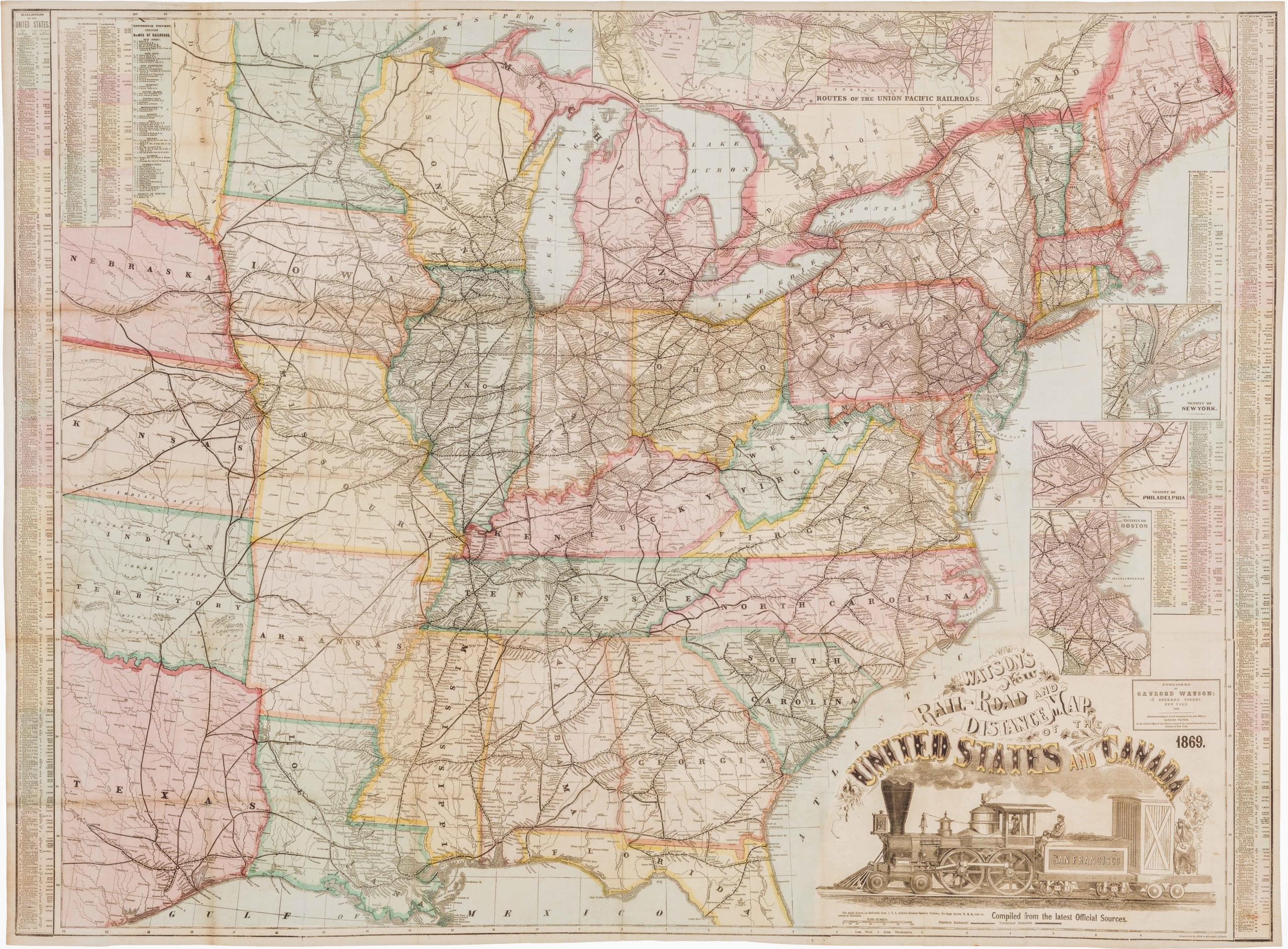

First edition of Haasis & Lubrecht’s iconic Transcontinental Railroad map.

The American Union Railroad Map Of The United States, British Possessions, West Indies, Mexico, And Central America. 1871. Published by Haasis & Lubrecht, 107 Liberty Street, New York. Smith & McDougal, Electrotypers, 82 Beekman Street, New York.

Out of stock

Description

This rare and highly decorative map of the United States is, in many ways, one of the earliest cartographic renditions of modern America. It represents a re-unified America, in which most of the states and territories have been formally organized and connected by railroads.

