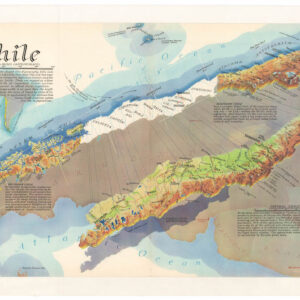

Argentinian propaganda map of Chile’s advance into Patagonia.

[Persuasive Cartography] La Cuestión Chilena.

$975

1 in stock

Description

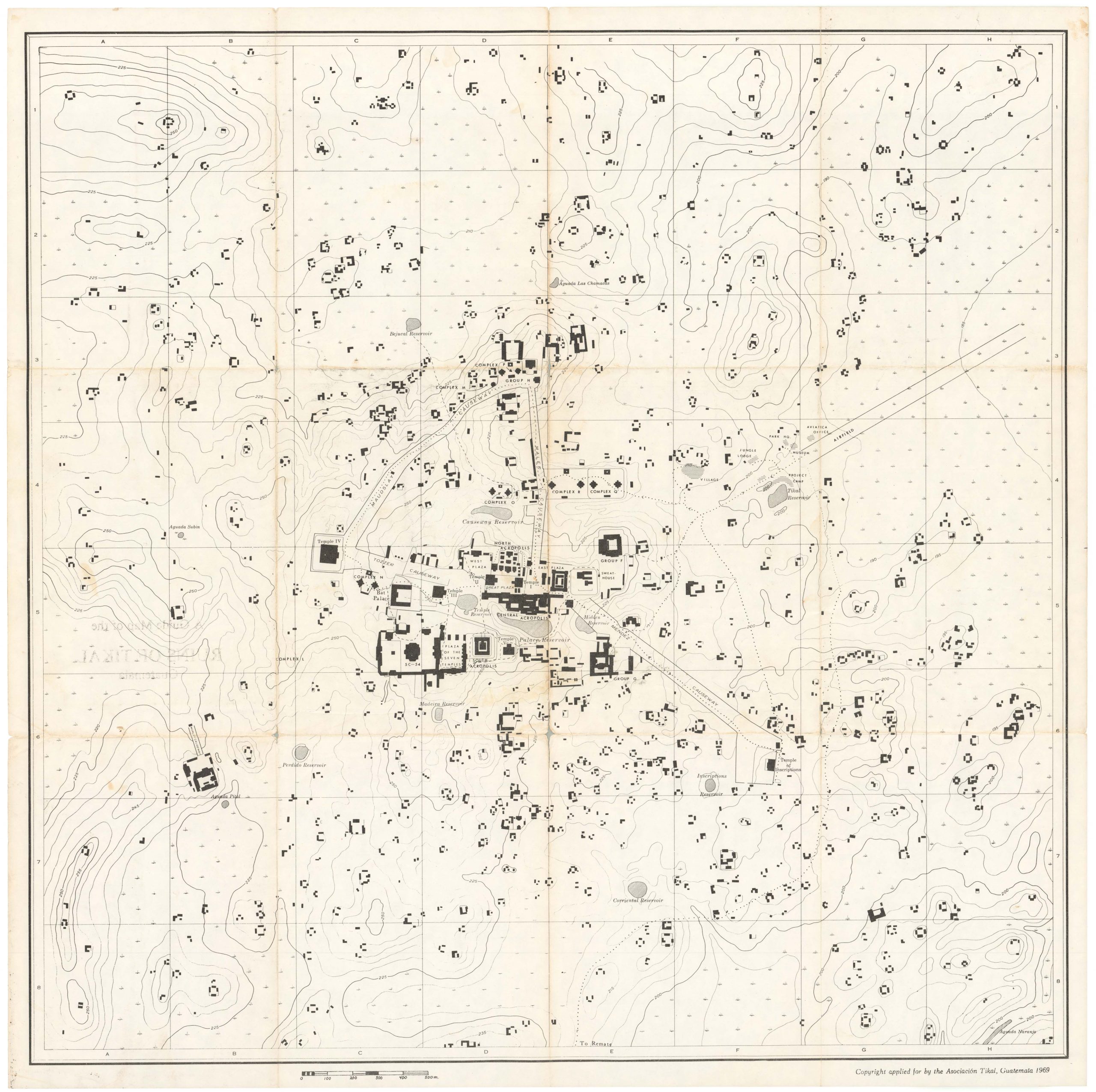

This is an anonymous and undated propaganda map, prepared by Argentina’s Foreign Ministry for dissemination among potential allies on the American continents. It regards the conflict known as the “East Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego and Strait of Magellan dispute” or “Patagonia Question,” which was a territorial dispute between Chile and Argentina during most of the 19th century (for more context, see section below).

