The first printed map to use a full globular projection, and the first world map to accurately depict the course of the Rio Grande flowing into the Gulf of Mexico.

[World] Continentem Dudum Notam Componebat & Continentem Noviter Detectam Componebat.

$6,500

1 in stock

Description

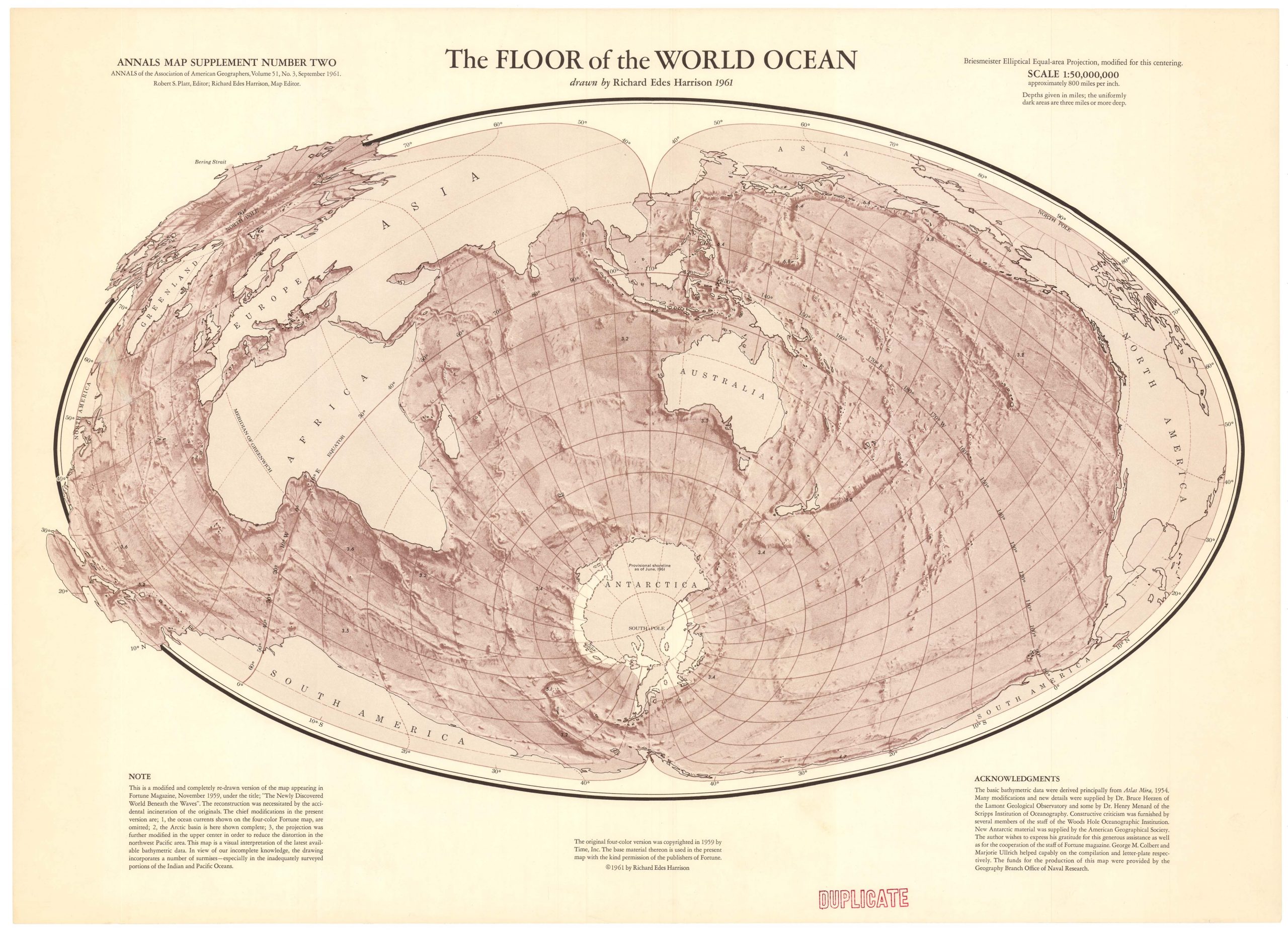

It is only recently that collecting circles have begun to realize what a small group of scholars specializing in the history of cartography have known for some time: that this iconic double hemisphere world map constitutes a milestone in the development of historical mapping and was one of the most critical world maps published in the 17th century. It was produced by Sicilian geographer and mapmaker Giovanni Battista Nicolosi on a commission from the Vatican and constituted a pioneering innovation in how the physical world was portrayed. This entirely new perspective on geography was groundbreaking and quickly adapted across the cartographic plane. It has consequently come to be known as the ‘Nicolosi projection.’

In addition, Nicolosi’s map is the second printed map on a hemispheric projection to show the Pacific Ocean at the center of the world, preceded only by the 1598 Francis Drake map.

