Wharf

Law’s Wharf

Buckelew’s Wharf

Cunningham Wharf

Broadway Wharf

Pacific Wharf

Central Wharf

Market Street Wharf

In all, an exceptional large-format map of the city, printed in 1851 in New York City, in conjunction with the company’s efforts to raise funding for the initial construction. As noted below, $500,000 would be raised, but the project would end prematurely, without ever delivering any water to the city.

The Mountain Lake Water Company

The first steps toward introducing a water supply to San Francisco were taken on June 1, 1851, when the Boards of Aldermen granted Azro D. Merrifield and partners a franchise and on August 14, 1851 Merrifield and partners incorporated the Mountain Lake Water Company. The source of the water was Mountain Lake, a 7 acre lake at the head of Lobos Creek, in the southwest portion of the US Military Reservation at the Presidio. The Company initially proposed a gravity conduit from the Lake down Lobos Creek and then along the waterfront to a proposed reservoir at North Beach.

Merrifield left San Francisco shortly after the approval of the franchise, assigning the rights to Colonel W.G. Wood. The initial venture and several later re-organizations of the Company failed.

The following is excerpted from sfgenealogy.com in a section called Deacon’s Follies:

THE MOUNTAIN LAKE FOLLY

In the very early days of San Francisco, only two years after the argonauts of ‘49 arrived here, some enterprising gentlemen, gifted more with long purses than prophetic foresight, came to the conclusion that the city needed a water system.

They invested about $300,000 in tunneling under the hills of Mountain Lake, near the Marine Hospital, to Larkin and Pacific Streets.

It was a big brick and concrete tunnel, big enough for a small man to walk through without ducking his head, and it is still there.

For a mile or more its runs under the center of Pacific Street, then cuts into the hills through the Presidio reservation, and opens out within a hundred yards or less of Mountain Lake.

It is a very expensive tunnel, very well constructed, but of no utter use in all the world. Nor was it ever of any service. Shortly after its completion the whole scheme collapsed, as it should have done in its infancy.

It is a very interesting story and not known to the younger people of this generation. It was the first movement towards securing a water supply for San Francisco, and the prime movers in the scheme were John Middleton, Ferdinand Vassault, A. D. Merrifield and William G. Wood.

Of these only Ferdinand Vassault is alive today, and he is a very old, white-haired gentleman, with a remarkable facility of speech and excellent memory for one so old.

He told the story to a CALL man in the following sequence: “In 1851 I bought the eighty-acre tract in which Mountain Lake is situated,” he begins, “from Edward M. Parker, who had located there and carried on a small vegetable farm. The land lies in the rear and adjoining the Government reservation.

“Governor Samuel Purdy soon afterward became the part owner of and the representative of the whole of an undivided one-half of the tract of eighty acres.

“Major Robert Allen, then Quartermaster-General for the Pacific Coast, William G. Wood, John Middleton, A. D. Merrifield, Governor Purdy and myself then organized a company for the purpose of utilizing the water of Mountain Lake in supplying the city of San Francisco. The corporation was known as the Mountain Lake Water Company.

“June 1, 1851, we secured a franchise for building the tunnel and laying our mains. Then at a cost of $280,000 we built a big brick tunnel 5 feet by 4 1/2, interior dimensions.

“Major Allen, Governor Purdy and myself were the principal owners of both the land and the company. The surveys for the water system were made by John Morris and a noted civil engineer of that time named Hotalliog. When the tunnel was built and the surveys all completed we found that we had invested altogether $280,000. About $500,000 was still needed to complete the enterprise, and this amount we could not borrow on bonds here save at a frightening high rate of interest.

“So Nathaniel Bennett, Governor Purdy and Mr. Wood went on to New York to negotiate the loan. Through the house Horace Ketcham & Co. the loan was finally engineered at a reasonable rate of interest, and a day was set upon which the papers were to be signed and the money placed in the bank subject to our order.

“When the day arrived for the consummation of the deal Charles O’Connell, who was the attorney for Horace Ketcham & Co., after examining our franchise and act of incorporation, raised the technical point that the latter document did not empower our corporation to raise money on bonds.

“It was then agreed that the matter should stay over until the Legislature of California convened again, when the technicality should be remedied and the money loaned without further delay.

“That year the Assembly met at Vallejo and the great water-front question was brought up. There was great excitement over the settlement of this controversy and as a consequence all lesser matters were lost sight of.

“Hall McAllister, who was out here then, Mr. Wood and myself went to Vallejo to try to resurrect our forgotten cause.

“At that time I had organized a company with certain Russian officials for the purpose of bringing ice down here from Sitka. We wanted a special law passed enabling the Russian Government officials to become partners with us in the enterprise.

“In this matter we were successful and the best legal authorities on the coast assured us that in this enactment the very point raised by the attorney for Horace Ketcham & Co. was fully covered. We were satisfied with that and did not feel like asking the Legislature to duplicate its motion for our especial benefit.

“But when the New York attorney looked into the question he came to the opinion that the point he had raised was not covered at all by the Russian law.

“As so the matter of the loan dropped entirely. We had already lost a good deal of money in the water company as none of us could afford to get further involved in it the whole thing fell through.”

In 1857 John Seuslcy A. W. von Schmidt and A. Chabot organized the San Francisco Water Works. Their plan was to run off the water from Mountain Lake through Lobos Creek and carry the water down to the city in wooden flumes.

But on testing the capacity of Mountain Lake, which is the outlet of a deep spring, they found it inadequate to the demands, and the principal supply for the water system came instead from Lobos Creek. To this day the system founded by these men is in operation, and one may follow the course of their wooden flumes along the coast line from Lobos Creek till it passes Fort Point and is lost under the hill several miles from its source.

In 1865 Spring Valley became the successor of the San Francisco Water Works, but it still employs the Lobos Creek flumes and system.

The Mountain Lake Water Company’s project met with less favor from succeeding water-supply companies, and even its costly brick aqueduct has never been turned to account.

This fact alone seems to argue the folly of the scheme. The civil engineers of to-day smile derisively when asked for an opinion as to the utility of that tunnel or the practicability of using the Mountain Lake spring as a water supply.

Of course, the Larkin street end of the big aqueduct has been covered up long since, and the only sign left now of the pretentious water system is a grass-grown trench running from Mountain Lake about 200 yards to the mouth of the brick aqueduct.

But the mouth of the aqueduct itself is filled with tons of earth that fall over it so very long ago that to-day it is grown over with weeds and grass, and the bright yellow poppies blooming there seem to have ever grown and thrived in the outlet of a useless tunnel that cost $280,000.

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Flattened and cleaned, with some minor restoration and infill at the fold intersections. Some minor fold discoloration.

References

The map is extremely rare. Prior to our acquisition of the map, only one example of the map had appeared at auction (Streeter Sale, 1968, Lot 2707, sold for $110).

OCLC locates copies in the California Historical Society, Bancroft, the Huntington Library and Yale.