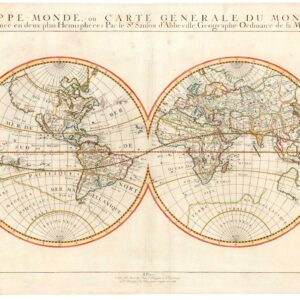

Merian’s endlessly fascinating 1646 world map.

Nova Totius Terrarum Orbis Geographica Ac Hydrographica Tabula…

$1,700

1 in stock

Description

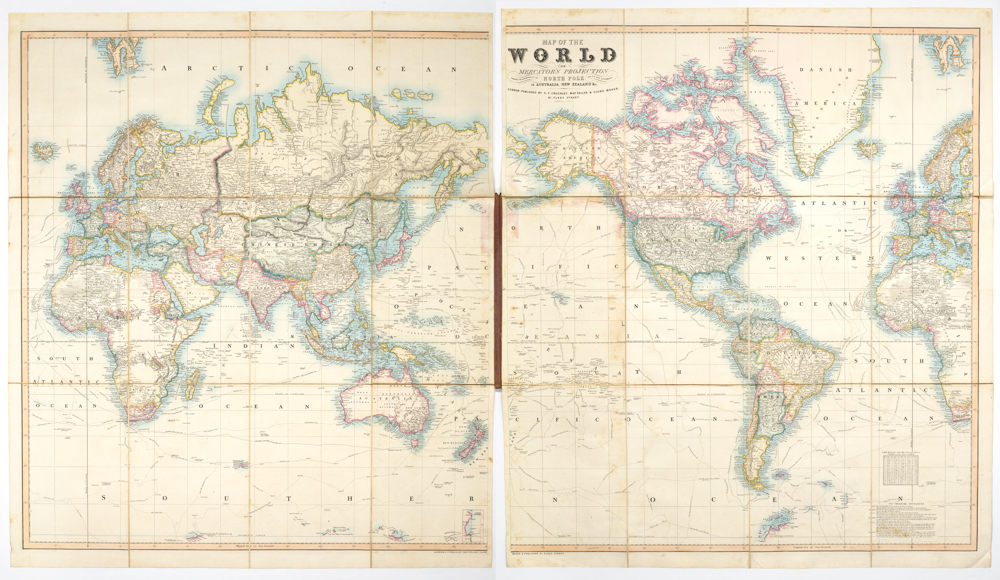

A gorgeous representation of the world as it was understood in the mid-17th century, this is Matthäus Merian’s 1646 world map on the famous Mercator Projection, published in Frankfurt as part of Merian’s Neuwe Archontologia cosima. With beautiful hand color and fine engraving, the mapmaker has succeeded in visualizing both new discoveries and long-standing cartographic misconceptions. The map is based on Willem Blaeu’s world map from 1606, but its Gothic flourishes mark this as a distinctively German aesthetic achievement.

Merian makes direct reference to Christopher Columbus on the map, and the New World had of course long been discovered at the time of its publication, but the cartography still consists of significant gaps, especially for interior regions and unexplored coasts. The overall shape of South America, for example, is relatively accurate, but inland we find Lake Parima and Laguna de Xarayes, both associated with El Dorado, the mythical city of gold.

For North America, the Eastern Seaboard, already home to colonies like Jamestown and Plymouth, as well as a number of Spanish fort settlements, is depicted in detail. But again as we move inland, we begin to find major lacunae (e.g. the Great Lake are missing completely), and mythical kingdoms like Quivira, supposedly home to a series seven of fabulously wealthy cities.

On the west coast, California is given an elongated form that belies a lack of accurate surveys. The place names along the coastline are plentiful, and even the Sierra Nevadas have been labeled. But the stretching is such that Cape Mendocino is found at 50ºN latitude, nearly 10º too far north. The further north we travel, the more speculative the cartography becomes; the simple reason being that these challenging waters had yet to be fully explored at the time the map was published. The map provides a window onto an era before Vitus Behring had traversed the straight that now bears his name. Our mapmaker instead uses the name Anian, which comes directly from Marco Polo centuries prior.

In both a north pole centered inset and on the main map itself, the existence of a northwest passage is left ambiguous; in fact, Merian has cleverly placed a large block of text in North America to hide his lack of knowledge. Likewise, above Europe, the possibility of a northern passage remains, with Nova Zembla only partially mapped according to the discoveries of Willem Barentz at the end of the 16th century.

The map’s portrayal of East Asia also demonstrates the lack of European exploration in the region. Korea is drawn as a long vertical island, and Japan is a primitive blob; this being before crucial reports from Jesuit missionaries began clarifying the layout of the Japanese archipelago. The Philippines, too, have been mis-mapped, and are much too large.

Moving to the Southern Hemisphere, we see the African interior remained largely unknown to European cartographers in the 17th century. Many of the place names and rivers are based on rumor rather than scientific exploration, and Merian follows a long speculative tradition of identifying two large lakes in southern Africa as the source of the Nile. In addition, one of the oldest cartographic misconceptions – the existence of a massive southern land that balanced out the globe – is a prominent feature, both in the main map and in an inset at bottom right. Often called Terra Australis, here it is also labeled Magellanica after Ferdinand Magellan. This mythical land is again juxtaposed by real discoveries, including the Solomon Islands and the Straights of Le Maire.

Added to all that, we see the mythical islands of Brazil and Frisland in the Atlantic – clearly, this is a map that is jam-packed with history and intrigue!

Cartographer(s):

Matthäus Merian (September 1593 – 19 June 1650) was a Swiss-born engraver who worked in Frankfurt for most of his career, where he also ran a publishing house. He was a member of the patrician Basel Merian family.

Early in his life, he had created detailed town plans in his own unique style, for example plans of both Basel and Paris (1615). With Martin Zeiler (1589 – 1661), a German geographer, and later (circa 1640) with his own son, Matthäus Merian produced a collection of topographic maps. The 21-volume set was collectively known as the Topographia Germaniae and included numerous town-plans and views, as well as maps of most countries and a world map. The work was so popular that it was re-issued in many editions. He also took over and completed the later parts and editions of the Grand Voyages and Petits Voyages, originally started by Theodor de Bry in 1590. Merian’s work inspired the Swedish royal cartographer, Erik Dahlberg, to produce his Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, which became a cornerstone in European mapping.

After his death, his sons Matthäus Jr. and Caspar took over the publishing house. They continued publishing the Topographia Germaniae and the Theatrum Europaeum under the name ‘Merian Erben’ (i.e. Heirs of Merian). Today, the German travel magazine Merian is named after him.

Condition Description

Excellent.

References

OCLC 216757362. Shirley, Rodney W., The Mapping of the World: Early Printed World Maps 1472-1700, #369.