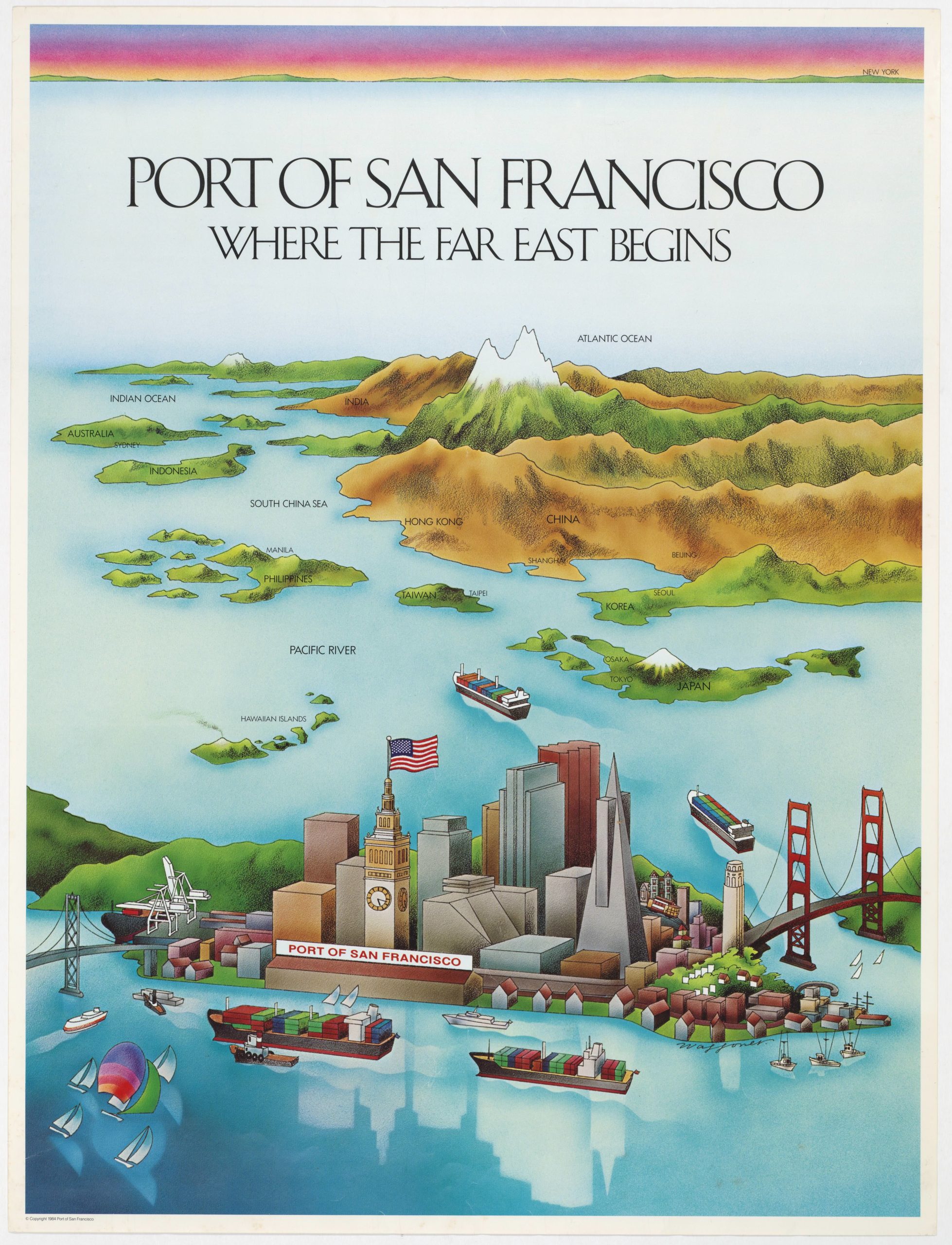

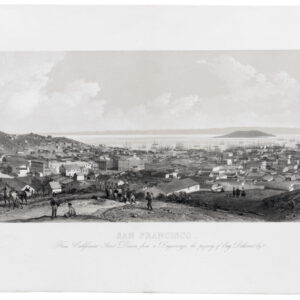

A stunning retrospective of early San Francisco, painted by a highly skilled anonymous artist of America’s Continental School.

Yerba Buena.

$10,500

1 in stock

Description

This unique piece of San Francisco history is a gorgeous gouache-painted rendition of the city before the Gold Rush. It is labeled ‘Yerba Buena’ by the anonymous artist and is oriented to the east, with Yerba Buena Island at center and the hills of the East Bay in the background beneath a blue sky.

There can be little doubt that this is an authentic 19th-century view, as all the elements, from the impressionistic style and seemingly effortless brush strokes to the canvas patina and compositional elements, support this interpretation. As explained below, we interpret this painting as an early 1870s romanticized retrospective of what San Francisco would have looked like circa 1847, before the massive influx of fortune-seekers who came as a result of the Gold Rush.

