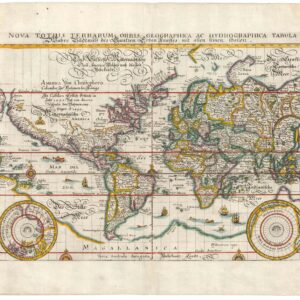

One of the earliest world maps available to a collector, based on a map by the mapmaker who named America.

Diefert Situs Orbis Hydrographorum ab eo quem Ptolomeus Posuit.

$8,500

In stock

Description

An adaptation of one of the earliest depictions of the Americas ever made: a Waldseemüller world map that was drawn in 1505, two years before his famous 1507 masterpiece and only a handful of years after the early voyages to North America and the discovery of Brazil by Pedro Álvares Cabral.

Click here to see a video we made about a 1541 example of this map.

This exquisite early 16th-century map of the world by Laurent Fries is not only one of the earliest obtainable maps to show the New World but one of the earliest ‘complete’ world maps available on the market. It is one of three world maps issued by Fries in his revised and compacted version of Martin Waldseemüller’s famous Ptolemaic atlas from 1513 (and reissued in 1520), entitled Claudii Ptolemaei Alexandrini Geographicae. The three world maps included in the Fries edition were direct adaptations of maps originally issued by Waldseemüller. Each map serves a different purpose, making it an ideal item to collect individually or as a cluster.

This is the third map in the Fries World Map cluster. While the map itself has been directly adapted from Waldseemüller, this is one of the maps that Fries saw fit to elaborate by adding various symbolic and decorative elements. Most noticeable among these is perhaps the insertion of five exotic kings seated on their respective thrones. In the northernmost parts of Finnmark, we find the King of Russia, the only European ruler depicted on the map. In Africa, similar thrones are found in Egypt and Ethiopia — ancient loci of known and respected kingship —.

In contrast, in Asia, we see the kings of Traprobane (Sri Lanka) and Mursuli (modern Thailand) included, presumably due to their status as vital trading partners in the East. In these cases, the depicted regents do not represent living rulers or concrete political entities of the mid-16th century. Instead, they manifest just how old this particular vision of the world is. Having been conceptualized in the ancient world, these kingdoms represent the Greco-Roman understanding of the known world’s political division.

In the northwestern corner of the map is a strangely elongated peninsula representing Greenland. In the 16th century, Norwegian and Icelandic whalers would sail on the Greenlandic coasts during summer. However, despite this, it was still a largely unknown and frozen wasteland to most European geographers. The difficulty in establishing what land was and what was ice is evident in this map, in which the label Gronlanda has been applied to both the long and thin peninsula and the seemingly open waters to the northwest of it. Fries imbued this peripheral European space with new mystery and life by depicting an elephant in the waters between the two Gronlanda labels. Whether this was pure fantasy or grounded in early findings of Mammoths is challenging to say. Still, seeing that the associated text underlines the impressive length of its dentures, it is perhaps most likely to simply be part of a growing 16th-century tradition of bestiaries in maps.

One of the most exciting features of Asia in Ptolemaic maps is the warped and oversized depiction of some features over others. An example is seen immediately to the right of southern India, where we find an oversized depiction of Sri Lanka. In this case, the exaggerated dimensions are undoubtedly due to the age-old significance and status of the island as a hub of international trade. Not only did much of the maritime Silk Road hinge on Sri Lanka as a central node in a vast mercantile network, but European travelers had been frequenting the island for commercial purposes since Roman times.

A cartographically more significant warping is found in the dramatic and curved extension of the Malay Peninsula. Known among collectors and specialists as ‘the Dragon’s Tail,’ this feature was widely used to show a schematic representation of the still largely unexplored and geographically complex Southeast Asian Archipelago. Henricus Martellus Germanus, a German mapmaker in Florence in the 1490s, initially proposed the Dragon’s Tail model. By extending the easternmost peninsula and curbing it inwards, he devised a reasonable compromise to resolve the long-contentious issue of Ptolemy’s land bridge connecting southeast Asia and southern Africa.

The Dragon’s Tail constitutes a transitional element in the shift away from a Ptolemaic view of world geography, which perceived the Indian Ocean as an enclosed space, bounded on its southern side by a mythical land bridge between the African and Asian continents. Sailors had rejected this for centuries, but cartographers did not broadly accept it until a feasible alternative model could be formulated. While there was a dawning awareness of the Antarctic shelf, it was also known not to form the type of physical connection hypothesized by Ptolemy. The Dragon’s Tail was an acceptable compromise in that it evolved from the old model of the world but took the increasing amount of new information into account. Finally, the broad swoop of the Dragon’s Tail may also reflect an early awareness of the cultural and geographical coherence of the Southeast Asian Archipelago.

For its part, Africa has roughly the correct outline, with both the Horn and Cape depicted. Still, it mainly lacks toponyms and replicates several myths about Antiquity. The Nile, in many ways the cradle of Western civilization, has always been a contentious topic of geographic debate. According to Ptolemaic tradition, the great river’s source is in a tremendous interior range known as Mons Lunae, or Mountains of the Moon. In this map, these have been depicted further south than usual and flow into two great lakes, dating back to Ptolemy’s original descriptions and possibly representing early conceptions of Lake Victoria and Lake Albert.