This striking map of the United States celebrates one of the nation’s most significant infrastructure projects: the Transcontinental Railroad. This massive national endeavor was deemed of the highest priority and importance in the late 1860s, primarily because it connected the vast new territories in the West to the old colonies on the East Coast and opened new pathways for mobility, communication, and, especially, trade. The map was issued just over a year after the official completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. On May 10th, 1869, the presidents of two competing railroad companies met at Promontory Summit, Utah, to jointly drive in the last spike of a line that connected their two railways.

The completion the Transcontinental Railroad was a great symbolic victory. In the decade preceding the publication of this map, the United States had been ripped apart by the Civil War. Now, for the first time in history, it was possible to traverse North America without having to take the arduous and often dangerous journey by wagon trail. The completion of a transcontinental railway thus stimulated what would later be known as ‘Railroad Fever,’ with large numbers of people traveling west, either to visit or to relocate. Consequently, and despite its symbolic importance in a nation still healing from the great rift of the Civil War, this map is primarily a functional chart: a tool for those intending to undertake a cross-country voyage. The map contains a wealth of valuable information for the railroad traveller, including an elegant circular ‘time and distance table’ in the lower-left corner. This informs the traveller of both the time and distance required for a particular journey from the nation’s capital.

This fabulous wheel of clocks highlights the vital role railroads played in the standardization of time in the United States. With its journey across multiple time zones, the Transcontinental Railroad, in particular, helped to formalize how time was to be commonly understood and used in America. Twelve years after the publication of this map, in October 1883, delegates from all the railroad companies met with government officials in Chicago, in what has since come to be known as the General Time Convention. Here, the Standard Time System was adopted and put into effect already the following month. It was a monumental logistical task and remains the system by which U.S. time zones are subdivided to this day. The general spirit of the age, and especially the importance of this particular advancement, is perhaps best captured by an article in the November 21st, 1883 edition of the Indianapolis Sentinel:

“Railroad time is the time of the future. The Sun is no longer to boss the job. People— all 55,000,000 of them — must eat, sleep, and work as well as travel by railroad time. It is a revolt, a rebellion. The sun will be requested to rise and set by railroad time. The planets must, in the future, make their circuits by such timetables as railroad magnates arrange. People will have to marry by railroad time and die by railroad time. Ministers will be required to preach by railroad time—banks will open and close by railroad time—in fact, the Railroad Convention has taken charge of the time business, and the people may as well set about adjusting their affairs in accordance with its decree…. We presume the sun, moon, and stars will attempt to ignore the orders of the Railroad Convention, but they, too, will have to give in at last.”

Equally telling of the atmosphere in which this map was compiled, we find extensive tables of population statistics from the 1870 census, here broken down into first states and then counties. These tables provided potential settlers with an idea of population density in regions undergoing constant growth and development. This was the most up-to-date demographic data for a nation in constant flux. It is worth noting that later editions of this map, issued in 1872 and 1873, also included short descriptive texts for each state or territory next to its census figures. The lack of these descriptions on our map confirms that it is the original 1871 edition.

The map also includes several insets, each revealing in its own way. As indicated in the map’s title, the chart covers not only the United States but also the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America. The latter is represented by a small inset in the lower left of the map, underscoring how this region was still being shaped to become the multinational isthmus we know today. Thus we find the relatively new nations of Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, San Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica all independently delineated and acknowledged. All of these small nations had declared independence from Mexico following the 1823 revolution that ousted Emperor Augustin de Iturbide. New legislation had allowed the Central American provinces to decide their own fate regarding national affiliation, and all chose independence.

At the top of the sheet, we find one of two pictorial scenes on the map. Aptly titled ‘From the Atlantic to the Pacific,’ this brightly colored image provides a panoramic view that sweeps from the densely inhabited Atlantic coast (represented by New York) to the bays of the Pacific (represented by San Francisco). In the heart of the country, we see several natural and man-made features, including America’s two greatest natural landmarks: the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. Running through the entire scene is, of course, the railroad, with multiple sets of locomotives drawing passenger wagons. Of the three visible sets of trains, two are heading west, while the third is climbing across California and Nevada, gradually approaching the previously in-traversable barrier of the Rockies.

The second pictorial scene, paired with the map’s title, depicts a classic railway station scene that could be in any provincial town in America. On the platform, prospective passengers say their goodbyes and board carrier-wagons, fronted by a steaming locomotive. Luggage and other goods are being accumulated on the platform by railway employees, waiting to be loaded on the train, and on the bridge above the tracks, we see a couple in a horse-drawn carriage, as if to underline the juxtaposition of the old world with the new.