From Yerba Buena to San Francisco

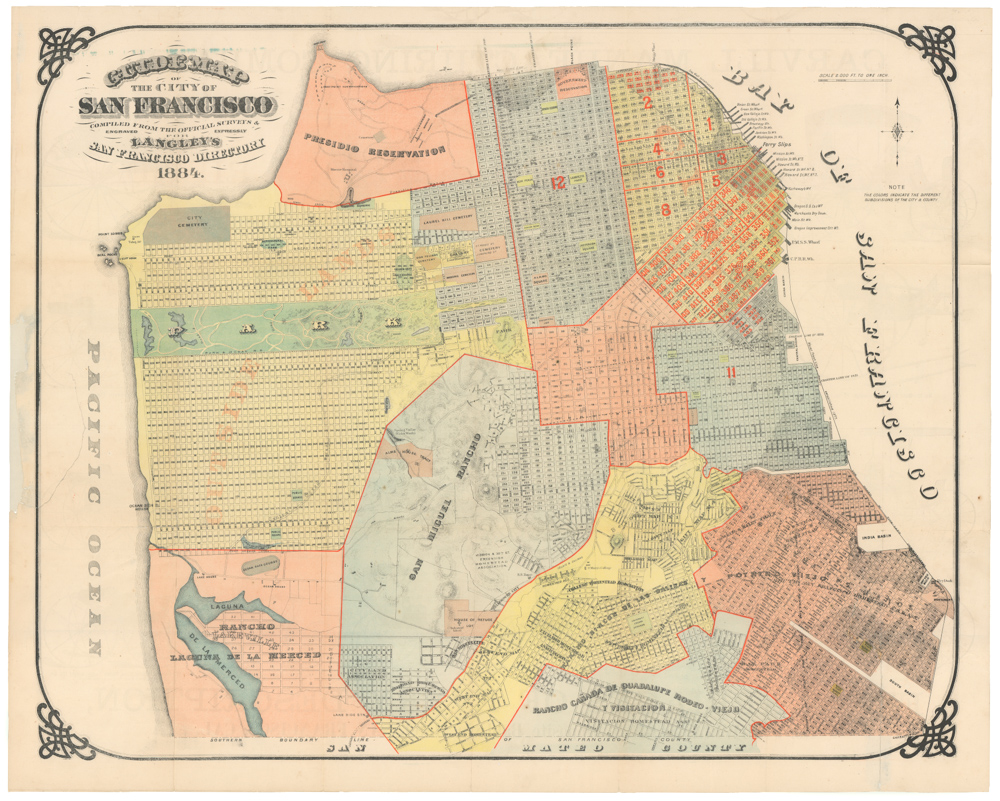

The small port village of Yerba Buena officially changed its name to San Francisco on Jan. 30, 1847. The swap occurred in the midst of the Mexican-American War and at a time when nearby cities like Benicia were vying to become the principal port on San Francisco Bay. Taking the same name as the Bay itself assured the two would be forever linked.

We know from numerous sources, from newspapers to personal letters, that the old name did not linger for long. By the time the Gold Rush took off in 1849, the new name of San Francisco had entirely replaced the old Yerba Buena designation. Therefore, it is unlikely that the Yerba Buena title of this painting resulted from colloquial resilience. Instead, the artist was likely attempting to recreate an atmosphere that was not very distant in time but which the city’s massive development in the 1850s and 60s had wholly effaced.

An age of progress and nostalgia

The development of San Francisco from village to city happened with such speed that even by 19th-century standards, it quickly became an icon of modernity and progress. Everything in San Francisco exploded following the Gold Rush, from its demography to real estate prices, and the urban landscape expanded at a rate not seen anywhere else in the United States. Because of this impressive expansion, and perhaps further augmented by the Bay Area’s natural beauty, San Francisco became a magnet for artists seeking to capture the rapidity with which modernity was transforming America. The city was the icon of an age in which landscapes that had remained static for centuries were utterly transformed in the span of a generation. This painting is an artistic attempt at recording this development.