From the perspective of importance, this map is perhaps the most interesting of the three Fries maps for collectors. Even though it uses the Ptolemaic vision of the world as its foundation, the easternmost parts of the New World have also been included on the map. Scholars largely agree that Waldseemüller’s version of this map was completed around 1505-1506, which means that it was compiled and cut before the publication of his famous landmark map of the world, Universalis Cosmographia (1507), in which America received her name for the first time. One might consequently argue that this particular depiction of the Americas predates Waldseeüller’s and Apian’s famous world charts. However, unlike one of the other Fries maps from this atlas, the New World is not named or given the more common label of Terra Incognita. The only two toponyms provided for the New World are located in Brazil and read Caput S. Anas (Head or Point of St. Anas) and Terra Papagalli (Land of Parrots). It has not been possible to ascertain the exact locations to which these toponyms refer.

Context is everything

The French cartographer Laurent Fries (Laurentius Frisius), a Rhinelander born in Mulhouse in eastern Burgundy, close to the German and Swiss borders, drew the current map. As a young man, Fries studied medicine and mathematics at the universities of Vienna, Montpellier, Padua, and Colmar before settling in Strasbourg around 1518 to become a physician and medical publisher.

In the following years, he gained employment as a draughtsman working for Peter Apian on his extraordinary heart-shaped map of the world (published in 1520). As part of this work, Fries carefully studied the maps of local master cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, who had published his most seminal world map as early as 1507 and had subsequently complimented this achievement with a significant Ptolemaic-style atlas issued in 1513 (and revised in 1520). Fries’ fascination with Waldseemüller’s maps brought him into contact with the German printer and publisher Johannes Grüninger. This was a significant turning point — Grüninger was the formal publisher of a group of local scholars known as the St Die Gruppe, which counted prominent members such as Walter Lud, Martin Ringmann, and Martin Waldseemüller.

Strasbourg was famous as a center for cartography at this time, home to two of the world’s best mapmakers: Martin Waldseemüller and Peter Apian. The two set new standards for the compilation of maps and charts, but Waldseemüller, in particular, revolutionized how the world was rendered. Waldseemüller’s hugely influential world map from 1507 would apply the term ‘AMERICA’ for the first time. In an associated text, he explained that the origin of the name pertains to the explorations of Amerigo Vespucci. This was a controversial claim at the time and one that cartographic scholars still debate today. The critical thing to note here is that when Waldseemüller issued his version of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia in 1513, he changed this label back to ‘Terra Incognita.’ Despite this semi-retraction, the impact of his world map was so profound that the name stuck in perpetuity.

Martin Waldseemüller died in 1520. His death was a significant loss to mapmaking, local publishing houses, and Strasbourg itself, as his output had become an essential source of income and prestige. Consequently, it was quickly decided to reissue the Waldseemüller atlas in a new edition in the hope that it would sustain interest and income for a time. Grüninger got his hands on the 1520 edition and was keenly interested in filling the gap produced by Waldseemüller’s death. An agreement was reached among several local publishers that a revised and compacted version of Waldseemüller’s monumental tome was in order, and it was Laurent Fries who was hired as the cartographic editor-in-chief for this project. The basis for this decision should probably be sought in his knowledge of Waldseemüller’s work and his close professional association with Peter Apian. Fries started his independent cartographic career by re-drawing Waldseemüller’s famous world map and publishing it in reduced form in Caius Julius Solinus’ Enarrationes, published in Vienna that same year.

Even though Fries was not a geographer by training, he understood many of the mechanisms and skills behind compiling convincing and impacting maps from his time working for Apian. Under Fries’ direction, many of Waldseemüller’s maps were now re-sized and redrawn. While the maps remained unchanged in most respects, Fries would often add text such as historical notes and legends or embolden the map with illustrations of prominent political or mythological figures and a bestiary of land and sea creatures. Since the aim was to compile a more compact version of the atlas, Fries also introduced the idea of printing text on the verso of the maps and not on separate sheets like Waldseemüller had done. Finally, Fries included three new maps in his atlas, which depicted Southeast Asia and the East Indies, China, and the World, respectively. While these were not taken from the 1513 atlas, the geographic information was adapted more or less directly from Waldseemüller’s Universalis Cosmographia, stressing just how seminal he remained even after death.

Chronology of the Fries’ Editions

Fries’ atlas never became the huge commercial success it was intended to be despite having a more portable format and a more affordable price than Waldseemüller’s original; troubles with distribution and growing competition made sales of the initial edition an uphill battle. There was a widespread idea that the Fries atlas was privileged with better and more up-to-date geographical knowledge. However, this was hardly the case, as Fries built his maps almost exclusively on Waldseemüller’s originals.

