Sebastian Münster’s Seminal Map of Asia.

Die Länder Asie nach ihrer Gelegenheiten bis in Indien werden in dieser Tafel verzeichnet.

$1,600

1 in stock

Description

An Early Manifestation of the Transition from Ptolemaic Geography to Modern Cartography.

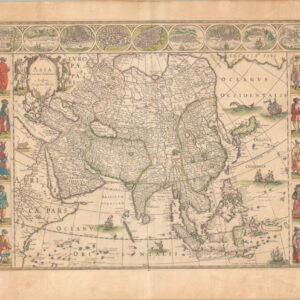

Sebastian Münster’s map of Asia is one of the first printed maps to challenge traditional Ptolemaic conceptions of the continent’s geography. The large East Asian peninsula, often referred to as the “Dragon Tail”, which appears in maps such as Laurent Fries’ 1535 world map, is notably absent. Instead, Münster makes an early attempt to merge Classical geographic ideas with contemporary observations from travelers, merchants, and explorers. This map covers the entire Asian landmass, including the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific.

At first glance, the map might appear simplistic, adhering to the schematic representation of space common in 15th- and early 16th-century cartography. The map stretches from Moscow in the west to the coast of Cathay (China) in the east, and from the Arctic Ocean (Oceanus Hyperboreus) in the north to the Indian Subcontinent and the Indonesian Archipelago in the south. Across the continent, Münster includes stylized mountain ranges, rivers, and lakes, as well as quadratic depictions of the Caspian Sea and Persian Gulf, features characteristic of the Ptolemaic tradition.

Despite the vast expanse the map covers, relatively few place names are included, a reflection of Europe’s limited knowledge of Asia at the time. Some recognizable toponyms include India, Cathay, Parthia, and Arabia. Münster also marks several key trade ports, both indigenous settlements (e.g., Aden and Khambhat) and colonial outposts (e.g., Goa).

Geographic Curiosities and Cartographic Innovations

The map contains both misplaced toponyms and groundbreaking new ideas. A notable example is Münster’s labeling of what is now Chukotka (northeastern Russia) as “India Superior”. This curious misidentification is not entirely arbitrary—it reflects early European speculation about the existence of a Northwest Passage to India. Such geographic errors highlight the ambitions behind Münster’s cartography, as he attempted to reconcile theoretical geography with emerging knowledge from explorers.

Other peculiarities include the division of Java into two islands, labeled Java Maior and Java Minor, as well as the misplacement of Zanzibar, which appears southeast of Madagascar in the southern Indian Ocean.

Münster also breaks new ground in his depiction of the Pacific Ocean, which he describes as a vast archipelago containing 7,448 islands surrounding Japan. The original version of this map was produced around 1540, several years before the first European ships reached Japan. Münster based his knowledge on 14th-century reports from Marco Polo, demonstrating how pre-modern cartography often relied on much older sources.

The Role of Münster’s Map in the Cosmographia

One might ask why Japan is even referenced when it does not appear on this map. This anomaly underscores Münster’s revisionist approach to world geography. While he remained deeply influenced by the Ptolemaic worldview, he was also keen to incorporate first-hand reports from explorers. This led to his unique strategy of linking maps together.

When this Asia map is placed alongside Münster’s America map from the same edition of Cosmographia, they collectively form one of the first printed maps of the Pacific Ocean in its entirety. This also resolves the Japan omission, as Münster pushed its location so far west that it appears on his America map instead.

Sea Creatures and Decorative Elements

A hallmark of 16th-century cartography was the inclusion of mythological and exaggerated creatures, reflecting both fear of the unknown and European artistic traditions. At the bottom of Münster’s map, a large sea monster can be seen, a common feature in his works.

A particularly rare and enigmatic figure appears in the lower right corner—an ichthyocentaur (a half-human, half-sea creature). While similar figures appear in later maps, such as Ortelius’ 1590 map of Iceland, Münster’s version predates these by nearly three decades. Unlike the bearded men of Greek mythology, Münster’s ichthyocentaur is depicted as a child-like figure with a double tail, making this an exceptionally early representation of the creature.

Context Is Everything

The original version of this map was first published by Münster in 1540, as part of his updated edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia. With the discovery of the New World in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, mapmakers were faced with the challenge of integrating new geographic knowledge into their work. This task required access to explorers’ reports, manuscript maps, and other restricted information, much of which was closely guarded by European governments, universities, and trading companies.

Münster was one of the few cartographers with privileged access to such information. As one of the leading figures in the “New Cartography” movement, he not only revised classical maps but also introduced entirely new ones, such as his pioneering charts of Asia and the Americas.

As Münster’s reputation as a cartographer grew, so did his drive for innovation. He understood that in an era of rapidly expanding geographic knowledge, it was essential to bridge the gap between ancient models and modern discoveries. This is why he included new maps when he published Cosmographia in 1544. The work quickly became one of the most popular atlases of the 16th century, going through more than forty editions over the next century. As such, Münster’s Cosmographia became the first truly influential world atlas published in Germany.

Cartographer(s):

Sebastian Münster (1488-1552) was a cosmographer and professor of Hebrew who taught at Tübingen, Heidelberg, and Basel. He settled in Basel in 1529 and died there, of the plague, in 1552. Münster was a networking specialist and stood at the center of a large network of scholars from whom he obtained geographic descriptions, maps, and directions.

As a young man, Münster joined the Franciscan order, in which he became a priest. He studied geography at Tübingen, graduating in 1518. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Basel for the first time, where he published a Hebrew grammar, one of the first books in Hebrew published in Germany. In 1521, Münster moved to Heidelberg, where he continued to publish Hebrew texts and the first German books in Aramaic. After converting to Protestantism in 1529, he took over the chair of Hebrew at Basel, where he published his main Hebrew work, a two-volume Old Testament with a Latin translation.

Münster published his first known map, a map of Germany, in 1525. Three years later, he released a treatise on sundials. But it would not be until 1540 that he published his first cartographic tour de force: the Geographia universalis vetus et nova, an updated edition of Ptolemy’s Geography. In addition to the Ptolemaic maps, Münster added 21 modern maps. Among Münster’s innovations was the inclusion of map for each continent, a concept that would influence Abraham Ortelius and other early atlas makers in the decades to come. The Geographia was reprinted in 1542, 1545, and 1552.

Münster’s masterpiece was nevertheless his Cosmographia universalis. First published in 1544, the book was reissued in at least 35 editions by 1628. It was the first German-language description of the world and contained 471 woodcuts and 26 maps over six volumes. The Cosmographia was widely used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and many of its maps were adopted and modified over time, making Münster an influential cornerstone of geographical thought for generations.

Condition Description

Hand color. Visible repairs, as seen on the image. Overall nice.

References