The sheet centers on five maps, which are distinguished only by the varying size of the swathe of red that is meant to outline Chile’s encroachment into Argentine Patagonia. The expansion process began in 1843 with only a few small islands and tiny peninsulas in the western part of the Strait of Magellan, but by 1847, Chile was claiming the entire Strait as its own. The expansion continues in three subsequent phases, each documented with its own map, until 1876, when the territory in dispute consists of virtually all of Patagonia, or the southern half of Argentina. Each of the intermediary stages in the quintet of displayed maps is dated, and the territories in question are highlighted in red. Under each phase are noted the year(s) in question, as well as a brief explanation of the particulars of each phase of the expansion—all of it from an Argentine perspective, of course.

The Argentinian Foreign Ministry designed the map as a means of visualizing what Argentina considered the ongoing encroachment by Chile on Argentine territory. The broadsheet highlighted the blatant nature of Chilean territorial claims.

Because of this background and purpose, the sheet was only distributed in limited circles, making it a rarity today. The only institutional example of this map in the United States was presented to the US Minister to Argentina, Thomas Ogden Osborn, by the Argentine Minister of Foreign Affairs, to serve precisely the purpose for which it was designed. The United States did indeed get involved and played a key role in the ensuing treaty negotiations (1879-1881).

Census

This sheet is rare, likely because it was never produced in large quantities to begin with. There is only a single example of this sheet in US institutions. This document is located in the National Archives (NAID: 5675669) and is the same sheet that Thomas Ogden Osborn sent to US Secretary of State William M. Evarts in 1880, following his role as US mediator in the negotiations for the 1881 Boundary Treaty that ended the conflict.

The only other institutional example we have been able to identify is held in the Biblioteca Nacional de España (OCLC no. 431564806).

Context is Everything

The Strait of Magellan dispute and the “Patagonia Question” (1842–1881)

The “Patagonia Question” was a nineteenth-century sovereignty dispute between Chile and Argentina over the southernmost lands of South America (i.e. East Patagonia, the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego and the strategically vital Strait of Magellan). Its roots lay in the messy inheritance of Spanish colonial jurisdictions and centuries of imprecise royal decrees that left overlapping claims along the entire Andean-to-Atlantic sweep. Both countries gradually sought to translate old legal claims into an effective national occupation: Chile concentrated on the Pacific channels and the Strait. At the same time, Argentina pushed settlement eastward across the pampas and into Chubut.

Tensions hardened during the mid-1800s. Chile’s deliberate occupation of the Strait of Magellan, symbolized by the 1843 expedition that founded Fuerte Bulnes and formally took possession of the strait, alarmed Buenos Aires and was the source of repeated diplomatic protests. Argentina, in turn, fostered new settlements, established informal alliances with indigenous leaders, and ensured a significant naval presence to assert influence on the Atlantic coast. By the 1870s, both states were populating adjacent zones and commissioning maps and legal arguments to buttress their claims. This map is one such example from the Argentine side.

The trigger for a negotiated containment and ultimately a resolution of the conflict came in December 1878, when Chile and Argentina signed the Fierro–Sarratea agreement. This was an interim pact that postponed a final delimitation and established arbitration procedures to avoid a fully fledged armed conflict. Chile quickly ratified the agreement, but Argentina’s Congress never gave its final approval, causing it to collapse as a comprehensive settlement. The outbreak of the War of the Pacific (1879–1884), in which Chile fought Peru and Bolivia, made rapid de-escalation with Argentina diplomatically urgent. Chile wished to avoid a second front. At the same time, Argentina was engaged in the “Conquest of the Desert” on its southern frontier, pushing it to resolve this old conflict as well.

The crisis was finally resolved by the Boundary Treaty of 23 July 1881. The treaty adopted a practical formula: north to the 52°S parallel the boundary would follow the highest Andes watershed; south of 52°S the agreement recognized Chilean sovereignty over the Strait of Magellan and assigned islands and Tierra del Fuego between the two states according to specified meridians and channels. Crucially, the treaty neutralized the Strait of Magellan and guaranteed free navigation to all nations; a provision that allowed international passage through the strait and prevented any single power from controlling it.

US involvement in the dispute was modest. Washington did not act as an official guarantor or principal mediator in the 1881 settlement. However, diplomatic records and dispatches confirm that the situation was under close observation, and US diplomats regularly reported to their superiors on the crisis’s development and its regional implications (especially for shipping routes). Formal third-party arbitration and boundary adjudications were carried out by various state actors (notably Britain) or by various bilateral protocols. In short, the U.S. was an interested observer rather than a decisive actor in both the dispute and its resolution.

The conflict illustrates how colonial legal ambiguities, competing settlement policies, and the strategic value of a single waterway combined to produce a long, fraught boundary contest. The 1881 Boundary Treaty, negotiated under the shadow of other regional wars and mediated by pragmatism rather than legality, integrated competing claims into a workable frontier and ensured the neutrality of the Strait of Magellan for international shipping.

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Good. Wear and toning along fold lines.

References