Notwithstanding the first edition’s lack of popularity, four distinct and formal editions of the Fries atlas were issued over the next twenty years. The first original atlas was published in Strasbourg in 1522, only two years after Waldseemüller’s death and the publication of the final edition of his Ptolemaic atlas. The first Fries edition consisted of fifty woodcut maps, including one of the earliest known maps to label the New World as ‘America.’ While this was copied directly from Waldseemüller’s Universalis Cosmographia, the tight chronology of these editions and the unavailability of Universalis Cosmographia on the market meant that the Fries editions constitute the earliest acquirable maps to name America. It has been estimated that circa 1000 copies of Waldseemüller’s map 1507 map were issued. Of these, only one known copy survives. This was discovered by Josef Fischer in 1901 in the attic of Wolfegg Castle in southern Germany and was purchased by the Library of Congress a hundred years later.

Despite its ambitions and the success of its precursor, Fries’ first edition of the atlas was not a huge commercial success, and the circle of responsible publishers soon felt a need for critical amendments. Thus, only three years after the atlas’ initial publication (1525), a new edition was issued. This contained an entirely new text by Wilibald Pirkheimer (adapted from Johannes Regiomontanus) but the exact same maps as the first version.

In 1531, Grüninger died, and his publishing house was carried on by his son. Many of the printing plates owned by Grüninger were sold to other publishers to keep the business afloat. The materials for the Fries atlas ended up with two brothers in Lyon, Melchior and Gaspar Trechsel. They issued a new 1535 edition with a freshly revised text written by the radical physician and free-thinker Michael Servetus. Consequently, the maps from this publication have become known as the Servetus Edition.

Despite the maps undergoing very little change, this version of the Fries atlas is surrounded by drama. Servetus was tried as a heretic and burned at the stake following its publication. His crime, supposedly, was the following derogatory comments made about the Holy Land in the verso text of the Holy Land map. Roughly translated, it reads:

“And so, most excellent reader, you should realize that in error and by pure exaggeration, a reputation for excellence was bestowed on this land; however, the testimony of merchants and travelers detracted from this inhospitable and barren land, which lacks any attraction, and reputation for excellence. Therefore, this so-called promised land should not be praised in a vernacular language.”

There is no doubt that Servetus was a man of the Enlightenment and, as such, had been a vociferous critic of the religious establishment — particularly of Calvin himself — for decades before being persecuted for this particular crime. Ironically, however, the comments were not part of Servetus’ new text. Instead, they were elements copied from the original Strasbourg editions. Yet Servetus had made powerful enemies and had even managed to escape an arranged Inquisition trial once before. So when Servetus confronted Calvin in person during a sermon in Geneva, he was arrested and imprisoned again.

During his trial, the fact that the comments were not his but simply adapted from the earlier editions was stressed emphatically but did nothing to sway the prosecutors and judges. On October 27th, 1553, Michael Servetus was burned at the stake for blasphemy. He suffered a final denigration when he discovered that the pyre upon which he would burn was composed of part of his books, manuscripts, and maps. For this reason, the maps from the Servetus Edition are so rare on the market.

Even though apostasy and descent were generally met with mercilessness from all branches of the Church, Servetus had published extensive critiques of both church and gospel in his youth, eventually landing him such powerful enemies that he was forced to flee to Paris. The fact that he was only caught in the end due to traveling to Geneva to fulminate against his powerful arch-enemy in person shows a degree of fanatic recklessness. Nevertheless, the brutal persecution of a man of knowledge and letters sent shockwaves throughout the cartographic communities of Europe. The 16th century was an age of exploration and experimentation, but new knowledge horizons could not be sought without some backlash. Consequently, when Gaspar Trechsel funded the fourth and final version of Fries’ atlas, published in Vienne in 1541 (i.e., twelve years before Servetus was sentenced to death), the new editor, Dauphiné, made sure that the controversial comments were stricken.

In sum, the trajectory along which 16th-century cartography evolved meant that Waldseemüller, in many ways, remained the great pioneer in mapping the Americas. This was undoubtedly because of his brilliance as a cartographer, but most of all because his Universalis Cosmographia became the chart that ultimately gave America her name. And yet the extraordinary rarity of Waldseemüller’s 1507 map, along with his decision to remove the America label from the continent in his 1513/1520 atlas, meant that the Fries edition of Waldseemüller’s maps constitutes the earliest obtainable copy of a map actually to name America. Among the four Fries editions, in which the maps undergo very few changes, the original 1522 and the Servetus editions are the rarest. Moreover, due to the dramatic ‘Enlightenment struggle’ story associated with the third edition, it has also become a symbol of the Enlightenment’s resistance to the Church’s brutal insistence on widespread ignorance.

Cartographer(s):

Laurent/Lorenz Fries (ca. 1485-1532) was born in Alsace circa 1490 and studied medicine and mathematics at a number of European universities. He was trained as a physician but was also keenly interested in cartography and medical publications. From 1518-19 Fries is mainly based in Strasbourg, where he was commissioned to compile the first edition of Waldseemüller’s atlas after his death in 1520.

Condition Description

Strong, nice impression. Some lightening along the centerfold and two remnants of hanging tape on the verso.

References