Nicolosi and the Dell’ Ercole e Studio Geografico

Giovanni Battista Nicolosi (1610-1670) was a Sicilian priest and cartographer working for the Vatican in Rome. Motivated by the ground-breaking maps of French cartographer Nicolas Sanson (especially those in his 1653 Index Geographicus), the Propaganda Fide of Rome commissioned Nicolosi to produce an atlas that could rival Sanson’s. Over the next seven years, Nicolosi labored intensively to meet his employer’s demand, and the outcome would be one of the most essential Italian atlases produced in the 17th century.

Nicolosi’s Dell’ Ercole e Studio Geografico was published in Rome in 1660 and again in 1671 as a posthumous Latin edition. The title referred to a comparison between the labors of Hercules and those he had sustained to complete a full description of the earth. In the Ercole, Nicolosi presented large four-sheet maps of all the continents as they were known in the 1650s (Africa, North America, South America, Europe, and Asia – twenty-two plates in all). The atlas also contained an essential double map of the world, which incorporated many of the continental map innovations on a global scale (e.g., both the dubious depiction of the Niger River, as well as the first relatively accurate inclusion of the Rio Grande). Consequently, both the 4-sheet maps of the continents and the two-sheet map of the world have become highly sought after by collectors and institutions alike.

The Ercole was dedicated to Giovanni Battista Borghese and consisted of two folio volumes printed by Vitale Mascardi. Composed of no less than 22 maps with associated explanatory text, the Latin edition of the Ercole (1670) allowed Nicolosi’s ideas to be fully integrated into the cartographic mindset of Europe. In time, the Ercole became one of the most critical geographical works of the 17th century. This was partly because of the incredible archives and sources available to Vatican scholars in the 17th century. Still, the main reason was that Nicolosi approached global mapping in a novel way. He combined the traditions and perspectives of 16th-century Roman and Venetian mapmakers with the latest approaches of contemporary greats such as Nicolas Sanson. This amalgamation of traditions and styles meant that Nicolosi could come up with an entirely new way of portraying the world – especially when it came to larger landmasses where the curvature of the Earth affected how such terrain could be portrayed correctly.

Nicolosi was the first to employ the so-called pseudo-perspective projection in which the established meridians were perfected by complimenting circular parallels. Over the following decades, and especially during the early 18th century, this projection technique – also known as the globular projection – became increasingly popular and was applied by seminal cartographers such as Guillaume de l’Isle and Aaron Arrowsmith. In the decades after Nicolosi’s death, the globular or Nicolosi projection replaced the stereographic projection popularized by Mercator, which had increasingly fallen into disuse. During the 19th century, the Nicolosi perspective became the standard cartographic projection technique, and it remains in use today.

Map details

The late 16th-century Italian schools of cartography are often credited as a significant source of inspiration for Nicolosi. As mentioned above, another primary source of inspiration came from the great French cartographer Nicolas Sanson, who had published a similar hemispherical map of the world in 1651 (and another in 1652) to great acclaim. The inspiration drawn from Sanson is manifested in the overall expression and form of Nicolosi’s map and in the deliberate omission of any decorative embellishments. In his time, Sanson was often regarded as the father of a more precise and scientific school of cartography. Sanson was among the first significant cartographers to abandon pictorial decoration and embellishment to underscore this image. Nicolosi followed this school of thought, partly because he considered himself and his output as something approaching science.

Many of the map’s details have been directly adapted from Sanson, although Nicolosi also incorporates several new cartographic features and place names. The most famous alteration is that the Rio Grande (labeled Rio Escondido) is shown flowing southeast into the Gulf of Mexico, with an elaborate set of tributaries. This constitutes the first appearance of the proper course of the Rio Grande on a printed map, or, more accurately, “tied” for first alongside Nicolosi’s four-sheet chart of North America from the same atlas. The accurate depiction of the course of the Rio Grande from the area of Santa Fe into the Gulf of Mexico was a drastic departure from Sanson and other contemporary mapmakers, who mistakenly mapped a river flowing from a lake in the

opposite direction, emptying into the Gulf of California. The source of Nicolosi’s correction and inclusion remains a mystery. Still, it is probably a reflection of the kind of access to archives and materials he had as a Vatican scholar, which makes his world and North American maps of crucial importance to the cartographic history of the American West.

As with all 17th-century world maps, Nicolosi’s chart captures the European understanding of the world during an age in which it was undergoing rapid, almost daily, change. This is seen in the strange composition of the Pacific and its western archipelagos. A very tentative outline of New Zealand in the Western Hemisphere and a similarly vague Australia or New Holland, including Van Diemens Land (Tasmania) in the Eastern Hemisphere, reflects the pioneering Dutch ventures of Abel Tasman and Franchoijs Visscher to this region in 1642. Nicolosi is, in other words, incorporating territories discovered no more than a decade earlier by a competing nation hostile to the Catholic Church. Acquiring, assessing, and combining this material is another important new inclusion contrasting his otherwise conservative approach. It is, for example, not surprising to find Nicolosi depicting California as an island, as his maps were issued during the heyday of this trend, just as it is unsurprising that the entire western half of North America at this stage simply is labeled New Spain.