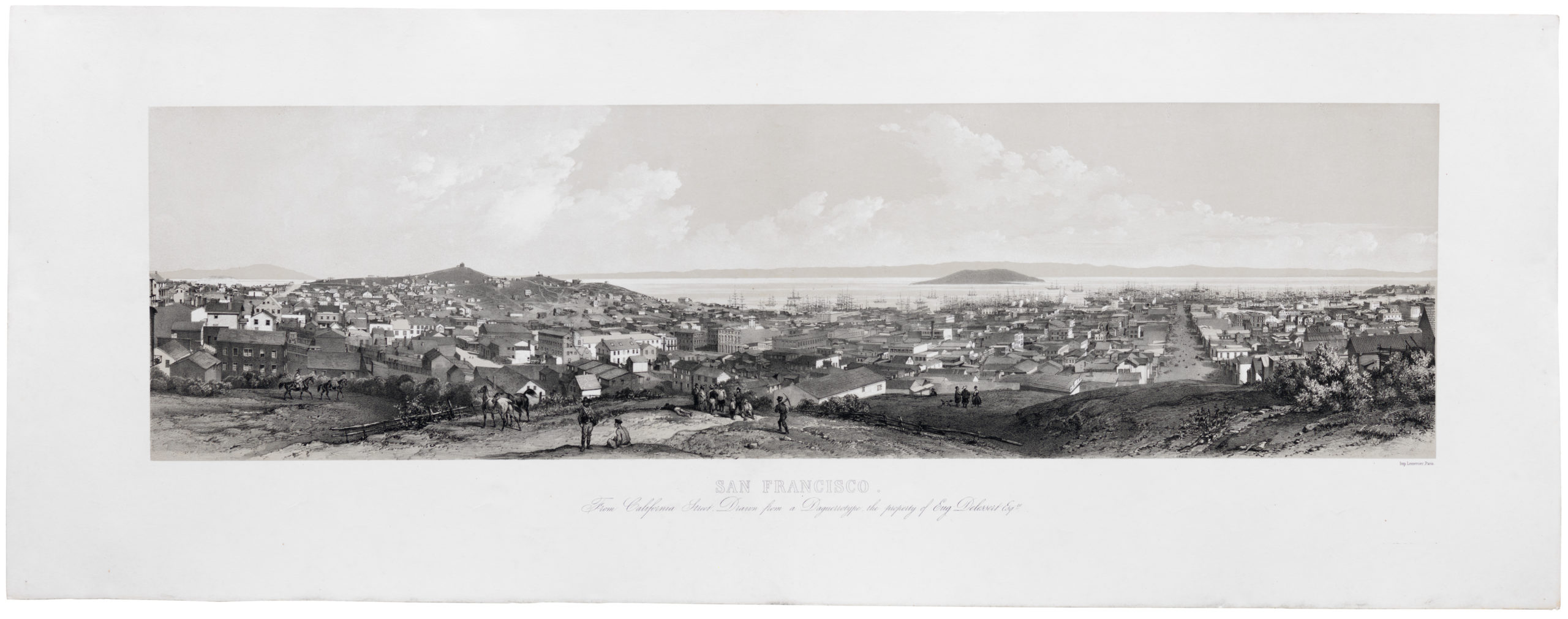

San Francisco is known for the 1906 earthquake, which devastated the city. But 1906 was hardly the first time large parts of San Francisco were destroyed. Between December 1849 and June 1851, the city endured at least seven severe conflagrations, of which the sixth was the most destructive. On the night of May 3rd, 1851, a fire blazed through town, incinerating about three-quarters of the city’s infrastructure in ten hours. We have a handful of visual records documenting what the city looked like before this catastrophe, including the famous ‘Sea of Masts’ daguerreotype, but these are not correlative to the landscape shown in our painting.

The key to understanding the composition is found in the configuration of the town itself, which constitutes an amalgamation of the contemporary with an envisioned past. It was possibly conceived in part from an early drawing, as was the case for C.P. Heininger’s lithograph portraying San Francisco in 1846-47, published in 1884. Heininger’s view was also a historical retrospective but was firmly anchored in a realistic drawing of the Yerba Buena settlement from that time. Nevertheless, our painting deviates significantly from Heininger’s more accurate account.

The appearance of the individual buildings suggests a more developed townscape, sporting elaborate facades, multiple stories, and tiled rather than timber roofs. The main open space is likely a representation of Portsmouth Square, its appearance showing the type of central plaza that dominated most Mexican/Californian villages in the early 19th century. While the individual structures are more representative of the architecture when the painting was executed, their combined setting harkens back to earlier times, before the population exploded. Similarly, while the types of ships in the bay align with an 1847 reality, the sheer number is not.

A clue for dating

In trying to date the creation of this extraordinary work, we turn to Yerba Buena Island, also known at various times as Goat or Wood Island. While the island in the bay was originally the site of an Ohlone fishing camp, by the mid-19th century, it was all but abandoned to goats. In our painting, however, it is evident that several quite large structures are present along the island’s southwestern coast.

These buildings appear to be the Army Post Camp Yerba Buena Island (a.k.a. Army Post Camp Decature, U.S. Engineer Depot Yerba Buena Island, or the US Quartermaster Depot). The base structures were erected in the early 1870s after the Union Army had voiced significant concerns about the possibility of raiding Confederate warships slipping past Fort Point and Alcatraz Island on a foggy night.

Construction of the buildings was nevertheless only started in the early 1870s and presumably only after March of 1871 when the Subcommittee on Private Land Claims rejected a claim of the island’s purchase by Thomas H. Dowling. The army base complex was crowned with the erection of an octagonal lighthouse in 1875, a landmark that still stands today at the end of Hillcrest Road. The painting does not show anything that might resemble this iconic and recognizable structure, suggesting that our artwork most likely was produced between the first buildings going up and the completion of the lighthouse (i.e., between 1871 and 1875).

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Excellent. Framed.

References