While only the Transcontinental line had been completed when it was issued, it was only a matter of time before new, complementary cross-country railways were finalized. Many of these projected lines — particularly in the West — have been included on the map to ensure future relevance and to indicate how extensive the growing railroad network would become. Indeed, by the time the 1872 and 1873 editions were published, some of the projected stretches on the 1871 map were already operational. At the same time, these new editions saw the latest plans and projections added as prospective railway lines.

Census and rarity

Despite being issued in several editions, Haasis & Lubrecht’s railroad map was designed for use, not archival or display purposes. Consequently, most of these maps did not survive, and copies — especially of the original 1871 state — have become extremely rare. Map scholar and collector David Rumsey has stressed how the map was initially issued with German immigrants in mind. Both Haasis and Lubrecht had German roots and wanted to create a chart to help their fellow countrymen find their new home. Consequently, the maps were marketed to German immigrants, with later editions being sold in a marbled folding case with a label that read: “Der Amerikanische Continent. Nuesten topographische und Eisenbahn-Karte Vereinigten Staaten, Britischen Besitzungen, Westindien, Mexico & Central-America. Aus der Artistischen Anstalt von Haasis & Lubrecht in New-York. Stuttgart. Im Debit Bei Wilhelm Lubrecht, Jun. 1873.”

OCLC locates only two examples of this 1871 edition (University of Southern California and Colorado School of Mines). Rumsey notes editions of 1872 and 1874 and also identifies the Warren Heckrotte Copy of the 1873 edition.

Context is everything

Haasis & Lubrecht’s map is essentially a reworking of Lubrecht and Rosa’s “The American Continent” (1864). But so much had happened in the ensuing years that it was comprehensively modified and enhanced, constituting a new edition in a much more impressive format. In the 1864 map — which was still years away from seeing any transcontinental connection completed — a range of post-Civil War statistics had been included, but these data were now not only irrelevant, they were completely unaligned with the new ambitions that this map manifested. Consequently, these were replaced by the dramatic full-country panorama discussed above. A similar optimism is evident in the coloring of Haasis & Lubrecht’s map, and in the design of the elaborate title cartouche.

The idea of one or more transcontinental railroads was well-established before the Civil War. But it was as if, with the war, the need — both on a practical and symbolic level — had been beset with a new urgency. American entrepreneurs quickly heeded this call, visualizing the ensuing fortunes it would bring. After the Civil War, government support for a transcontinental railroad dramatically increased, and incentives in the form of subsidies and mortgage bonds, as well as potentially massive land claims, were highly enticing to railroad companies.

Private firms built on public land made available through extensive land grants. From California, companies based in Oakland and San Francisco began entertaining their own expansion plans. They began planning how to join the race by meeting their eastern counterparts somewhere in the middle. The first formal commission in this regard was the construction of 132 miles of rail between Oakland and Sacramento. From here, the Central Pacific Railway Company of California took over and constructed the almost 700 miles of track from Sacramento to Promontory Summit in Utah, where it linked up to the Union Pacific Railroad’s 1085-mile stretch from Council Bluffs in Iowa. By formally linking these two stretches on May 10th, 1869, the first transcontinental railway had become a reality. By year’s end, the final stretch of this network from Sacramento to San Francisco had also been completed. With this achievement, there was an immediate need for new maps to cover it. Large firms such as Colton responded efficiently, whereas other charts, such as the Haasis & Lubrecht map, appealed directly to specific user segments.

In the process of constructing railroads across America, it was not just fortunes that were made and lost, but entire cities and peoples that either were elevated or perished. The story of the railroads’ drive west is one of epic proportions, commemorated and retold in numerous forms. It is the story of a wondrous, almost superhuman achievement, populated by visionary (and sometimes infamous) characters such as Theodore Judah, Thomas Durant, and Leland Stanford, and laced with pertinent symbolism. Within a decade of the first connection, transcontinental railroads had become the backbone of America. Ultimately, the engine that drove America’s industrialization was the locomotive.

Cartographer(s):

Condition Description

Normal wear from use, else excellent. Original hand color.

References

OCLC locates only two examples of the 1871 edition (University of Southern California and Colorado School of Mines). Rumsey notes editions of 1871 and 1874 and also identifies the Warren Heckrotte Copy of the 1873 edition.