In the Northwest Pacific, we see clear manifestations of the ample mythology associated with mapmaking. The Jesso and Anian concepts are cartographic myths extensively explored and explained by scholarship. The etymology of the idiom Jesso is most likely the Japanese Ezo-chi, a term used for the lands north of the island of Honshu. During the Edō period (1600-1886), it came to represent the ‘foreigners’ on the Kuril and Sakhalin islands north of Japan. As European traders came into contact with the Japanese in the 17th century, the term was adopted and incorporated rather uncritically onto European maps, where it was often associated with the island of Hokkaido. Jesso’s importance is traced back to Father Francis Xavier (1506-1552), an early Jesuit missionary to Japan and China. Xavier related stories that immense silver mines were to be found on a secluded Japanese island, and these stories were soon strengthened by Spanish traders spreading similar reports. The rumors became so tenacious and widespread that Abraham Ortelius included an island of silver above Japan on his 1589 Maris Pacifici map. Half a century later, the powerful Dutch East India Company sponsored two voyages of exploration to identify and possibly claim these rich lands for Holland. Abel Tasman led the first in 1639 and the second by Maarten Gerritzoon Vries in 1643. Vries erroneously perceived Urup as America’s westernmost fringe, and mapmakers soon adopted this concept. Over time, variations occurred in this undefined land known as Jesso.

Anian, on the other hand, was often used in 17th-century maps as a term for the passage from the Arctic Sea and into the Pacific (known today as the Bering Strait). Cartographically, the Anian concept dates back to at least 1562, when it appeared on a map issued by Giacomo Castaldi. Still, during the 16th century, famous cartographers such as Ortelius, Zaltieri, and Mercator also used it in maps. The concept’s popularity in cartographic circles can probably be traced back to the late 16th century, when a Greek navigator, Ioánnis Phokás, supposedly was sent north from New Spain (twice, no less) in 1592. His goal was to find and map this mythical Strait of Anian. Following the American coastline for more than twenty days, he finally reached the northern cusp of the continent. His story was eventually published in Samuel Purchas’ travel collection in 1625, cementing the term for the next hundred years. Yet the concept’s origin is one thing; defining more precisely where and what it was was something altogether different. Consequently, from the early 17th century until the extensive survey of the Second Kamchatka expedition under the leadership of Vitus Bering (1733-43), the Strait of Anian was depicted in many ways on European maps. Nicolosi takes the somewhat progressive but widespread view at the time that Jesso was part of an Asian landmass or eastern archipelago and that Anian constituted the passage between that landmass and the new American continent.

Cartographer(s):

Giovanni Battista Nicolosi (1610-1670), also known as Giovan Battista, was a Sicilian priest, geographer, and cartographer who worked for the Vatican’s Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples (or Propaganda Fide) under Pope Gregory XV. Officially, the Fide office was established to promote missionary work across the globe. Still, the reality was that it constituted an essential office for the maintenance and dilation of the Church’s power in an ever-expanding world.

Arriving in the papal capital around 1640, Nicolosi studied letters, sciences, geography, and languages. In 1642, he published his Theory of the Terrestrial Globe, a small treatise on mathematical geography, and a few years later, his guide to geographic study was issued, a short treatise on cosmography and cartography. Both works reflected a Ptolemaic worldview, but his guide to geographic analysis would soon serve as an introduction to Nicolosi’s real magnum opus, Dell’ Ercole e Studio Geografico, first published in 1660. On the other hand, his Theory of the Terrestrial Globe brought Nicolosi to the attention of broader scientific circles. It earned him the Chair of Geography at the University of Rome. In late 1645, he traveled to Germany at the invitation of Ferdinand Maximilian of Baden-Baden, where he remained for several years until he returned to Rome. Here, Nicolosi was appointed chaplain of the Borghesiana in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore. This honor was conferred on him by Prince Giovanni Battista Borghese, whom Nicolosi had tutored and in whose palace he had lived since 1651. Years later, Nicolosi would thank the prince for his generosity by dedicating his most seminal work to him.

A considerable collection of Nicolosi’s unpublished work exists in the Vatican and other national archives. This includes a large chorographic (i.e. descriptive) map of all of Christendom, commissioned by Pope Alexander VII, and a full geographic description and map of the Kingdom of Naples, which was sent to Habsburg Emperor Leopold I in 1654.

Condition Description

Very good, mild toning and some soiling in the margins. 2 sheets unjoined (can be joined on request).

References